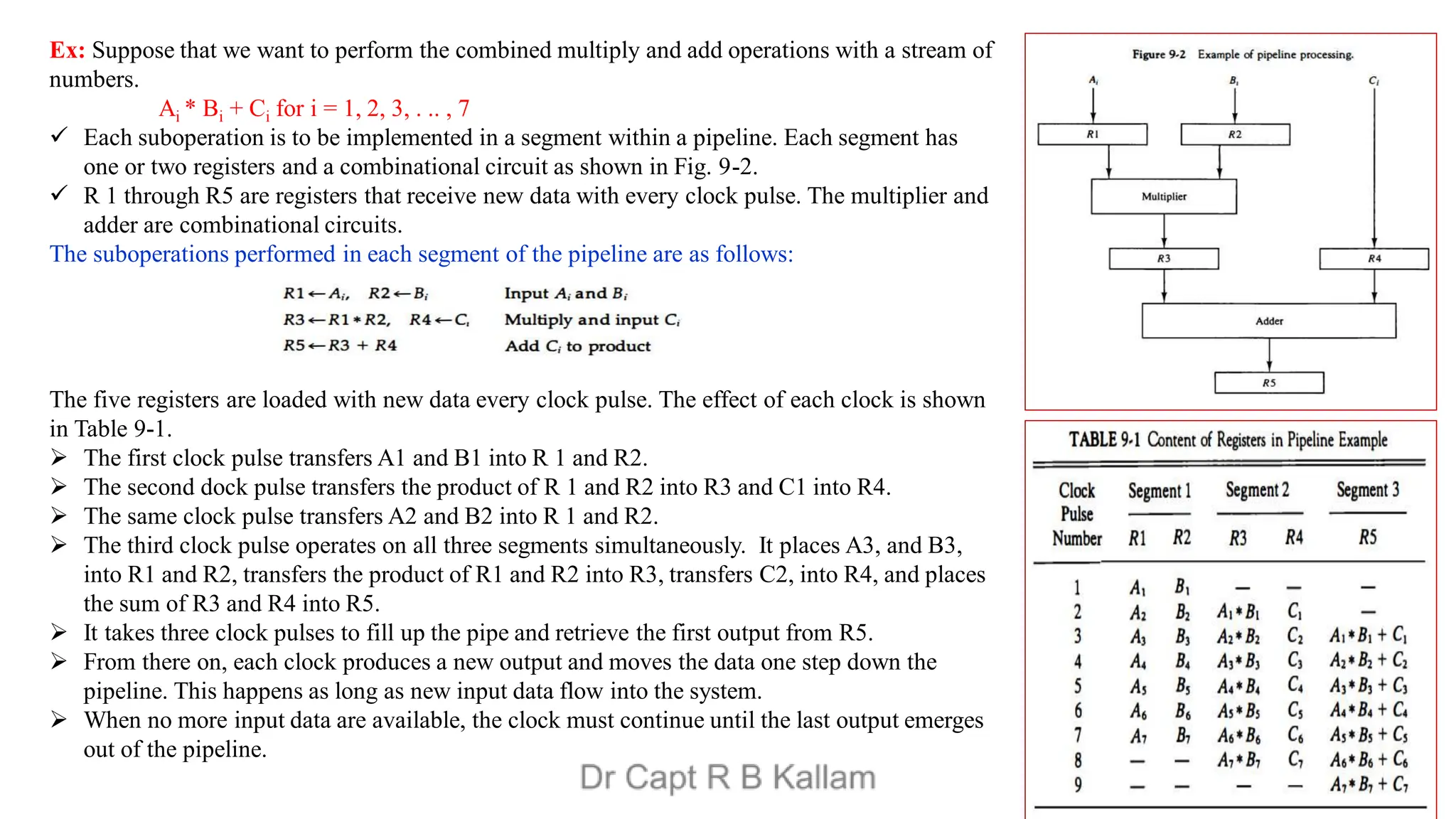

This document discusses the topics of computer organization and architecture, particularly focusing on concepts such as Reduced Instruction Set Computer (RISC) vs. Complex Instruction Set Computer (CISC), pipeline and vector processing, and various forms of parallel processing. It explains how instruction sets influence machine language programs, the advantages of RISC over CISC, and details different pipeline techniques including arithmetic and instruction pipelines, alongside challenges such as data dependencies and branch instruction handling. Additionally, it introduces Flynn's classification of computer architectures and outlines characteristics of multiprocessing systems.

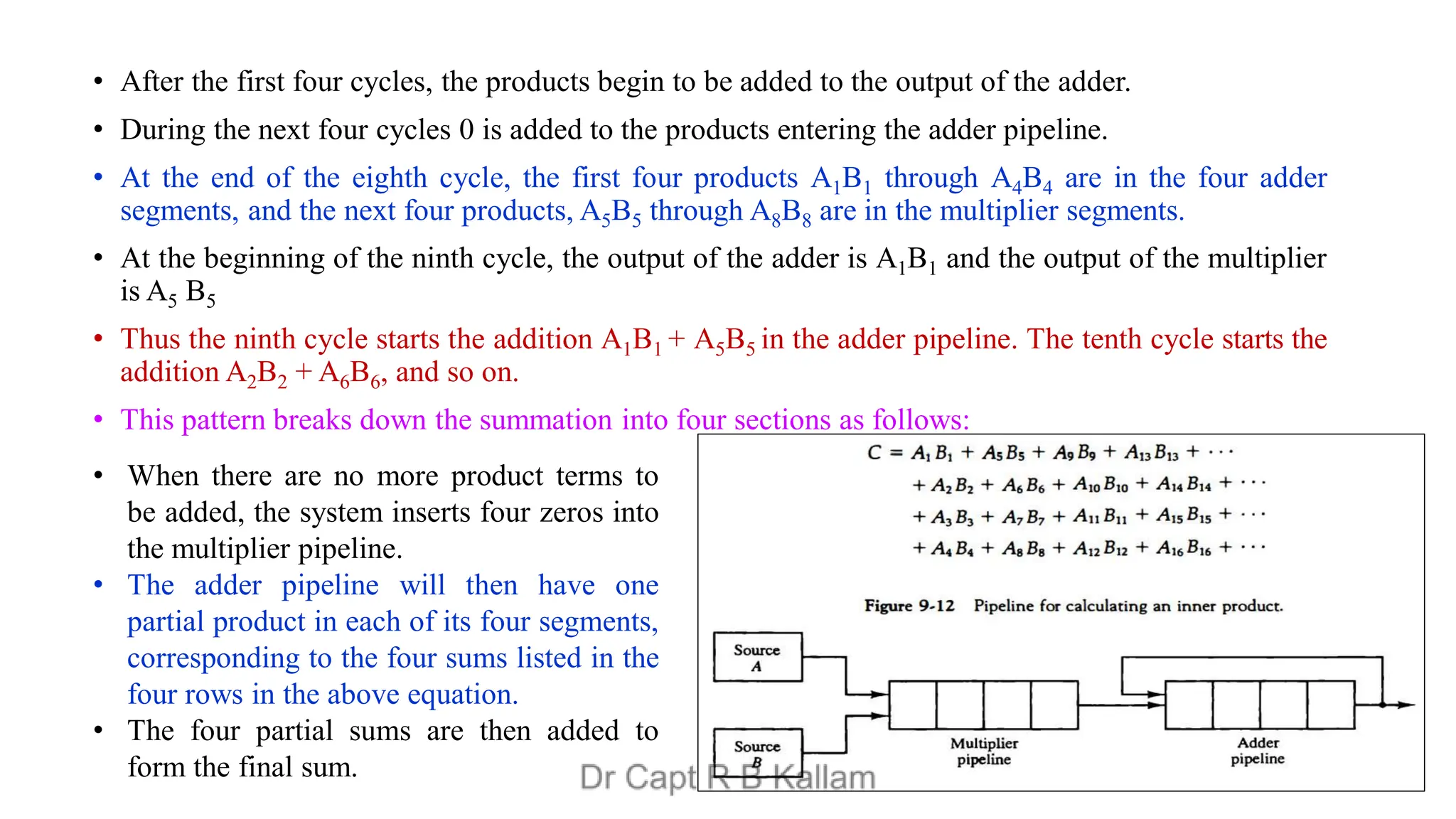

![Vector Processing

• A vector processor can process multiple data elements at once in parallel. These are more efficient and more complex

than the scalar processors.

• Application:

• Long-range weather forecasting

• Petroleum explorations

• Seismic data analysis

• Medical diagnosis

• Aerodynamics and space flight simulations

• Artificial intelligence and expert systems

• Mapping the human genome (DNA)

• Image processing

Vector Operations:

• Many scientific problems require arithmetic operations on large arrays of numbers. These numbers are usually

formulated as vectors and matrices.

• A vector is an ordered set of a one-dimensional array of data items.

• A vector V of length n is represented as a row vector by V = [V1, V2, V3, · · · Vn].

• It may be represented as a column vector if the data items are listed in a column.

• A conventional sequential computer is capable of processing operands one at a time. Consequently,

operations on vectors must be broken down into single computations with subscripted variables.

• The element Vi of vector V is written as V(I) and the index I refers to a memory address or register where

the number is stored.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/236unit5-coa-240825133653-5caa47eb/75/236UNIT5-COA-pdfvfrffccvnnnjuyyhgfeeesdd-28-2048.jpg)