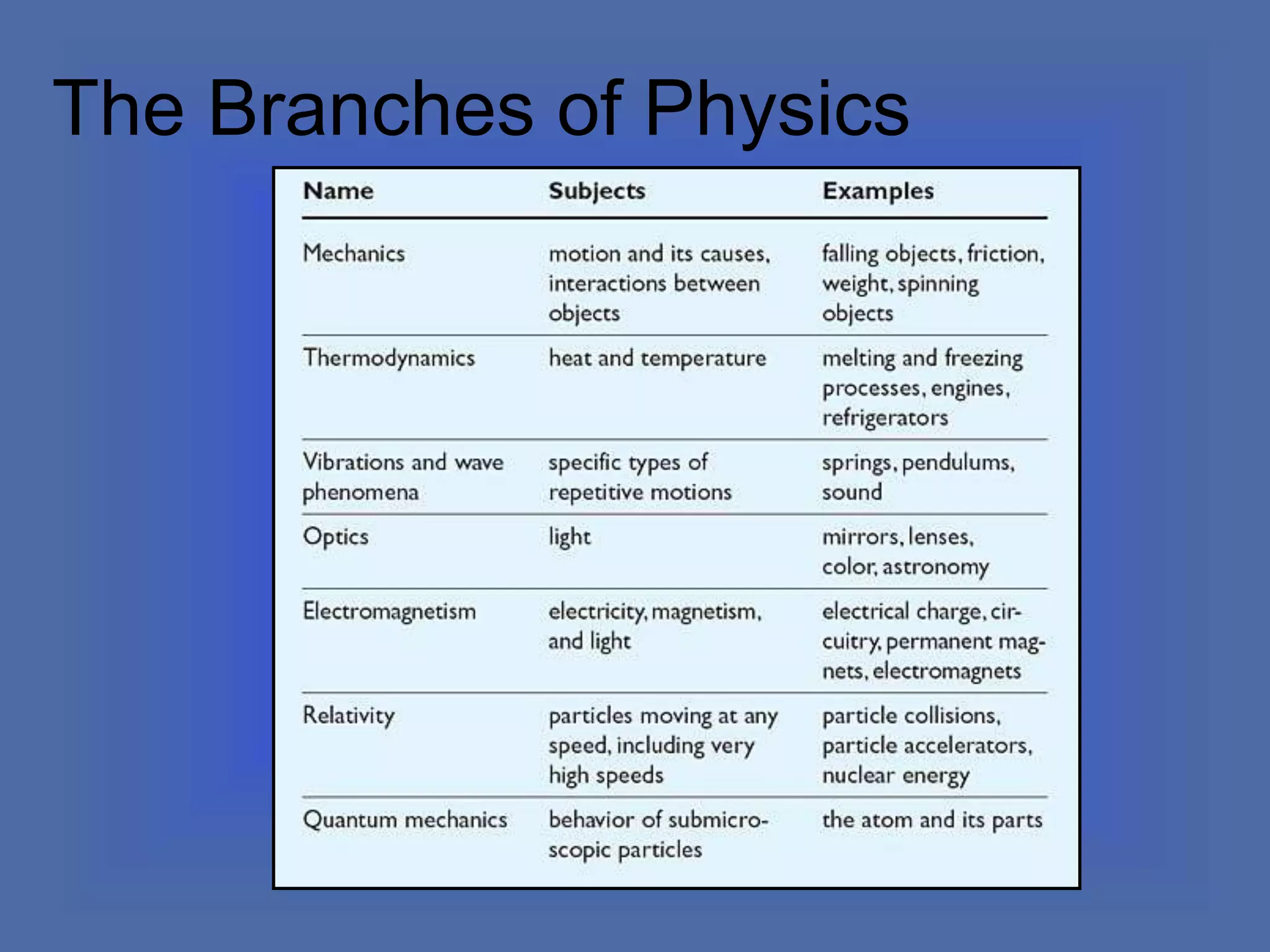

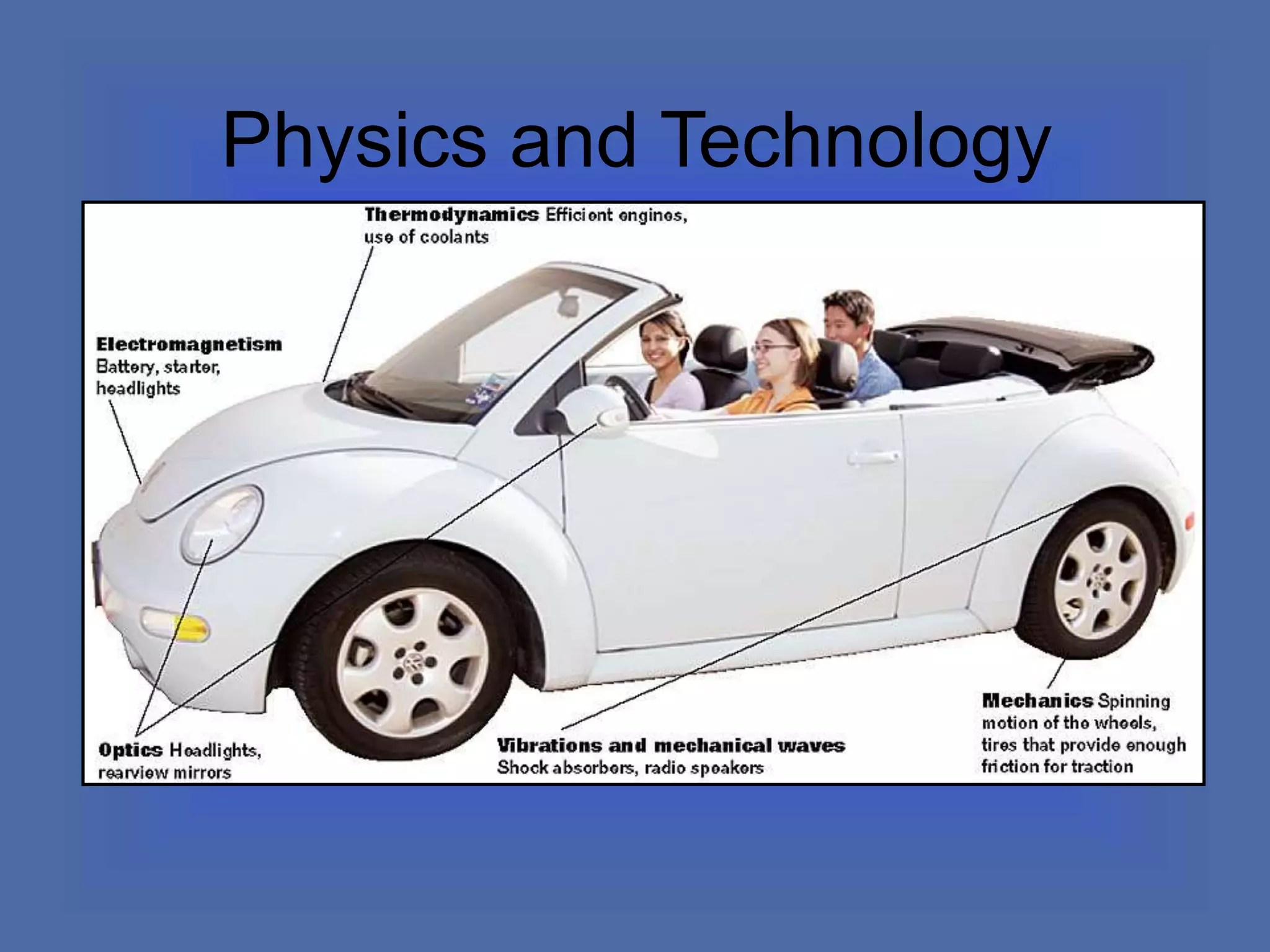

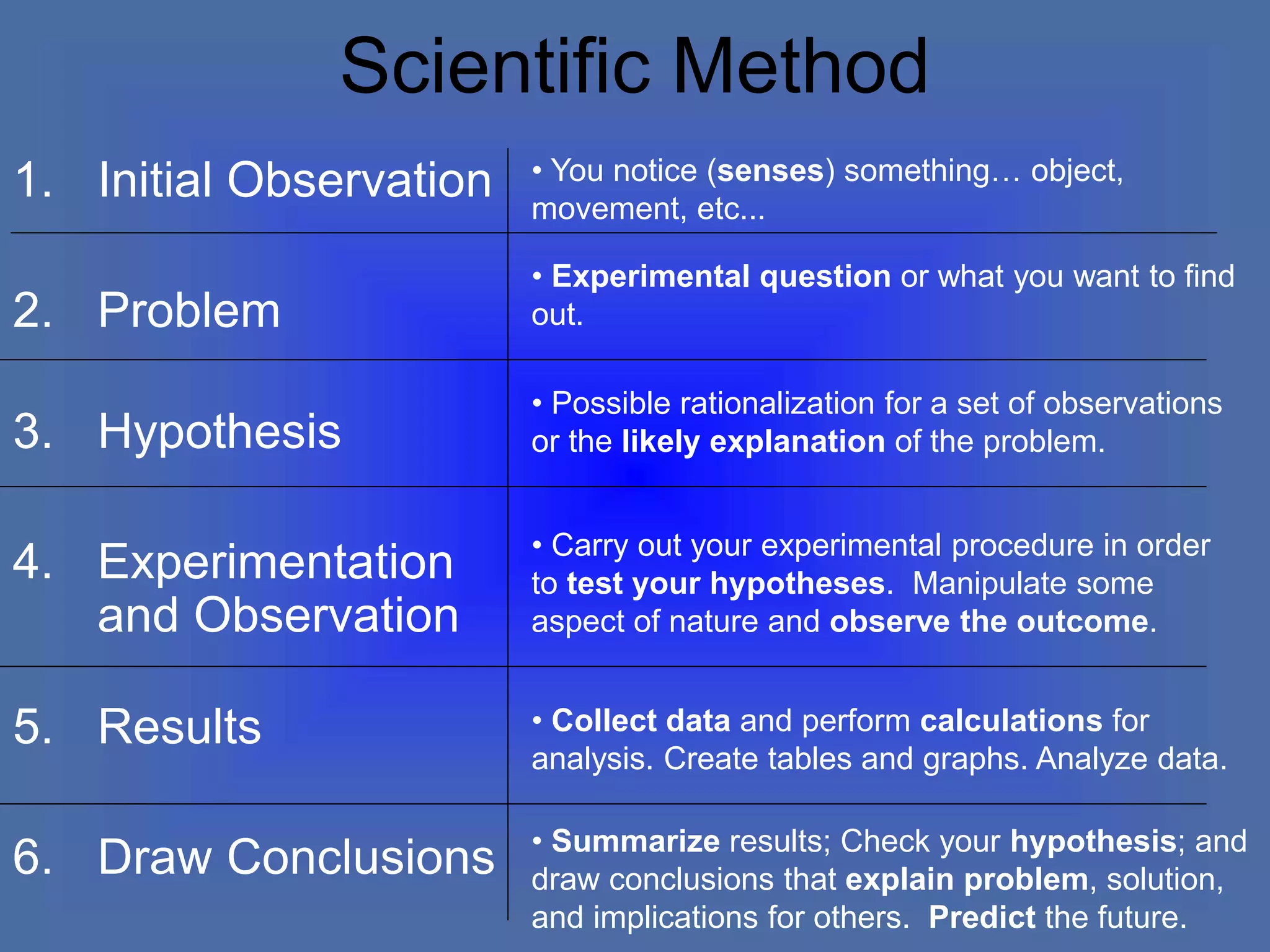

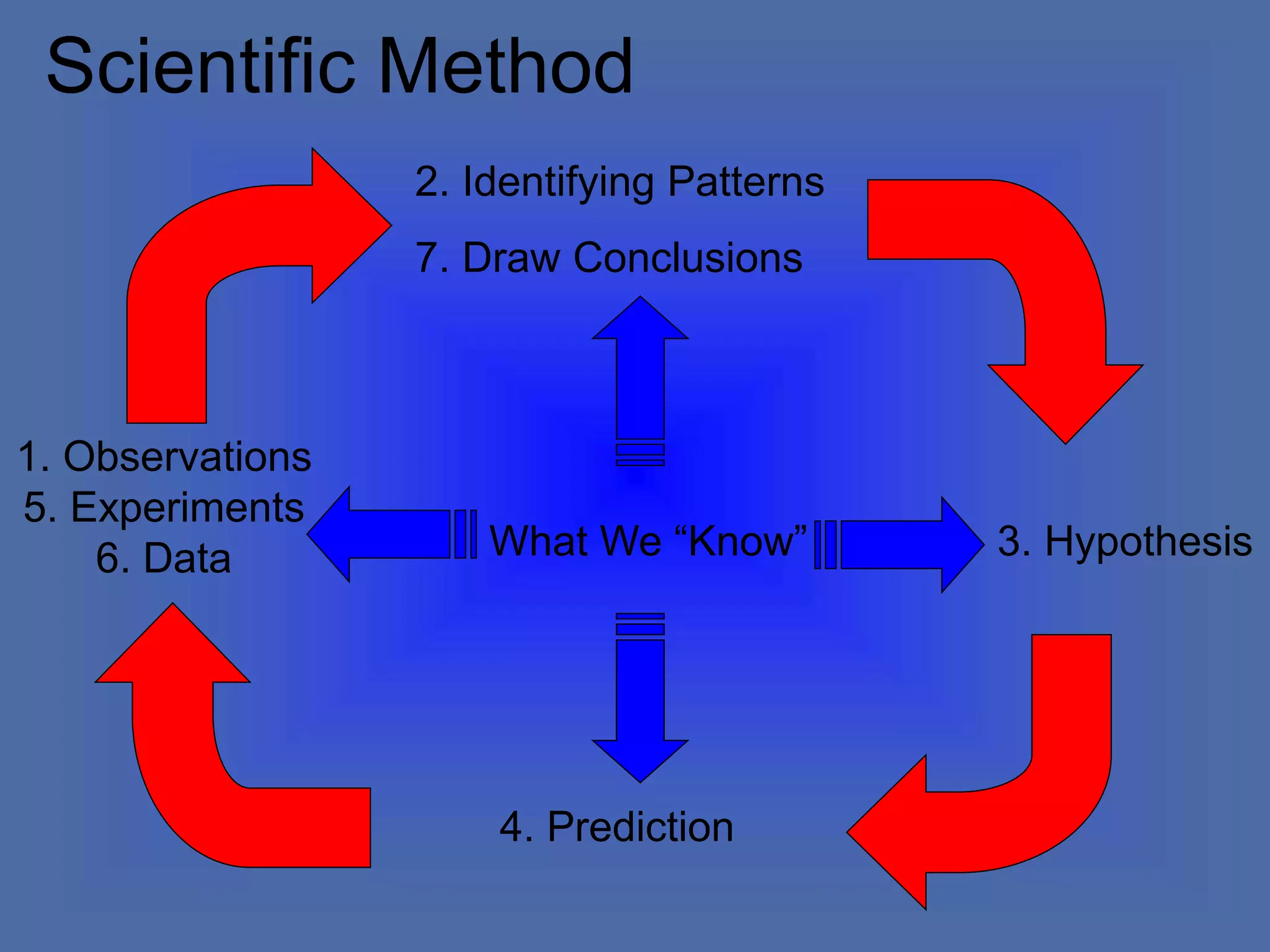

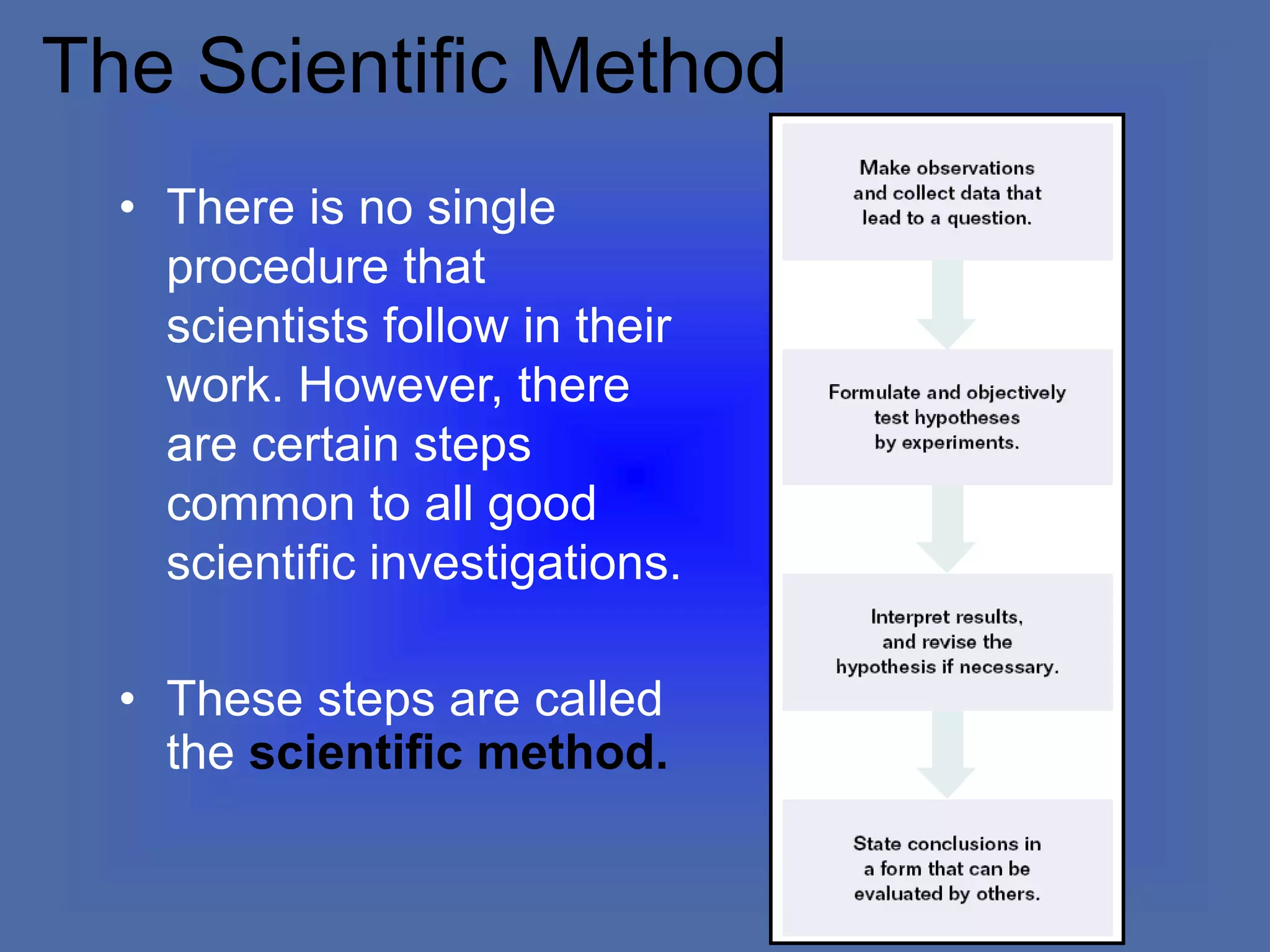

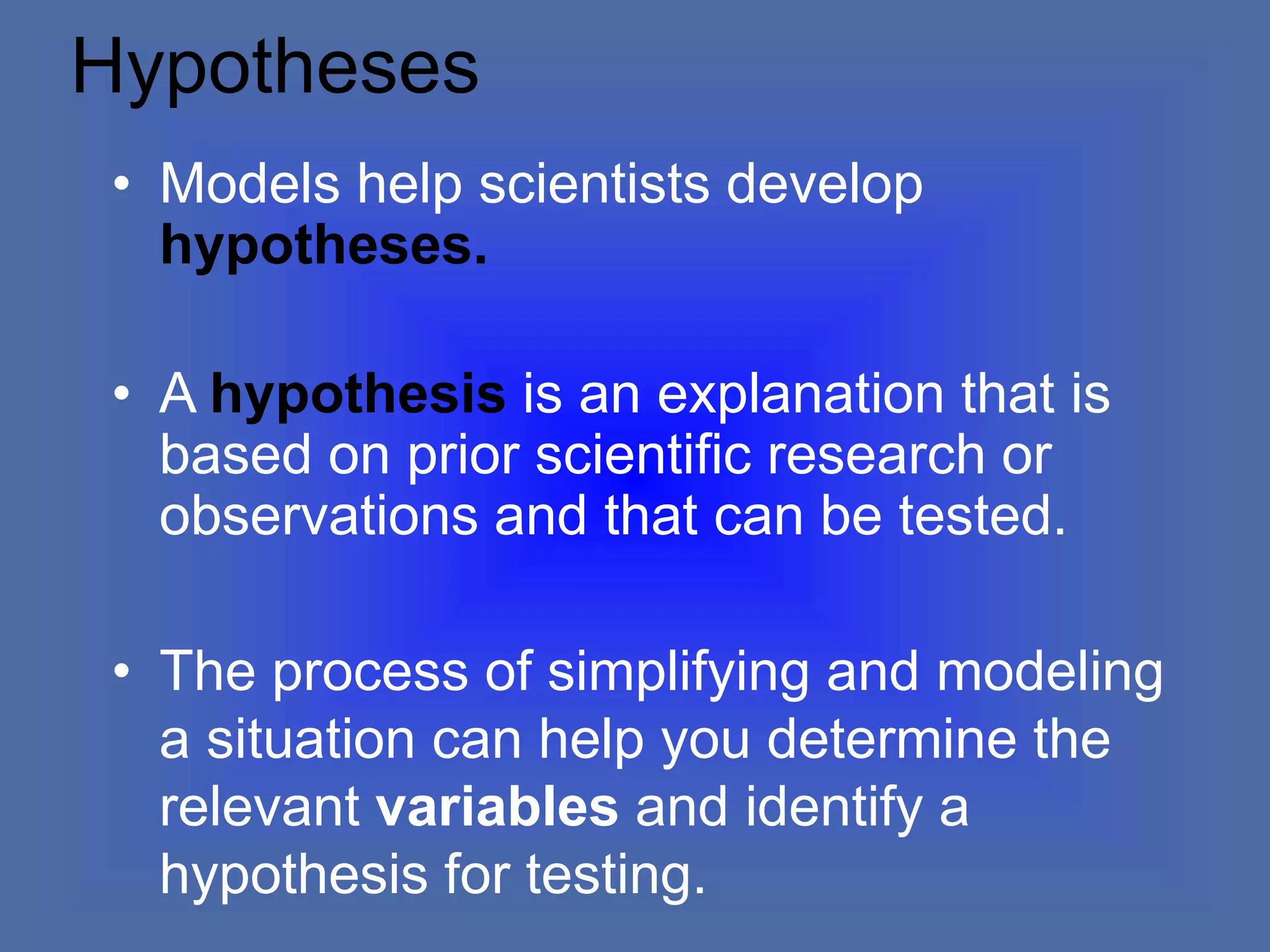

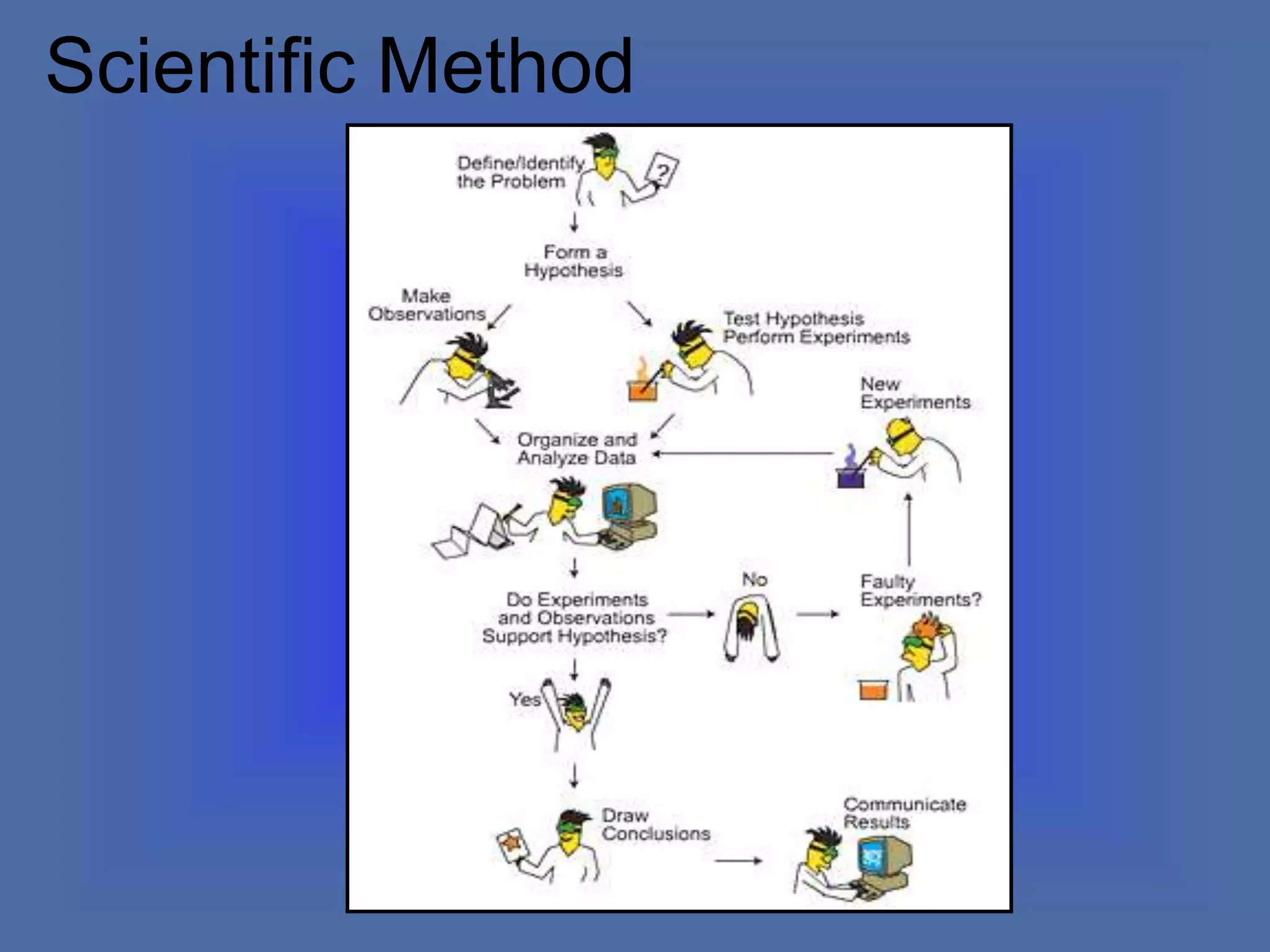

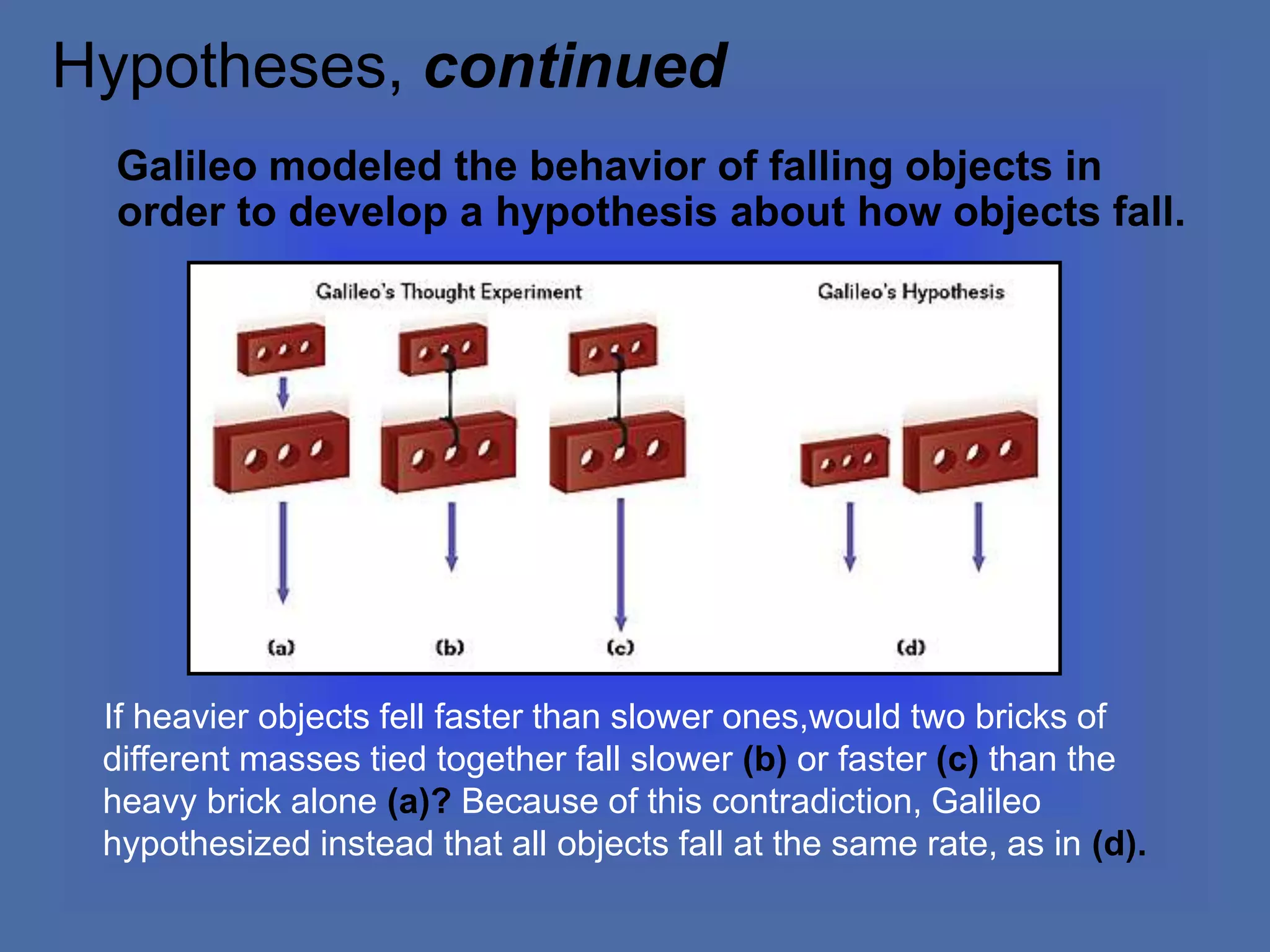

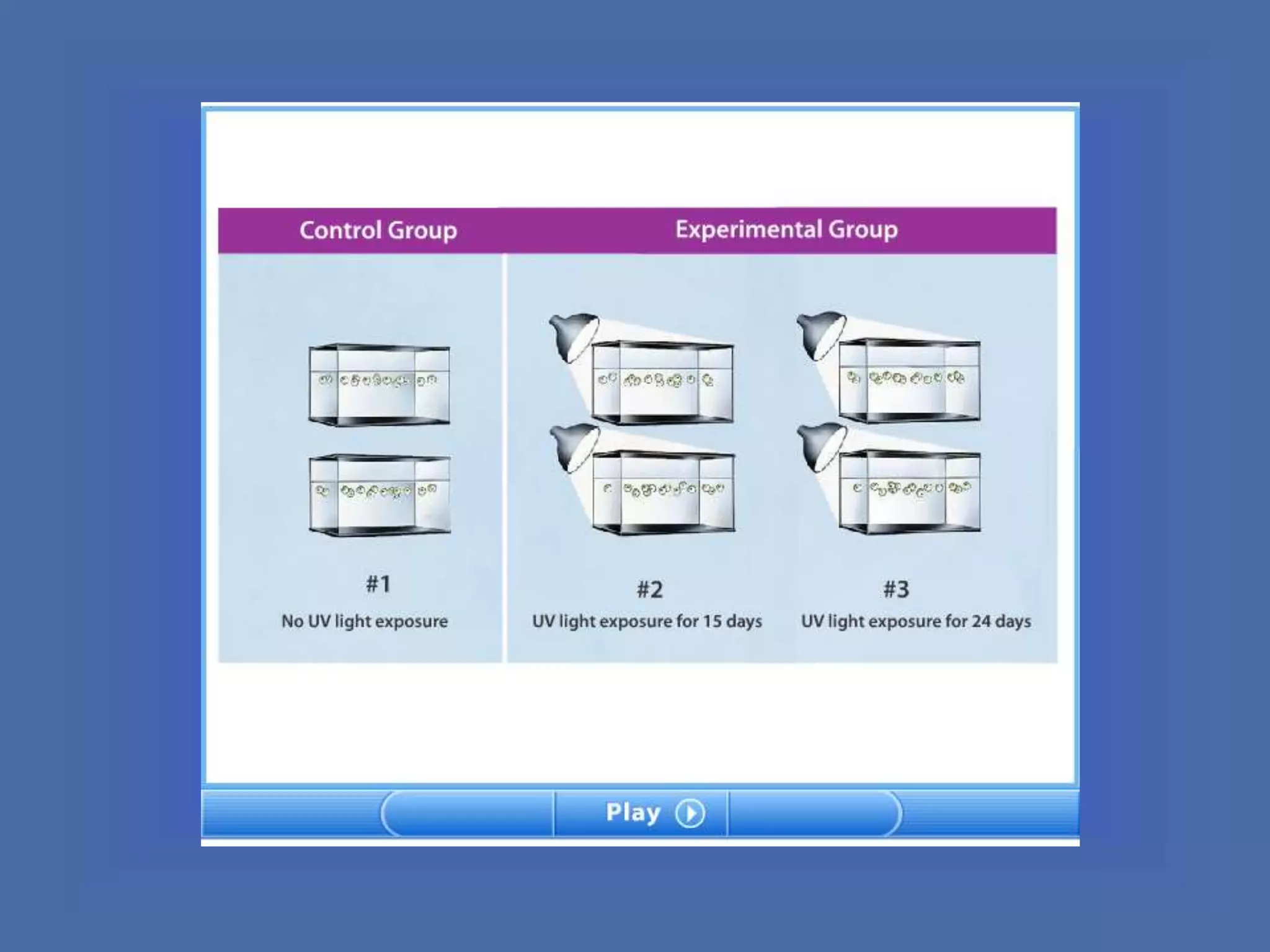

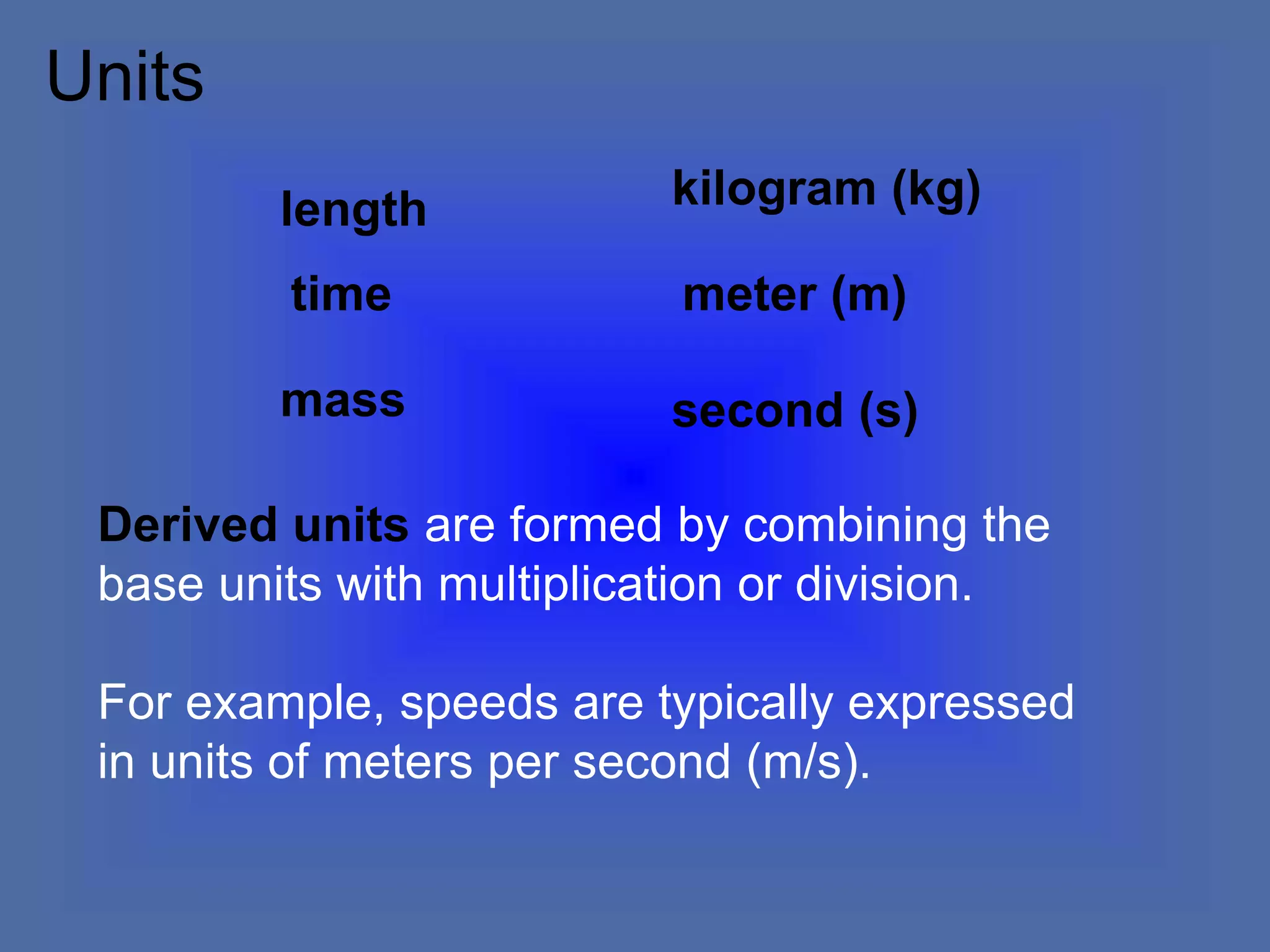

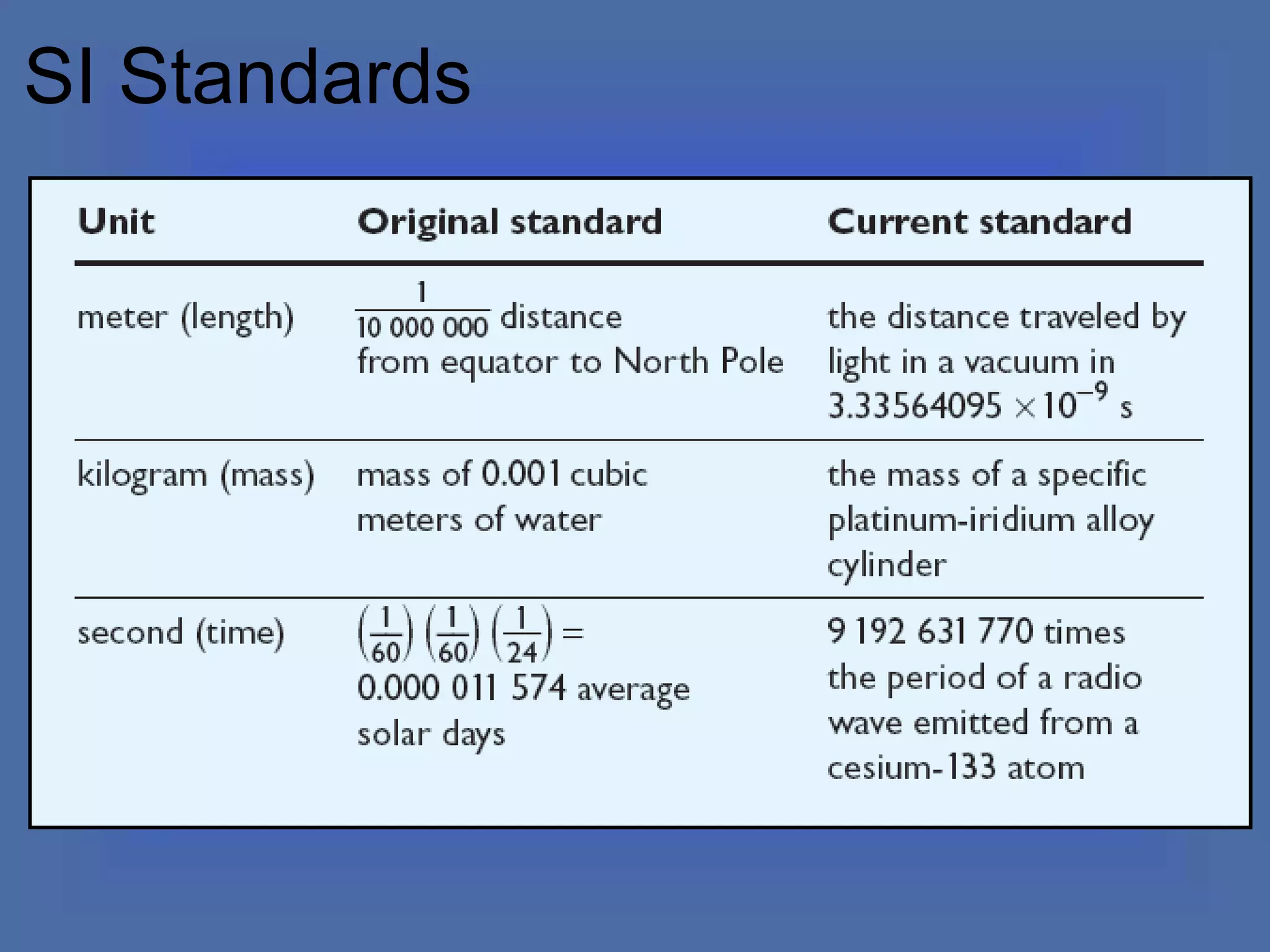

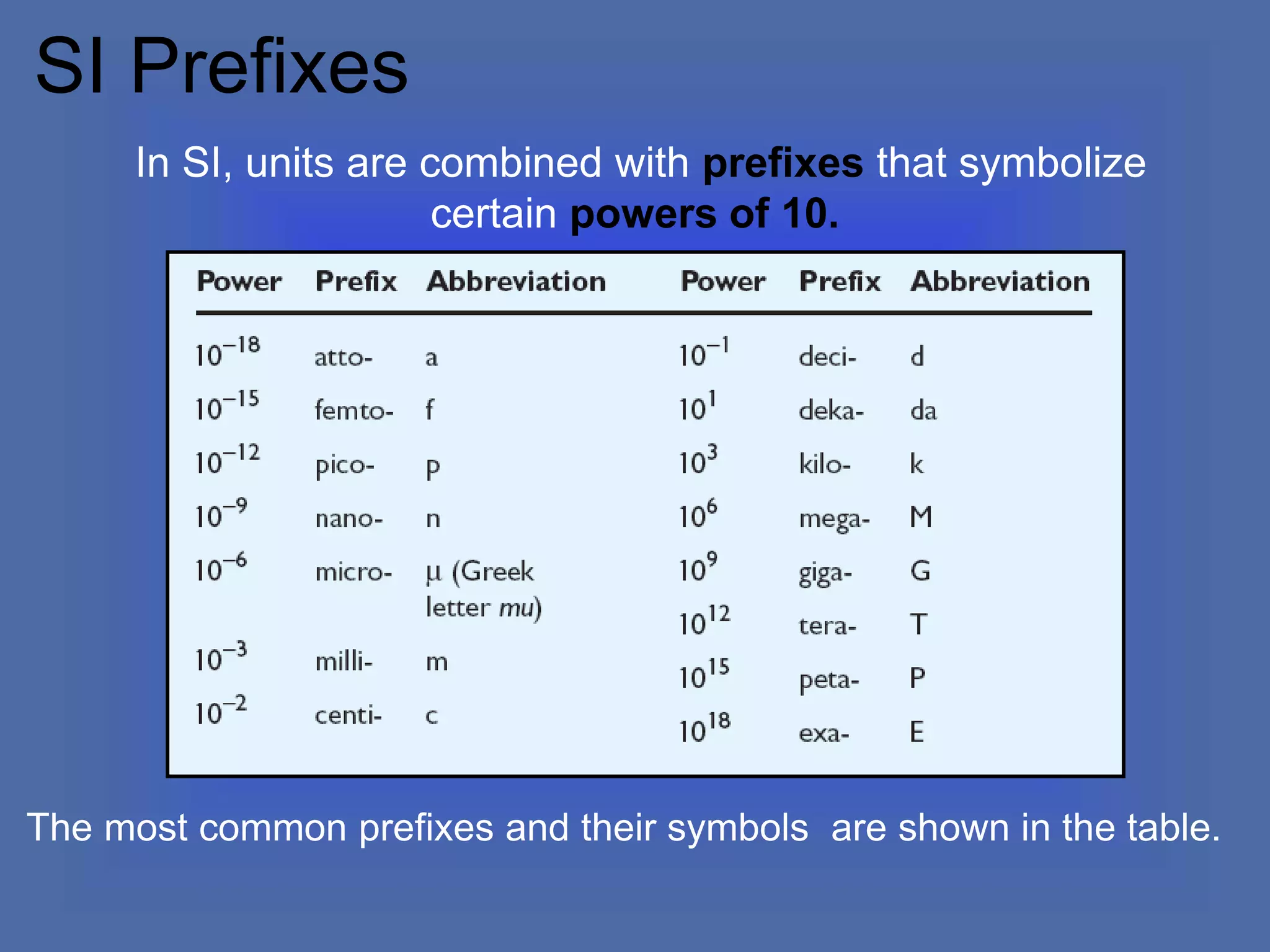

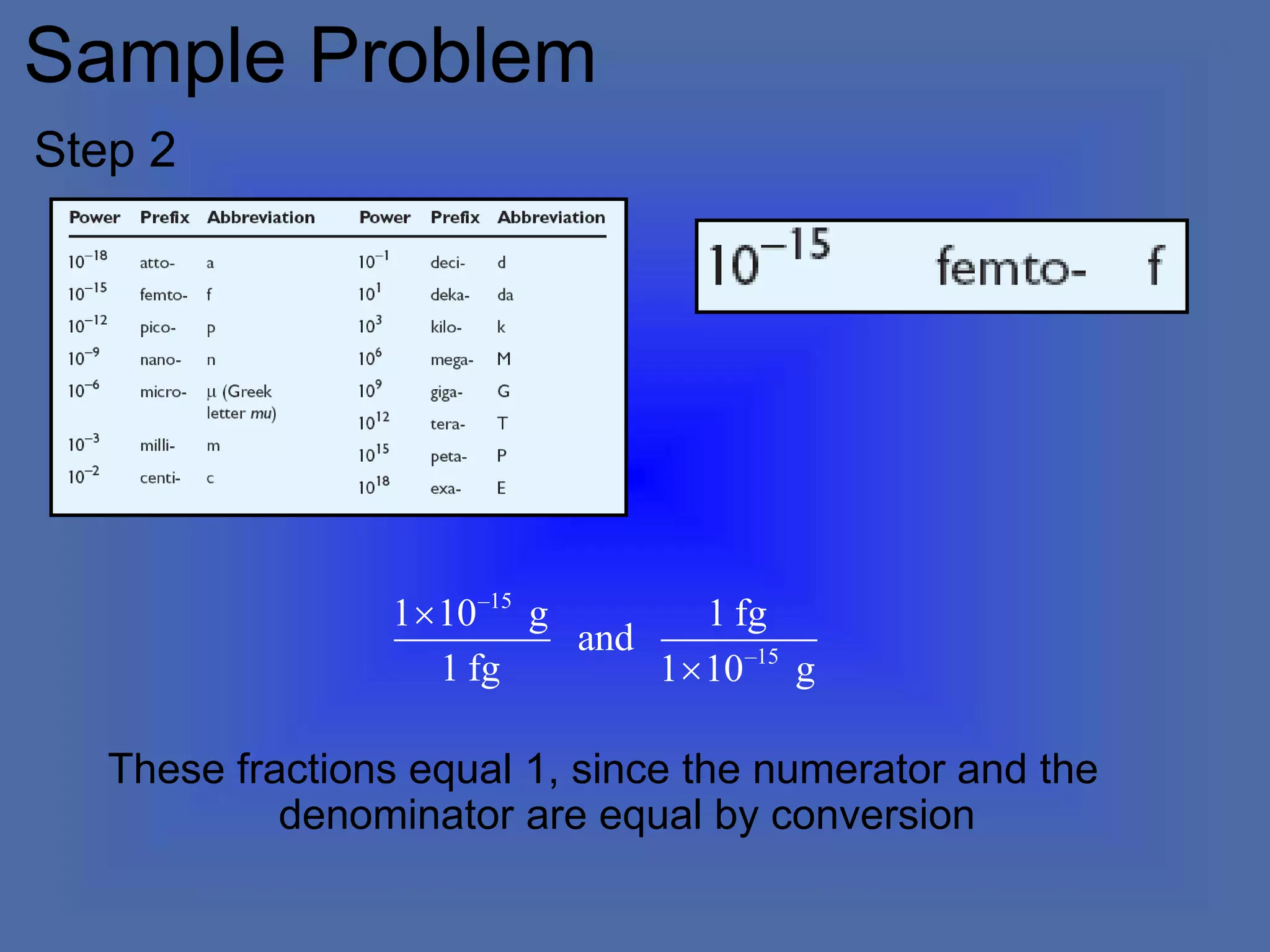

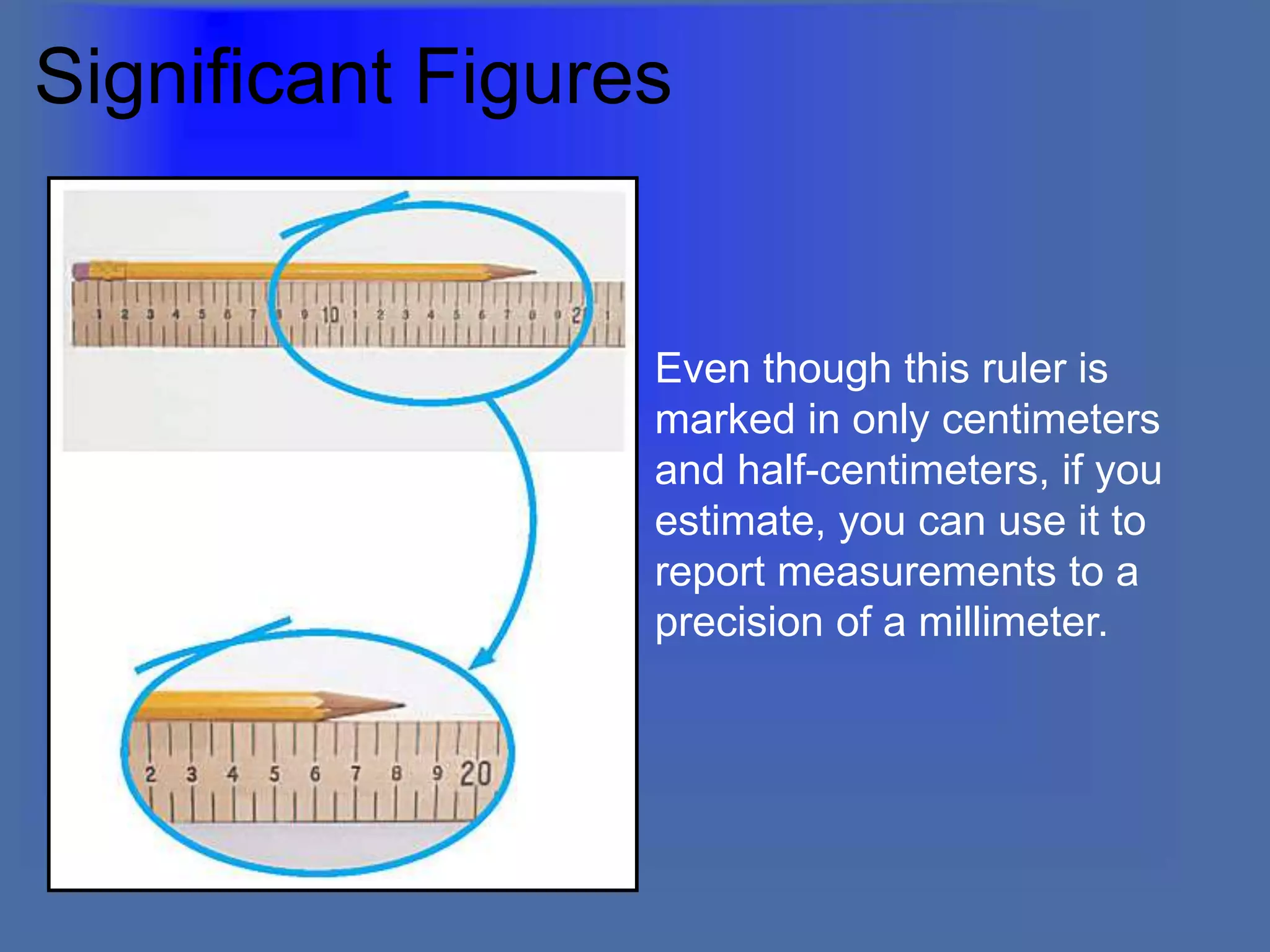

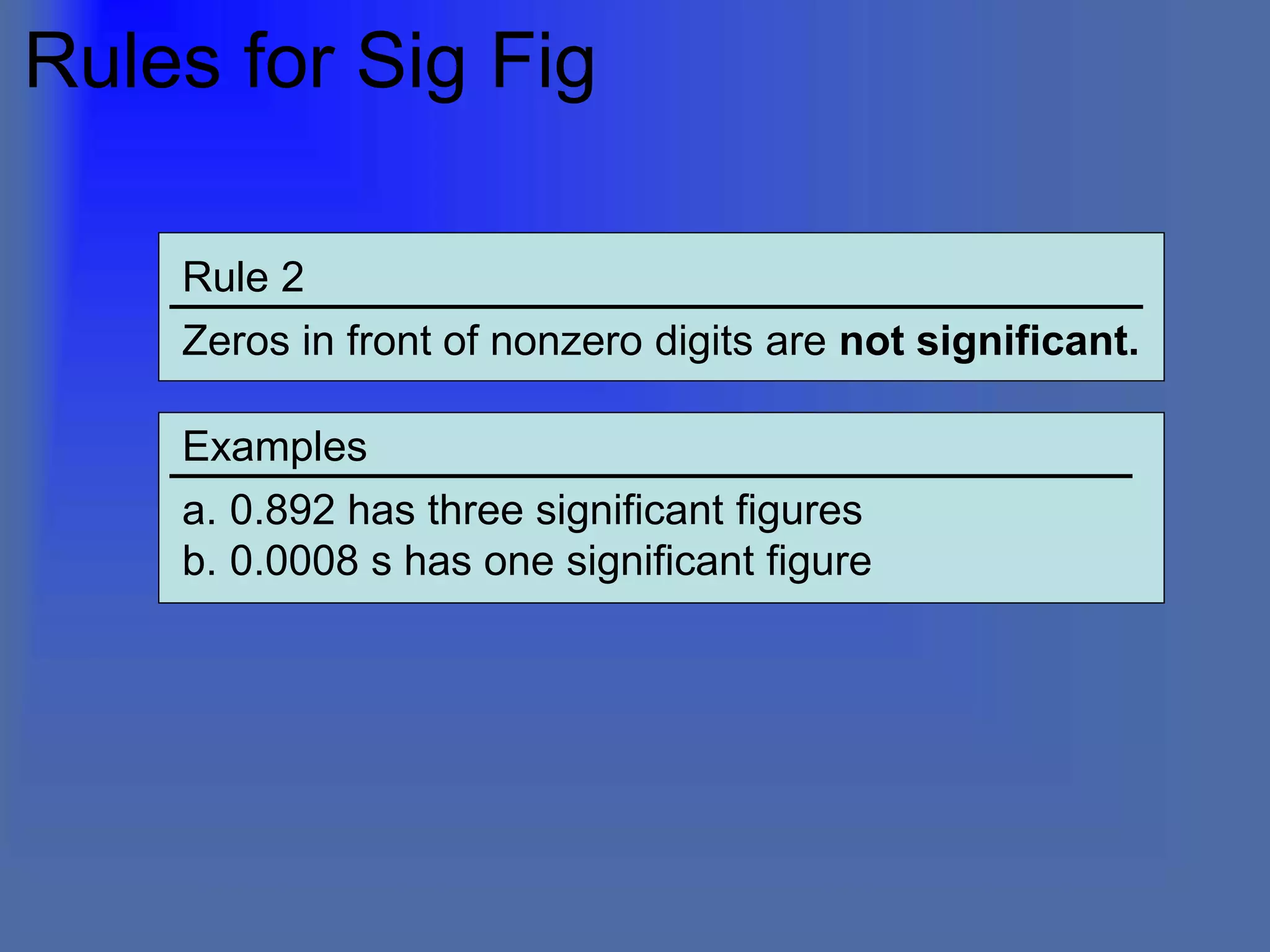

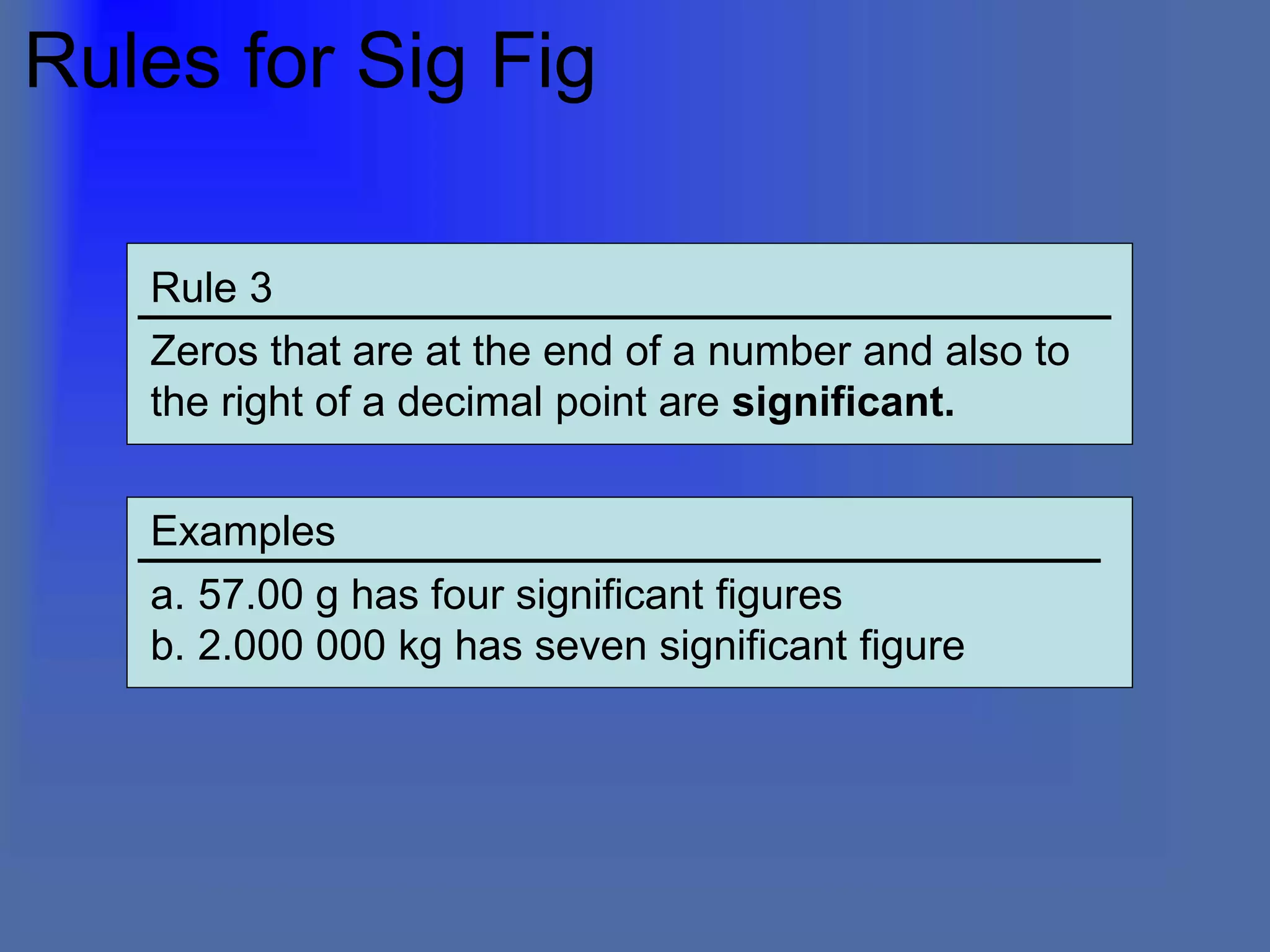

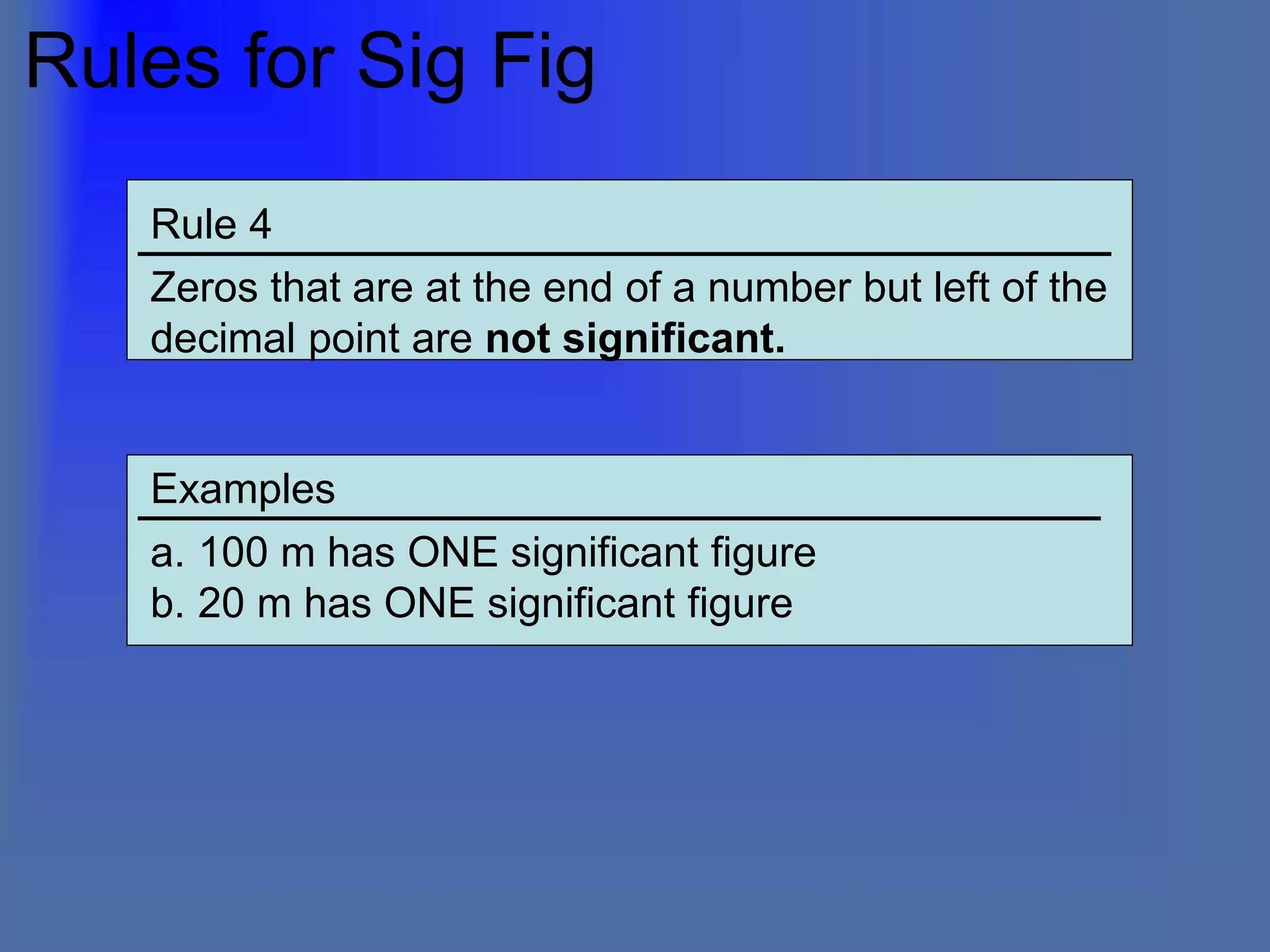

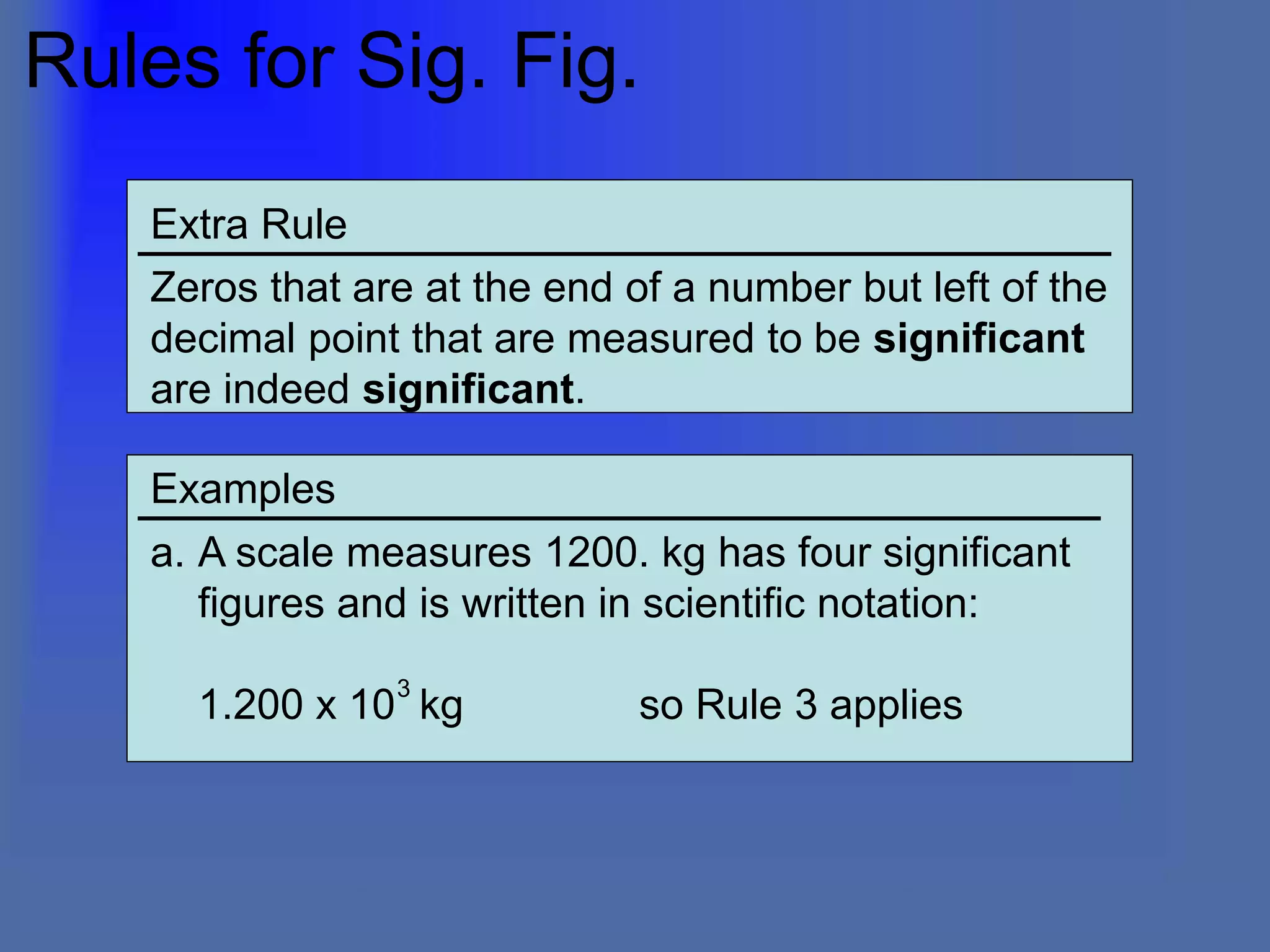

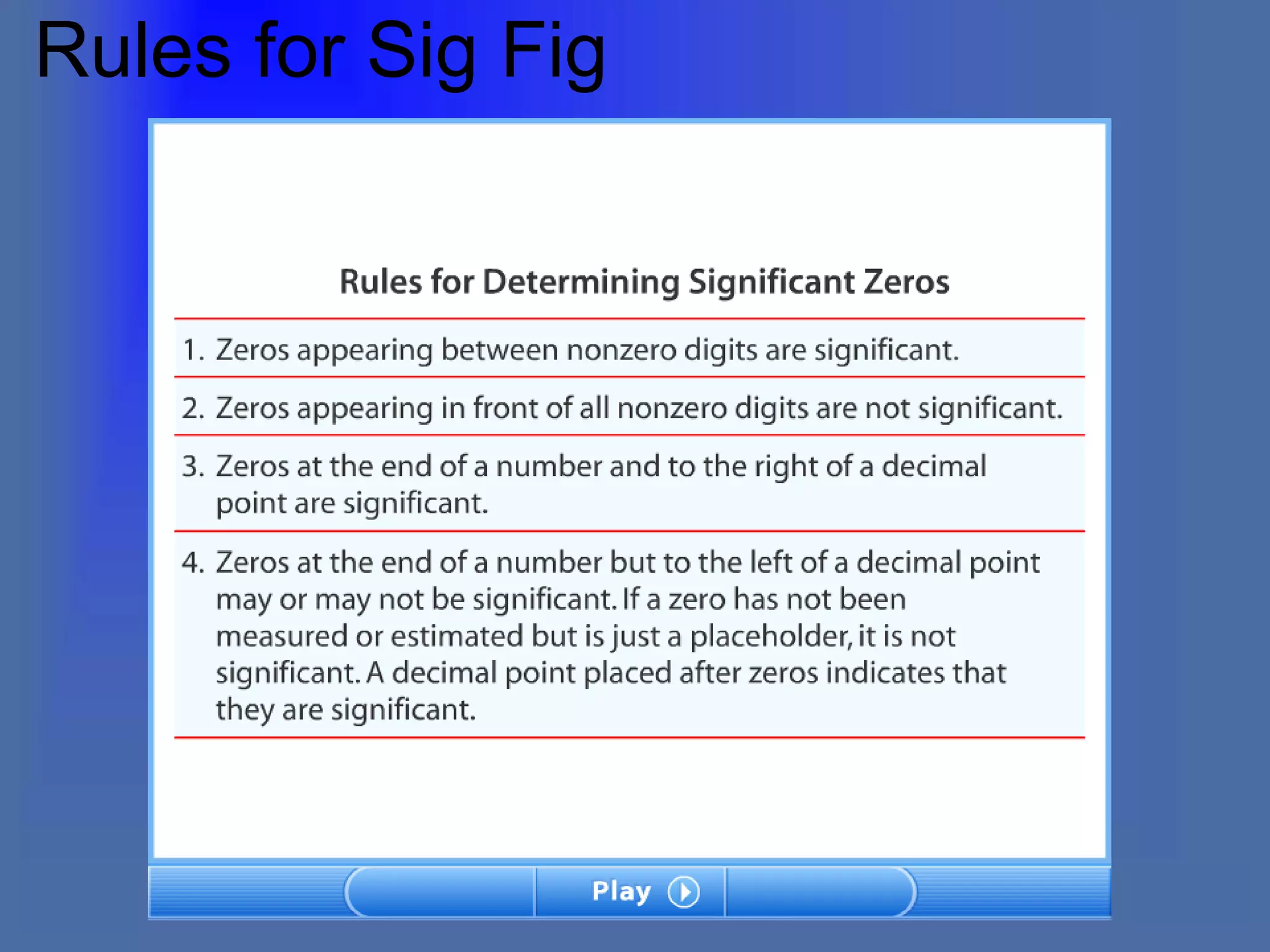

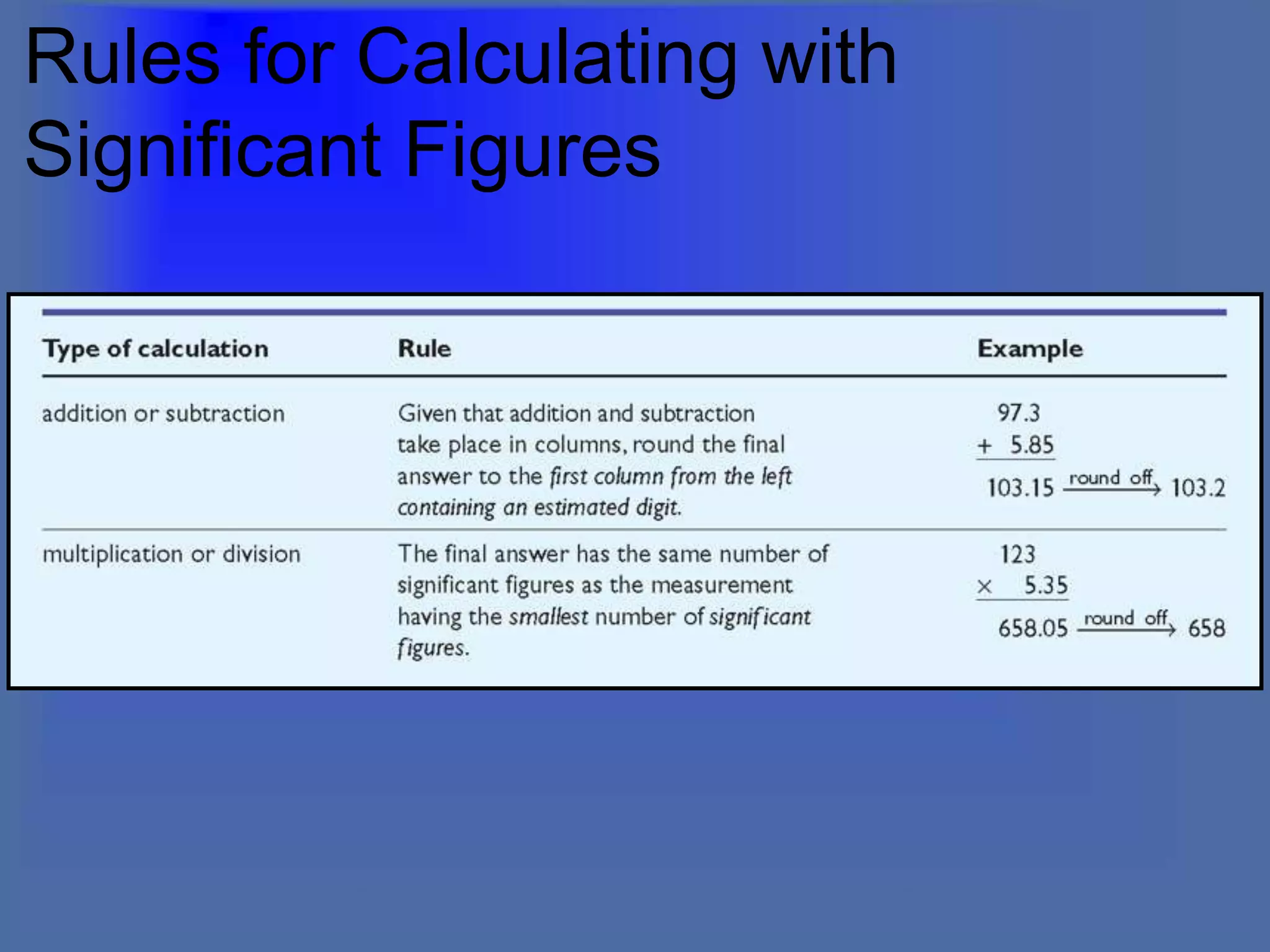

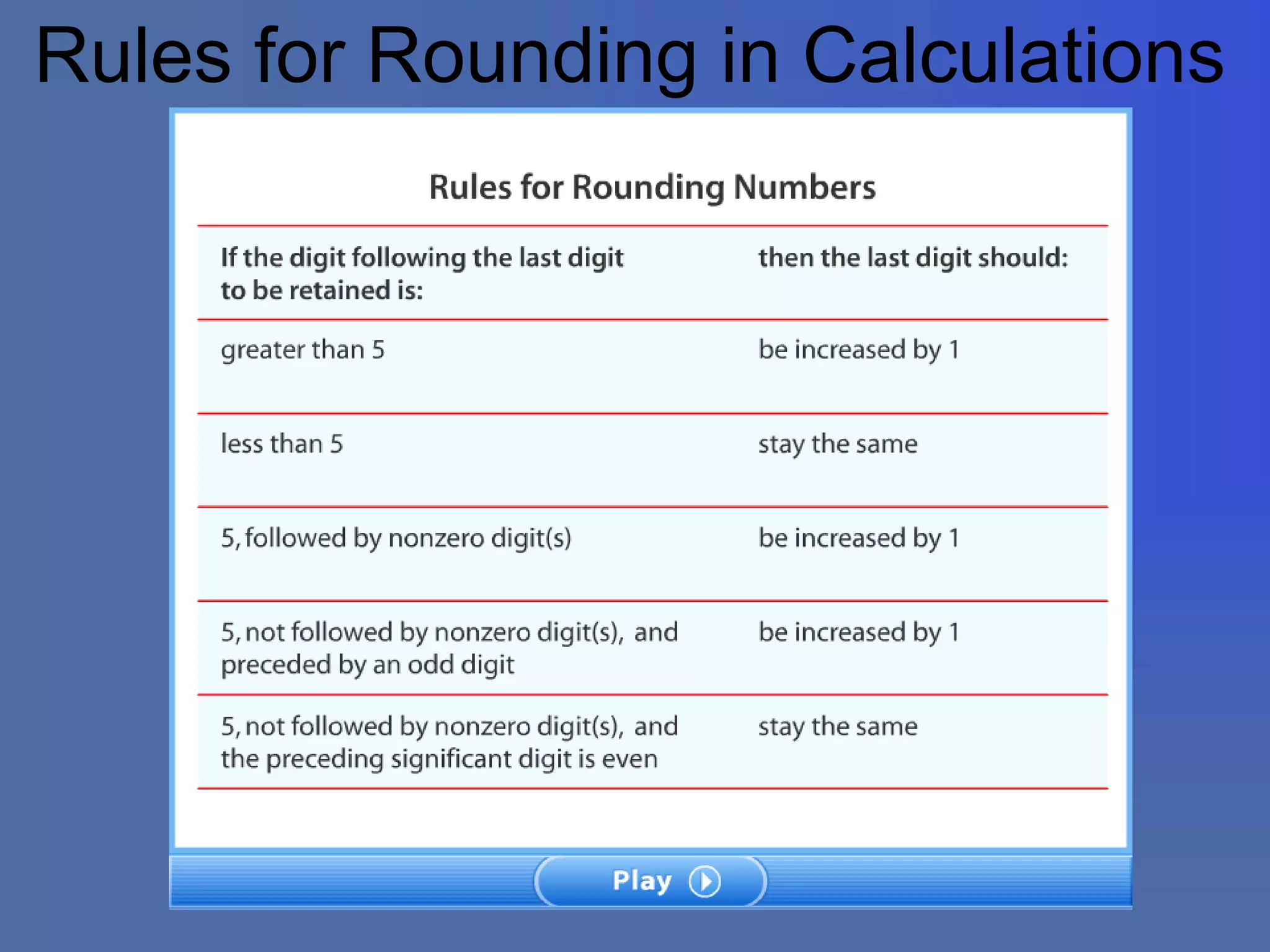

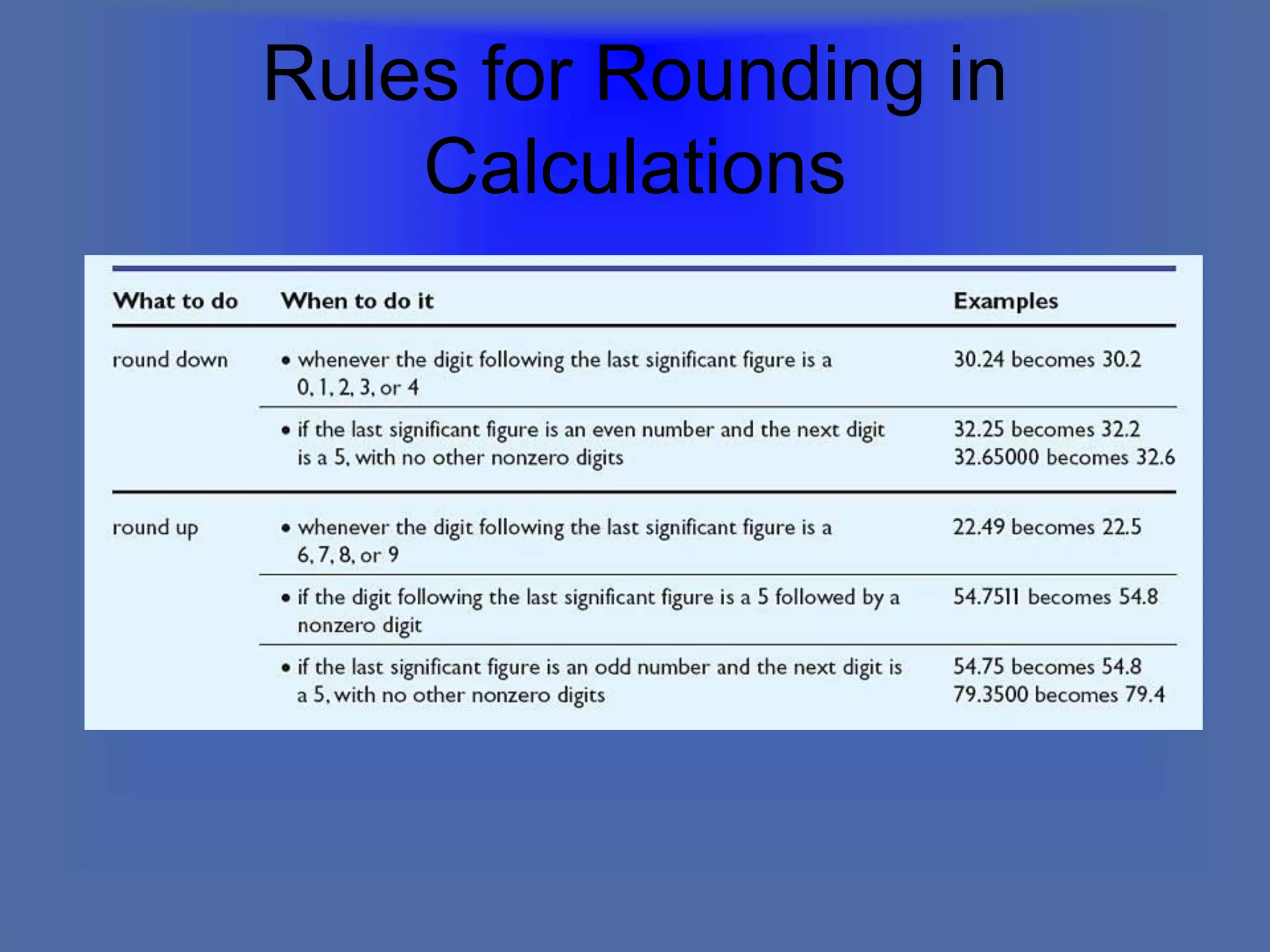

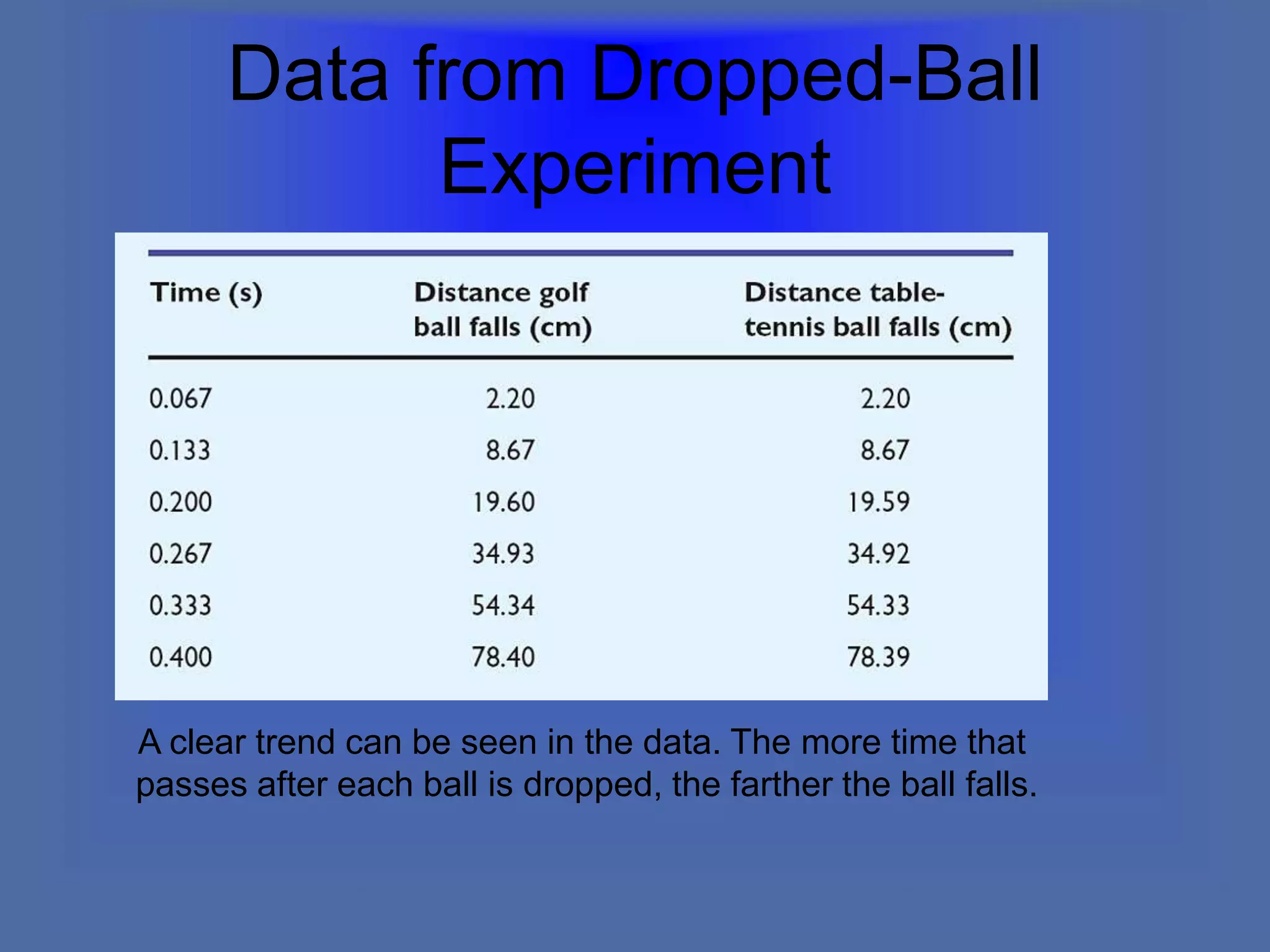

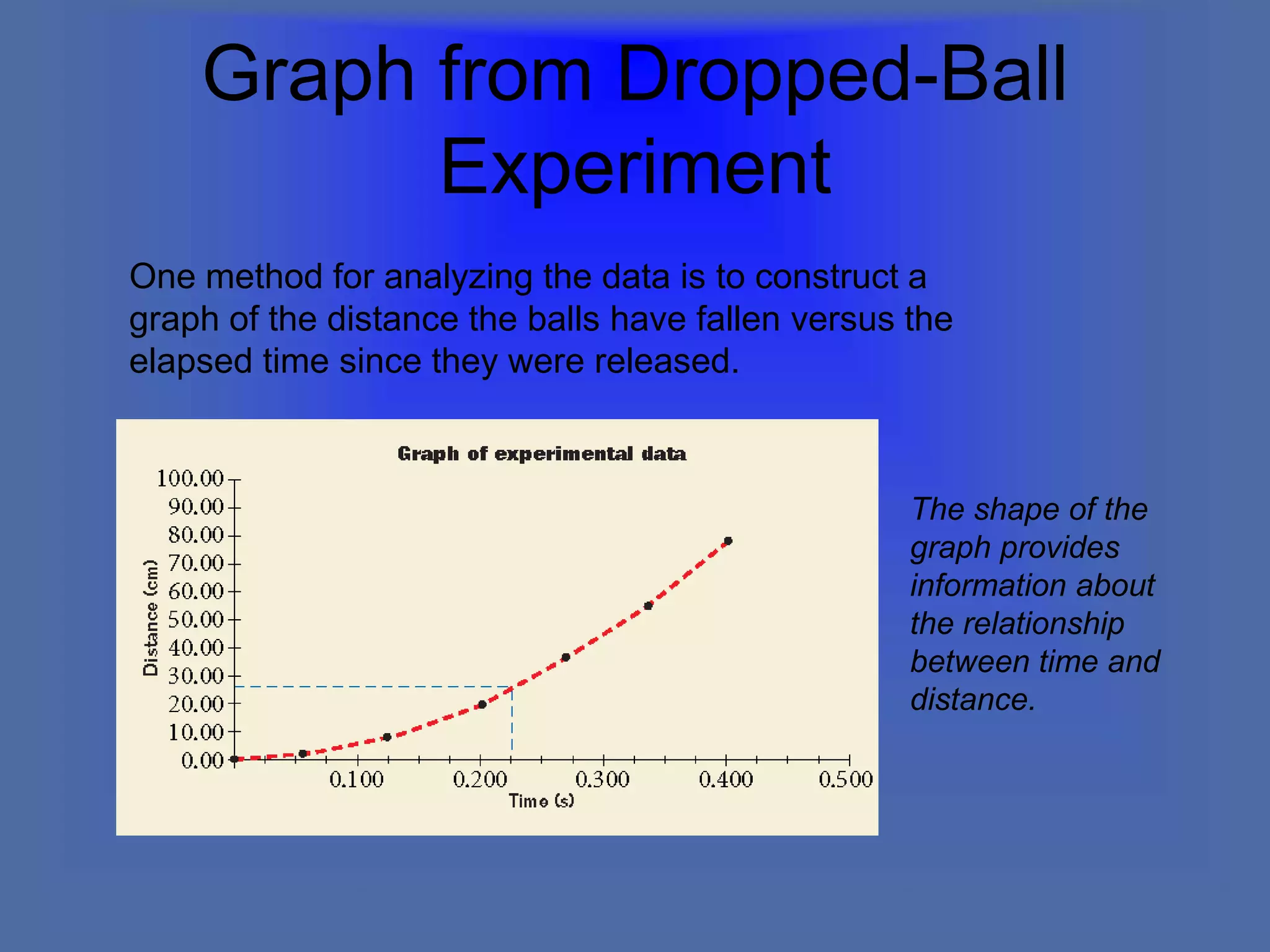

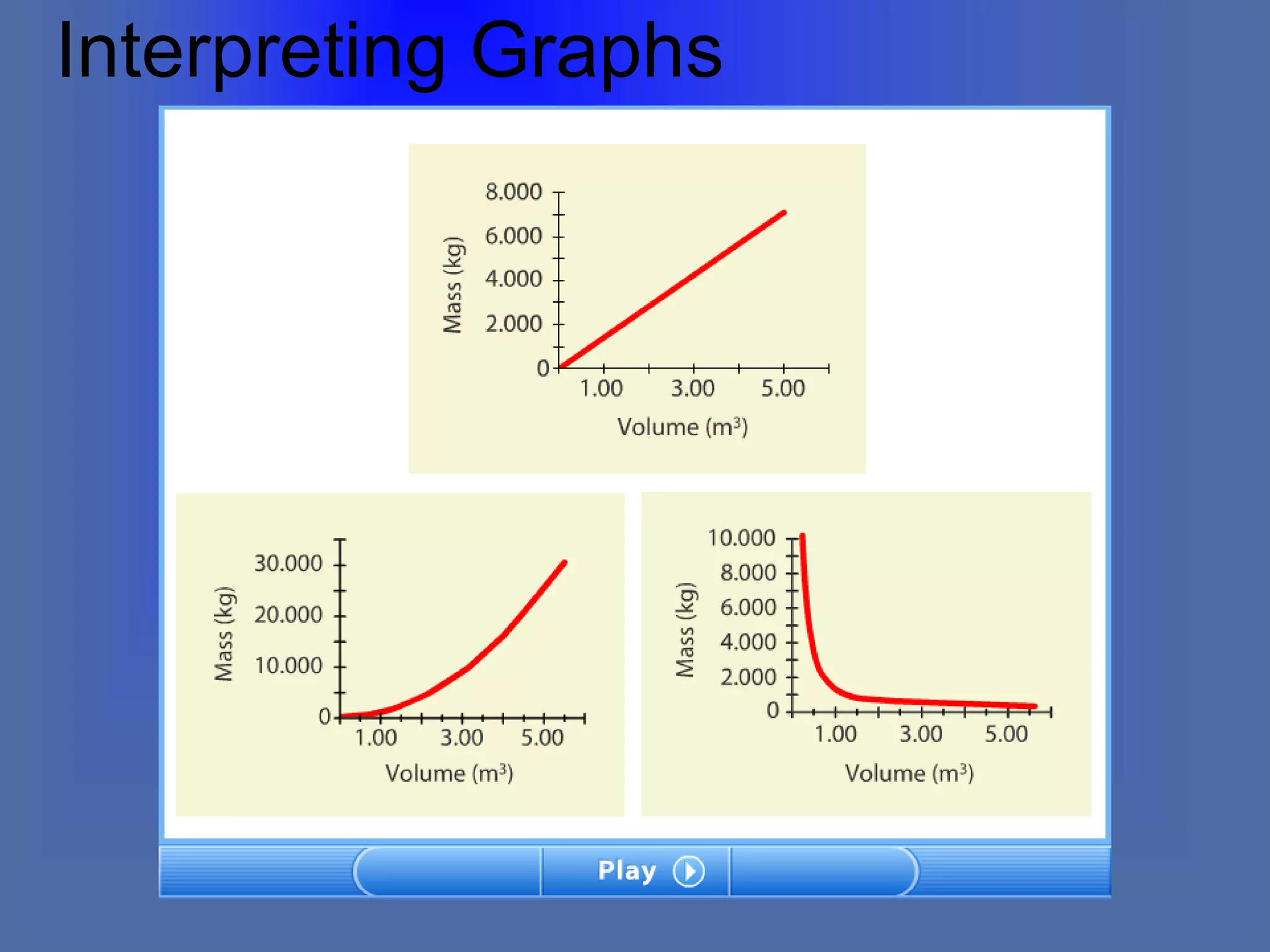

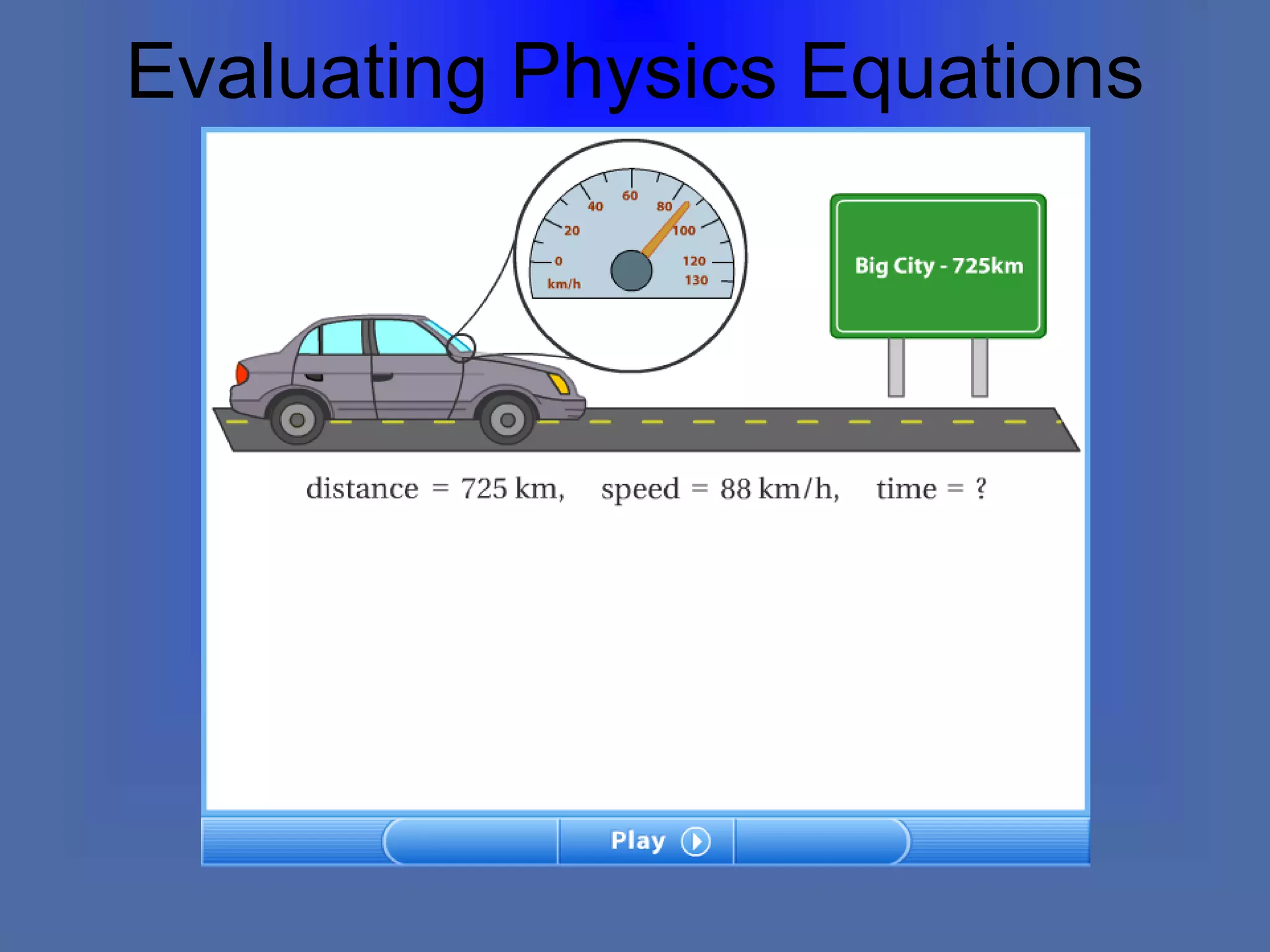

The document describes the objectives and key concepts of the first chapter of a physics textbook. It introduces the scientific method and its steps, including making observations, developing hypotheses, experimentation, and drawing conclusions. It also discusses the branches of physics, models and diagrams, units and measurements in physics, and interpreting data through tables, graphs, and equations.