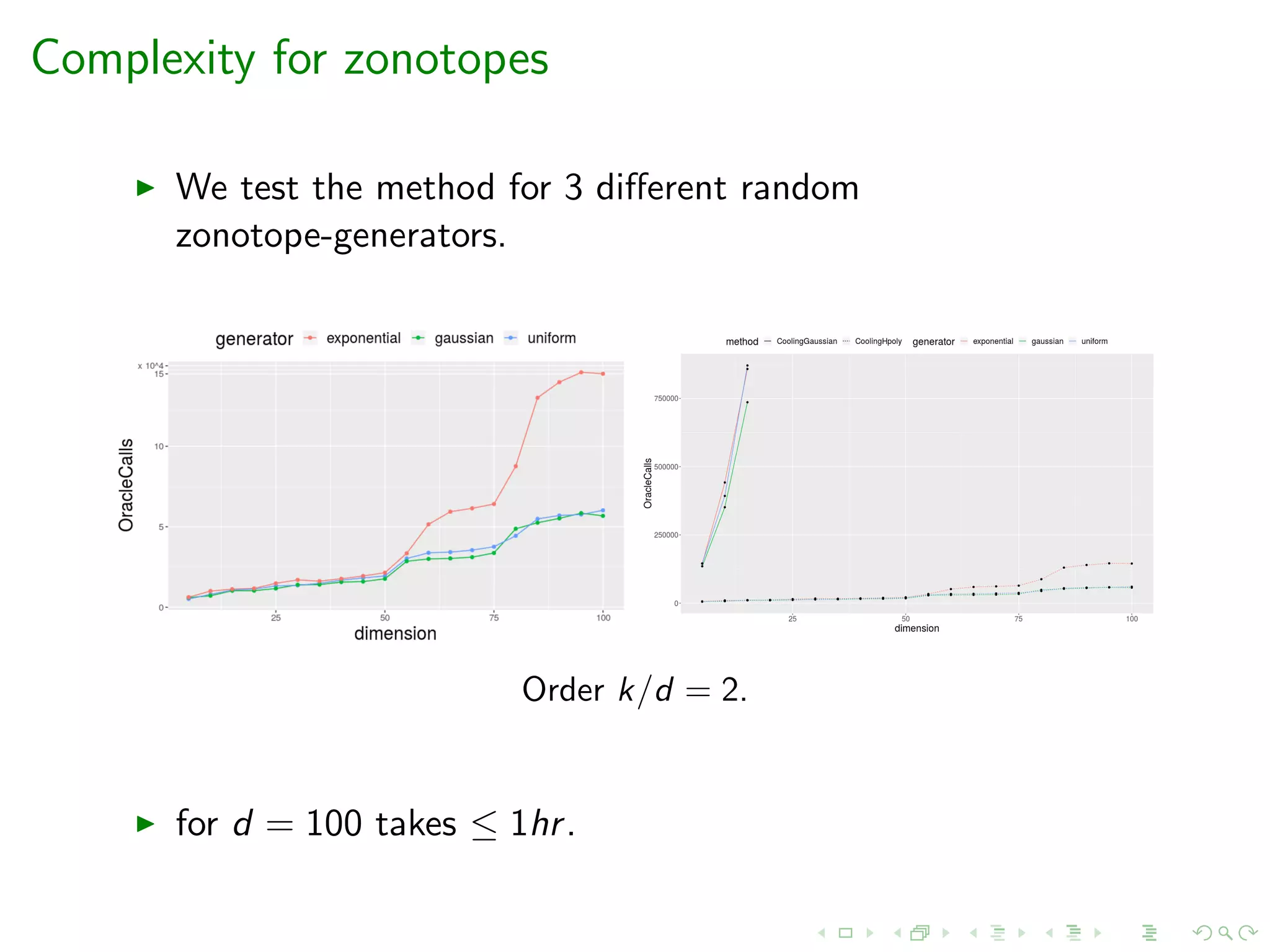

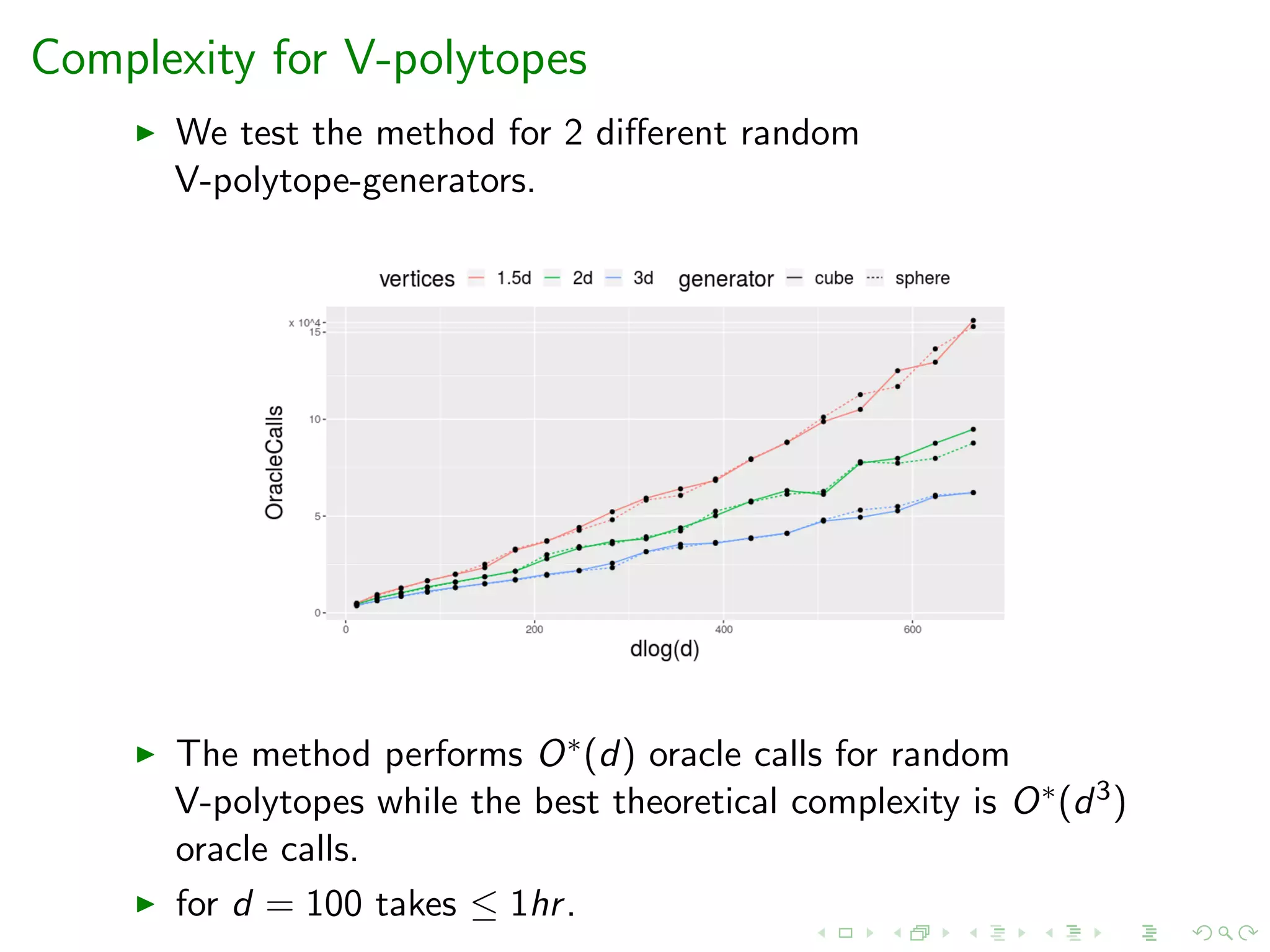

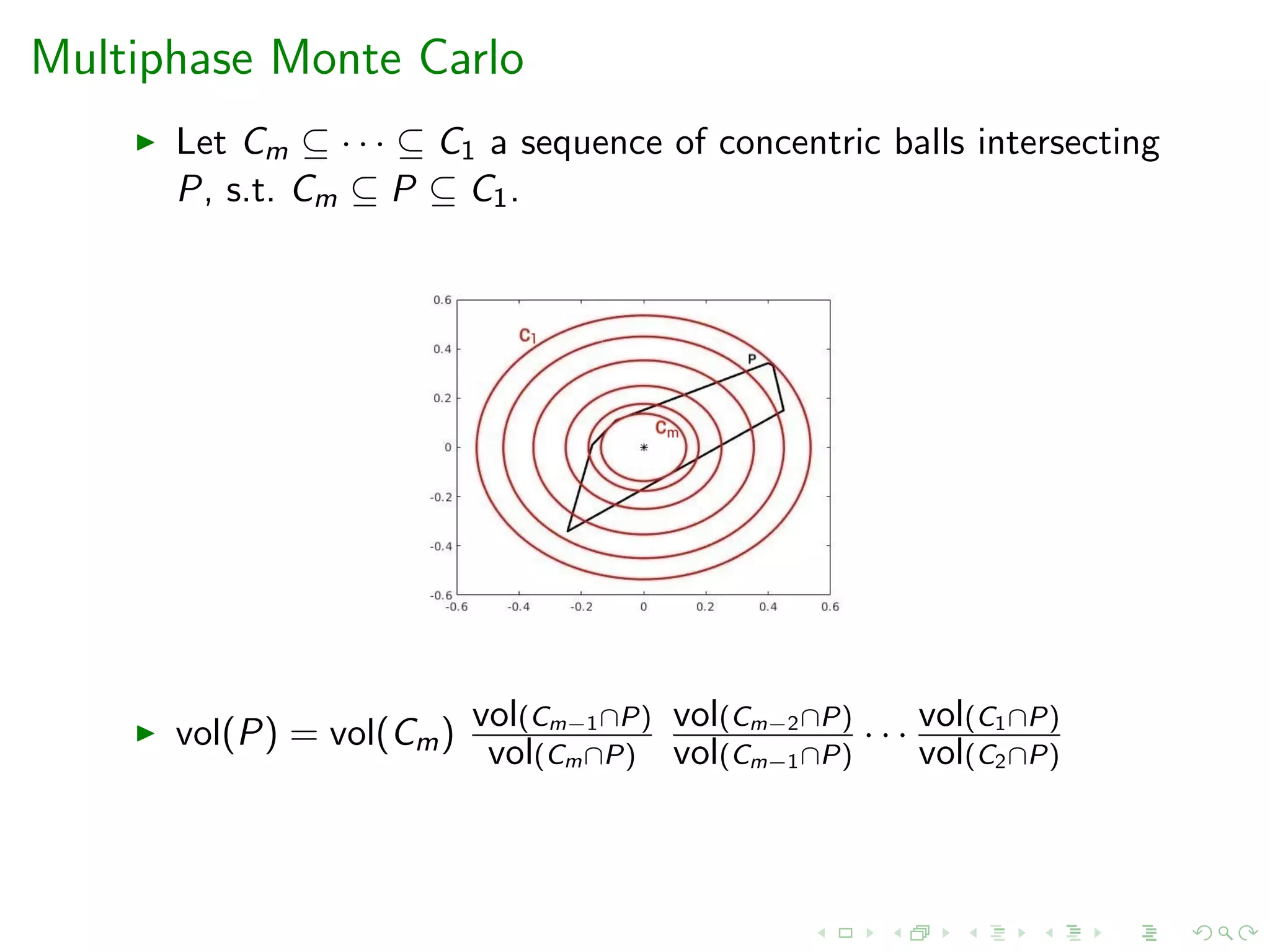

This document presents a new method for estimating the volume of convex polytopes called practical volume estimation by a new annealing schedule. It uses a multiphase Monte Carlo approach with a sequence of concentric convex bodies to approximate the volume. A new simulated annealing method constructs a sparser sequence of bodies. Billiard walk sampling is used for volume-represented and zonotope polytopes. The method scales to dimensions of 100 in an hour for random V-polytopes and zonotopes, outperforming previous methods with theoretical complexity of O*(d^3).

![Complexity

Computing the exact volume of P,

is #P-hard for all the representations [DyerFrieze’88]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/acac19-200326204311/75/14th-Athens-Colloquium-on-Algorithms-and-Complexity-ACAC19-8-2048.jpg)

![Complexity

Computing the exact volume of P,

is #P-hard for all the representations [DyerFrieze’88]

is open if both H- and V- representations available](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/acac19-200326204311/75/14th-Athens-Colloquium-on-Algorithms-and-Complexity-ACAC19-9-2048.jpg)

![Complexity

Computing the exact volume of P,

is #P-hard for all the representations [DyerFrieze’88]

is open if both H- and V- representations available

is APX-hard (oracle model) [Elekes’86]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/acac19-200326204311/75/14th-Athens-Colloquium-on-Algorithms-and-Complexity-ACAC19-10-2048.jpg)

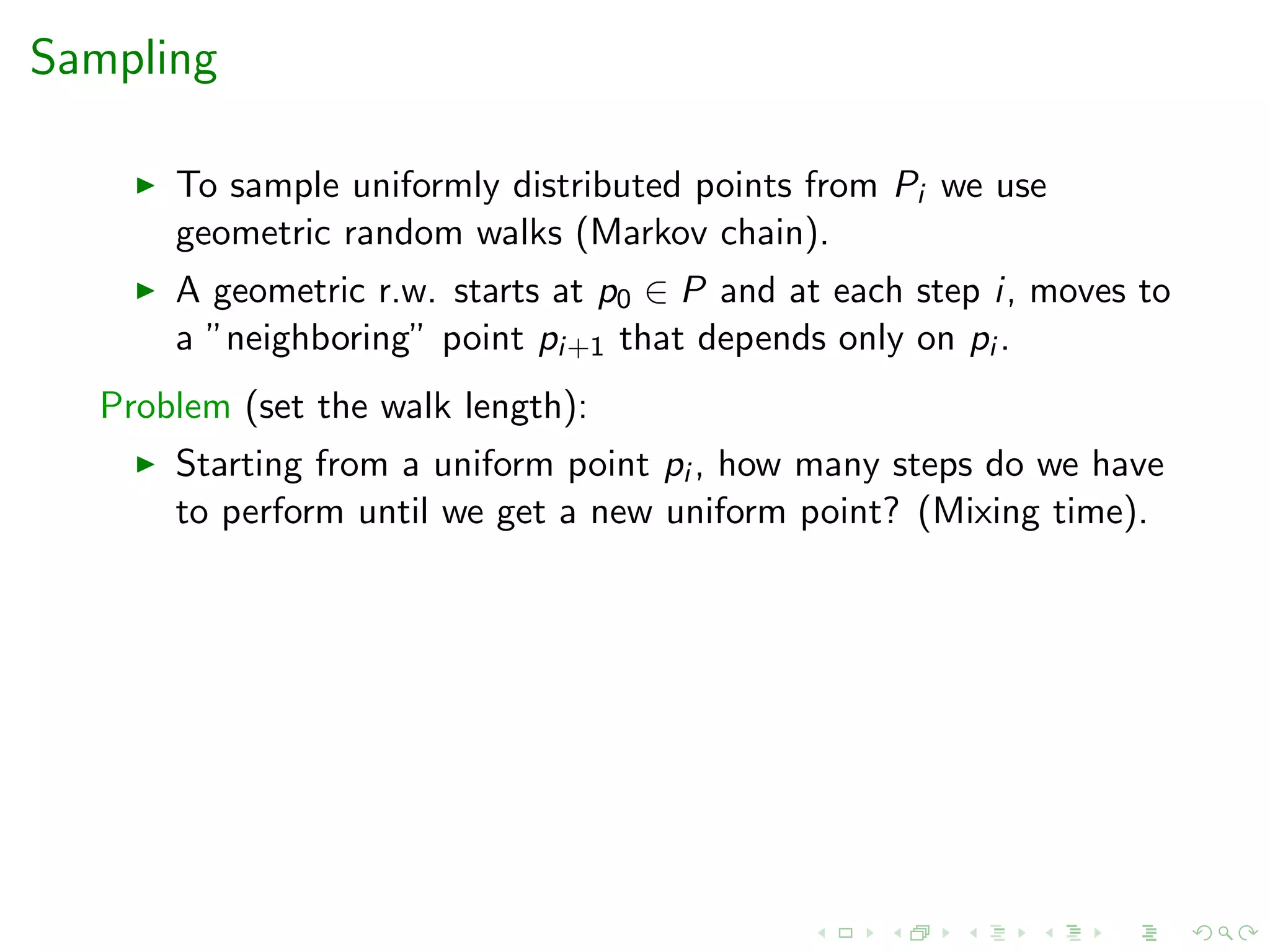

![Sampling

Random walk Mixing time cost per step cost per step

(number of steps) H-rep V- & Z-rep

Coordinate Hit-and-Run ?? O(m) 2 LPs

Billiard walk ?? O(ρmd) ρ LPs

Coordinate Hit-and-Run:

Is the main paradigm in applications and software.

In practice converges to uniform distribution in O(d2) steps

[Cousins, Vempala’17].](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/acac19-200326204311/75/14th-Athens-Colloquium-on-Algorithms-and-Complexity-ACAC19-25-2048.jpg)

![Sampling

Random walk Mixing time cost per step cost per step

(number of steps) H-rep V- & Z-rep

Coordinate Hit-and-Run ?? O(m) 2 LPs

Billiard walk ?? O(ρmd) ρ LPs

Coordinate Hit-and-Run:

Is the main paradigm in applications and software.

In practice converges to uniform distribution in O(d2) steps

[Cousins, Vempala’17].

Billiard walk:

Converges faster to uniform distribution than Hit-and-Run in

practice [Polyak’14].

For V-polytopes and zonotopes has comparable cost per step

with Coordinate Hit-and-Run.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/acac19-200326204311/75/14th-Athens-Colloquium-on-Algorithms-and-Complexity-ACAC19-26-2048.jpg)

![State-of-the-art

Authors-Year Complexity Algorithm

(oracle calls)

[Dyer, Frieze, Kannan’91] O∗(d23) Sequence of balls + grid walk

[Kannan, Lovasz, Simonovits’97] O∗(d5) Sequence of balls + ball walk

[Lovasz, Vempala’03] O∗(d4) Exponential dist. + hit-and-run

[Cousins, Vempala’15] O∗(d3) Spherical Gaussians + ball walk](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/acac19-200326204311/75/14th-Athens-Colloquium-on-Algorithms-and-Complexity-ACAC19-28-2048.jpg)

![State-of-the-art

Authors-Year Complexity Algorithm

(oracle calls)

[Dyer, Frieze, Kannan’91] O∗(d23) Sequence of balls + grid walk

[Kannan, Lovasz, Simonovits’97] O∗(d5) Sequence of balls + ball walk

[Lovasz, Vempala’03] O∗(d4) Exponential dist. + hit-and-run

[Cousins, Vempala’15] O∗(d3) Spherical Gaussians + ball walk

Practical methods:

Follow theory but make practical adjustments (experimental).](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/acac19-200326204311/75/14th-Athens-Colloquium-on-Algorithms-and-Complexity-ACAC19-29-2048.jpg)

![State-of-the-art

Authors-Year Complexity Algorithm

(oracle calls)

[Dyer, Frieze, Kannan’91] O∗(d23) Sequence of balls + grid walk

[Kannan, Lovasz, Simonovits’97] O∗(d5) Sequence of balls + ball walk

[Lovasz, Vempala’03] O∗(d4) Exponential dist. + hit-and-run

[Cousins, Vempala’15] O∗(d3) Spherical Gaussians + ball walk

Practical methods:

Follow theory but make practical adjustments (experimental).

[Emiris, F’14] Sequence of balls + coordinate hit-and-run.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/acac19-200326204311/75/14th-Athens-Colloquium-on-Algorithms-and-Complexity-ACAC19-30-2048.jpg)

![State-of-the-art

Authors-Year Complexity Algorithm

(oracle calls)

[Dyer, Frieze, Kannan’91] O∗(d23) Sequence of balls + grid walk

[Kannan, Lovasz, Simonovits’97] O∗(d5) Sequence of balls + ball walk

[Lovasz, Vempala’03] O∗(d4) Exponential dist. + hit-and-run

[Cousins, Vempala’15] O∗(d3) Spherical Gaussians + ball walk

Practical methods:

Follow theory but make practical adjustments (experimental).

[Emiris, F’14] Sequence of balls + coordinate hit-and-run.

[Cousins, Vempala’16] Spherical Gaussians + coordinate

hit-and-run](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/acac19-200326204311/75/14th-Athens-Colloquium-on-Algorithms-and-Complexity-ACAC19-31-2048.jpg)

![Limitations

Limitations of existing practical methods:

Efficient only for H-polytopes (scale up-to few hundred dims in

hrs)

For V-polytopes or zonotopes:

Both of them request an inscribed ball (ideally the maximum)

C ⊆ P.

The number of total steps is strongly determined by the radius

of C.

[Cousins, Vempala’16] needs a bound on the number of facets.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/acac19-200326204311/75/14th-Athens-Colloquium-on-Algorithms-and-Complexity-ACAC19-33-2048.jpg)

![Our contributions

Multiphase Monte Carlo: We allow any convex body C (that

”fits well” to P and is ”easy” to sample from) besides ball to

construct the sequence.

Sampling: Billiard walk to V-polytopes and zonotopes.

A new simulated annealing method to construct a sparser

sequence of bodies.

Sequence by [L.S.’97] (left) and by annealing schedule (right).](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/acac19-200326204311/75/14th-Athens-Colloquium-on-Algorithms-and-Complexity-ACAC19-36-2048.jpg)

![Our contributions

Multiphase Monte Carlo: We allow any convex body C (that

”fits well” to P and is ”easy” to sample from) besides ball to

construct the sequence.

Sampling: Billiard walk to V-polytopes and zonotopes.

A new simulated annealing method to construct a sparser

sequence of bodies.

Sequence by [L.S.’97] (left) and by annealing schedule (right).

Our method can be easily extended for any polytope P that is

given as a projection of a polytope Q.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/acac19-200326204311/75/14th-Athens-Colloquium-on-Algorithms-and-Complexity-ACAC19-37-2048.jpg)

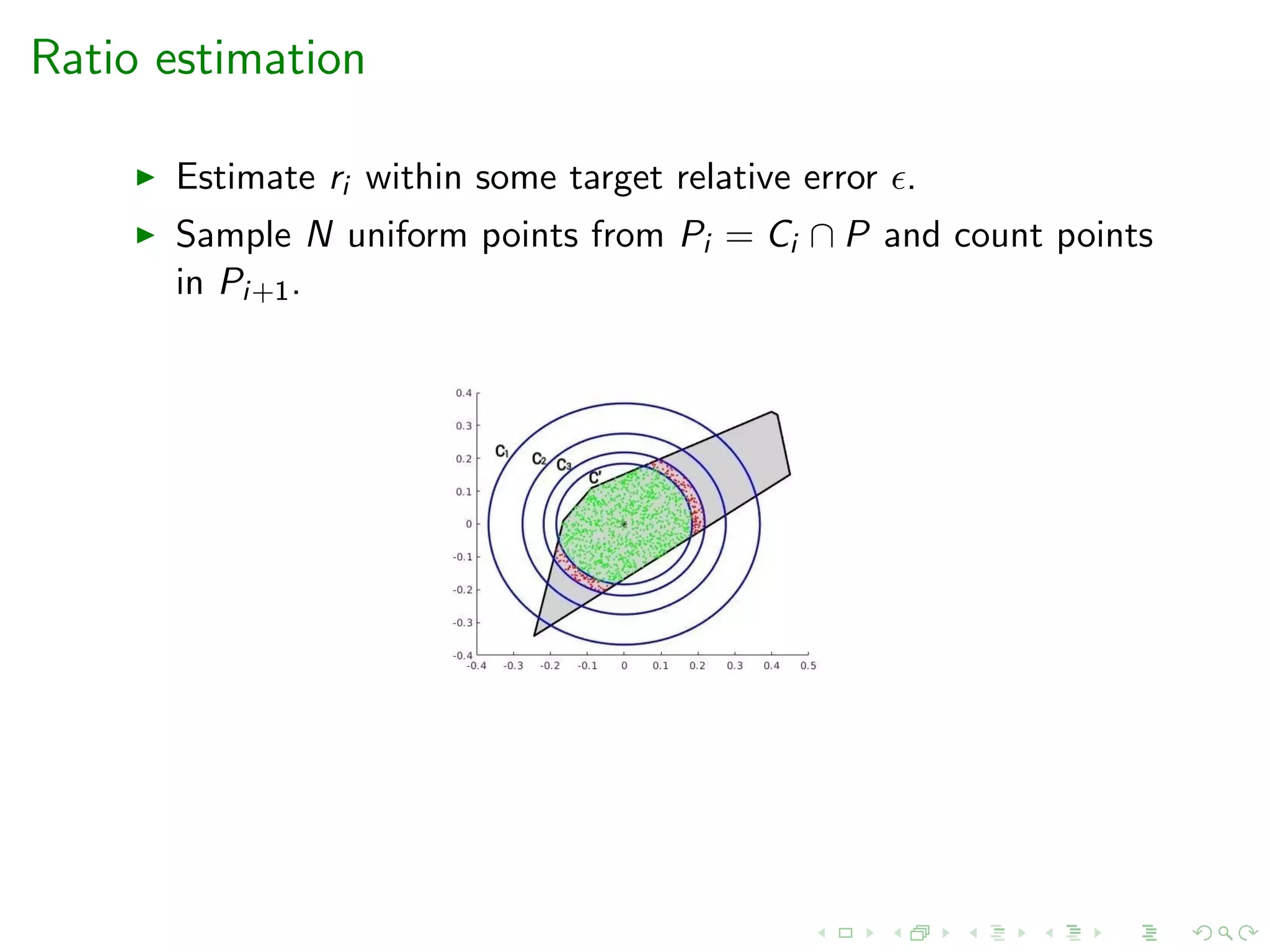

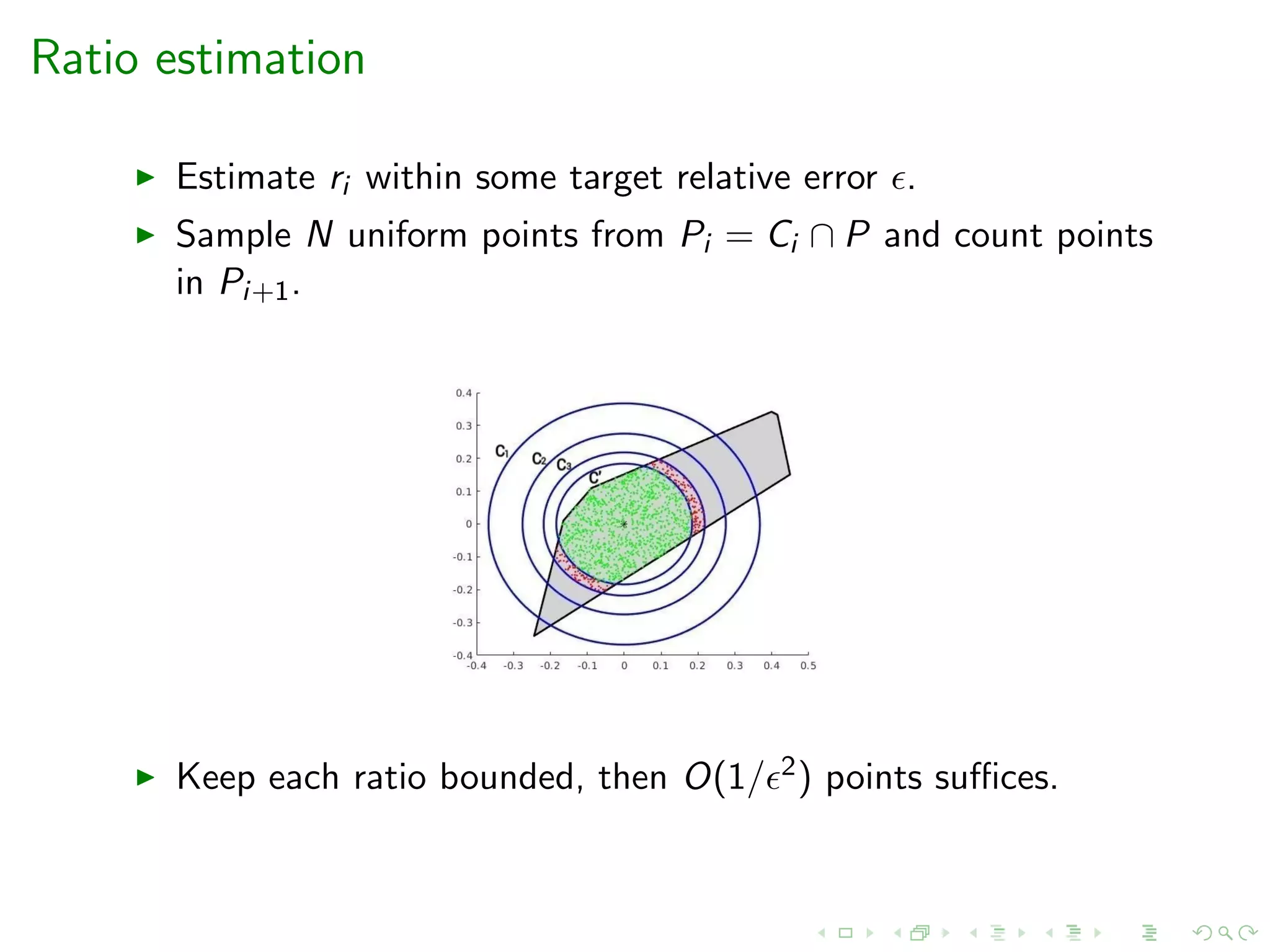

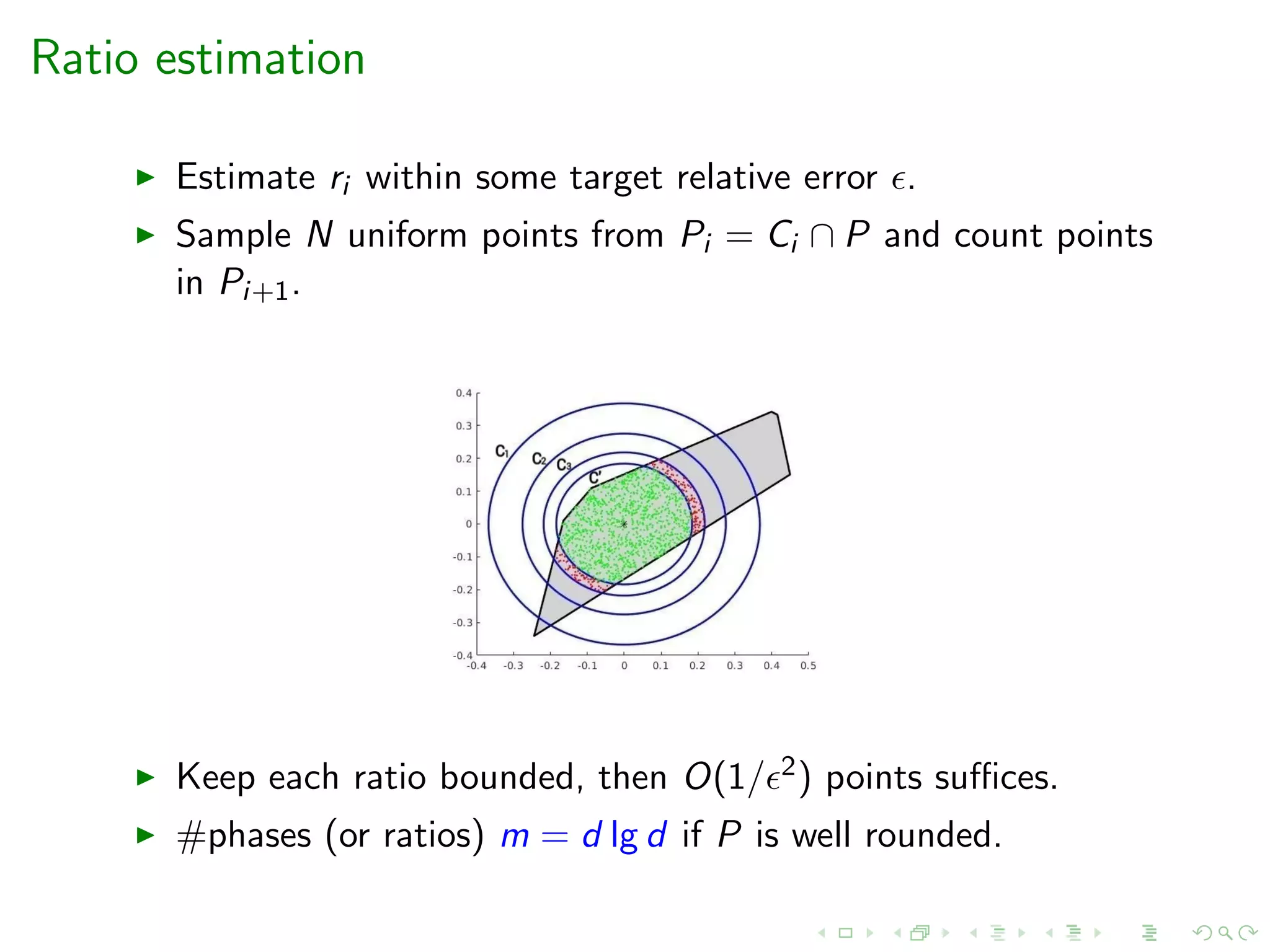

![Annealing Schedule

Inputs: Polytope P, body C, cooling parameters r, δ > 0.

Output: A sequence of scaled copies of C, Cm ⊆ · · · ⊆ C1 s.t.

vol(Pi+1)/vol(Pi ) ∈ [r, r + δ] with high probability

where Pi = Ci ∩ P, i = 1, . . . , m and P0 = P.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/acac19-200326204311/75/14th-Athens-Colloquium-on-Algorithms-and-Complexity-ACAC19-38-2048.jpg)

![Statistical tests

for the ratio of volumes of convex bodies

Given convex bodies Pi ⊇ Pi+1, we define two statistical tests:

testL(Pi , Pi+1, r, δ): testR(Pi , Pi+1, r, δ):

H0 : vol(Pi+1)/vol(Pi ) ≥ r + δ H0 : vol(Pi+1)/vol(Pi ) ≤ r

Successful if we reject H0 Successful if we reject H0

If both testL and testR are successful then

ri = vol(Pi+1)/vol(Pi ) ∈ [r, r + δ], with high probability.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/acac19-200326204311/75/14th-Athens-Colloquium-on-Algorithms-and-Complexity-ACAC19-39-2048.jpg)

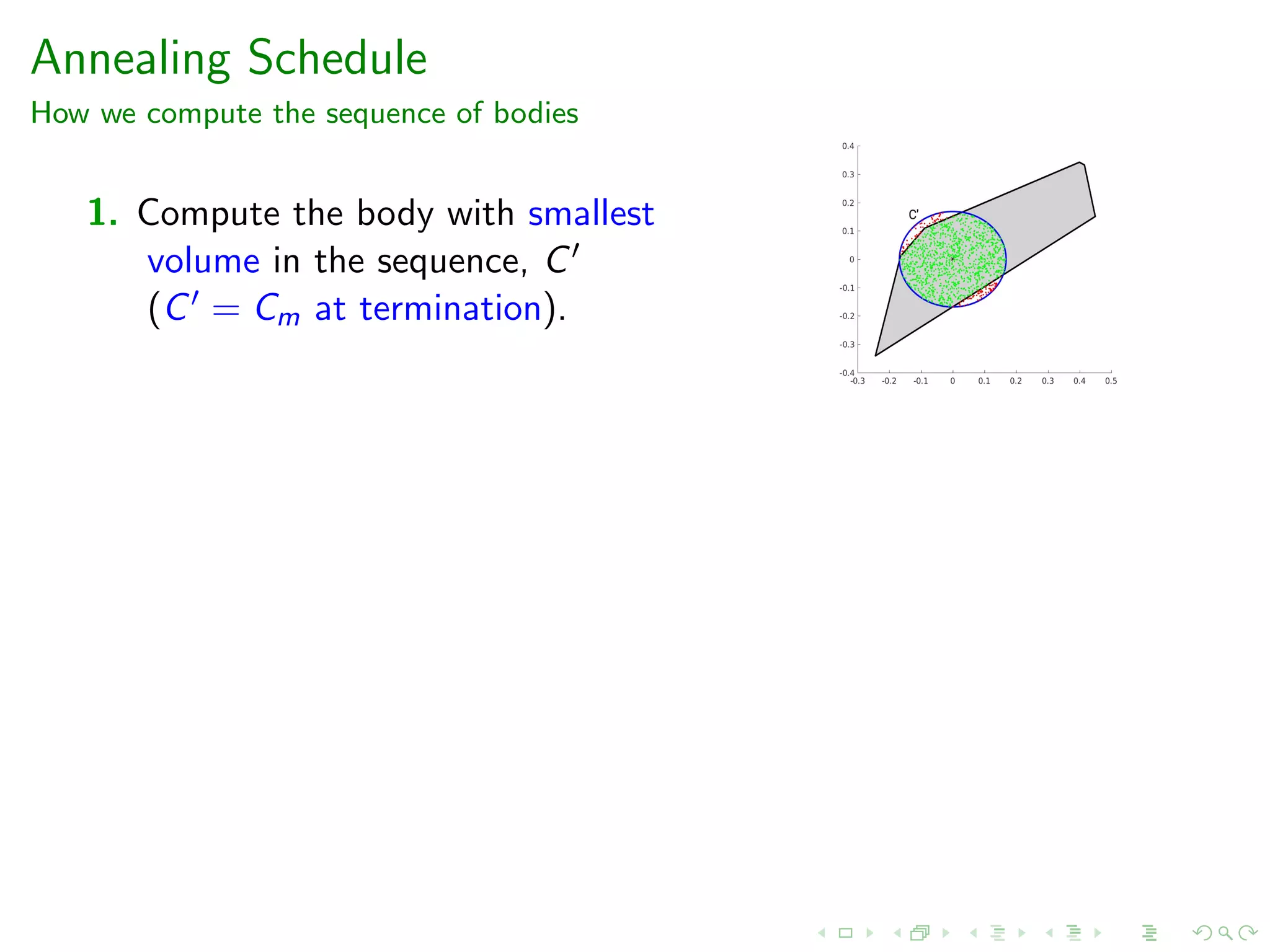

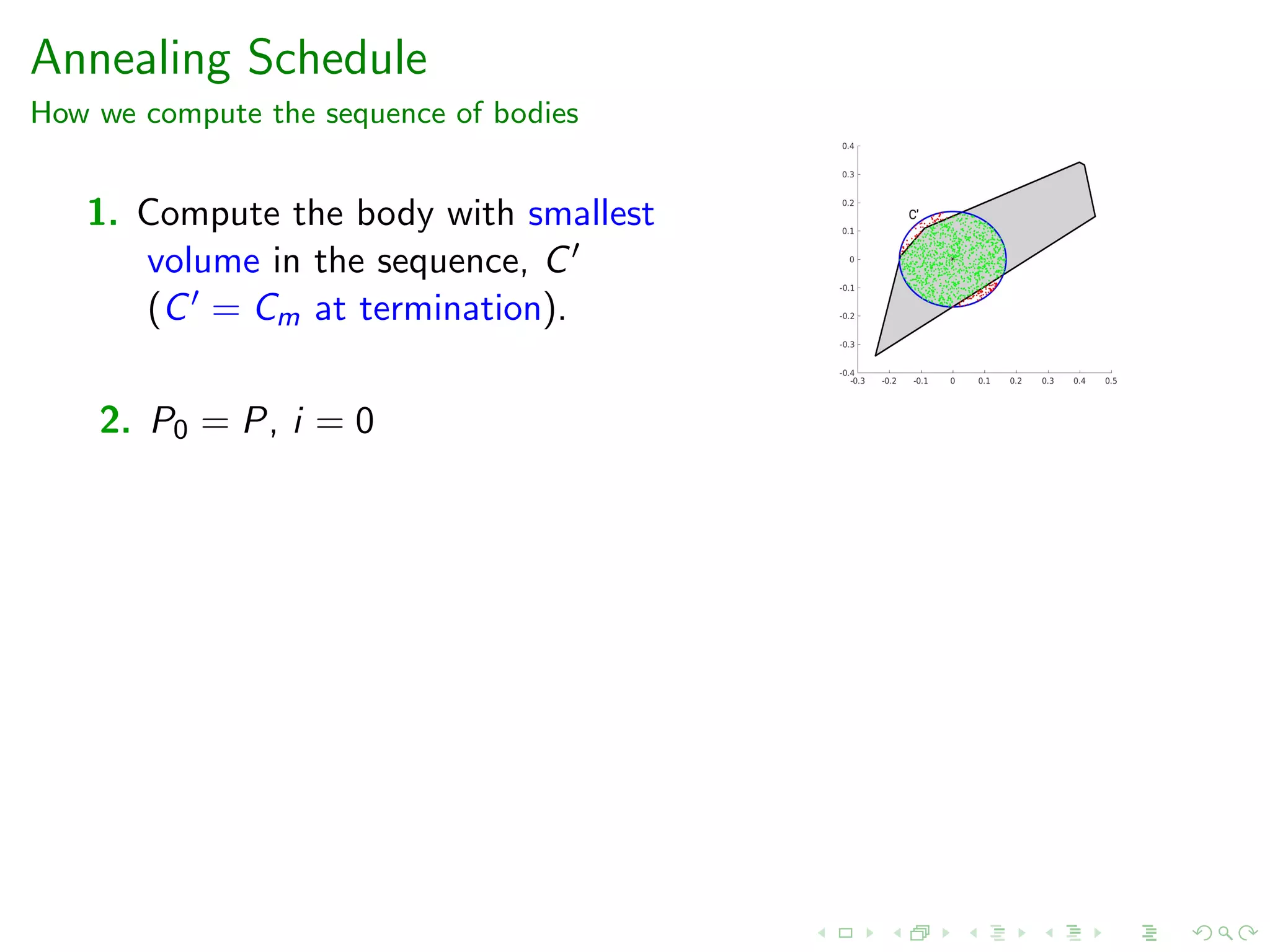

![Annealing Schedule

How we compute the sequence of bodies

1. Compute the body with smallest

volume in the sequence, C

(C = Cm at termination).

2. P0 = P, i = 0

3. if vol(C ∩ P)/vol(Pi ) ≥ r set m = i + 1, Cm = C stop

otherwise construct Pi+1 s.t. vol(Pi+1)/vol(Pi ) ∈ [r, r + δ].

Check stopping criterion Construct Pi+1](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/acac19-200326204311/75/14th-Athens-Colloquium-on-Algorithms-and-Complexity-ACAC19-42-2048.jpg)

![Annealing Schedule

How we compute the sequence of bodies

1. Compute the body with smallest

volume in the sequence, C

(C = Cm at termination).

2. P0 = P, i = 0

3. if vol(C ∩ P)/vol(Pi ) ≥ r set m = i + 1, Cm = C stop

otherwise construct Pi+1 s.t. vol(Pi+1)/vol(Pi ) ∈ [r, r + δ].

Check stopping criterion Construct Pi+1

4. i = i + 1, return to step 3.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/acac19-200326204311/75/14th-Athens-Colloquium-on-Algorithms-and-Complexity-ACAC19-43-2048.jpg)

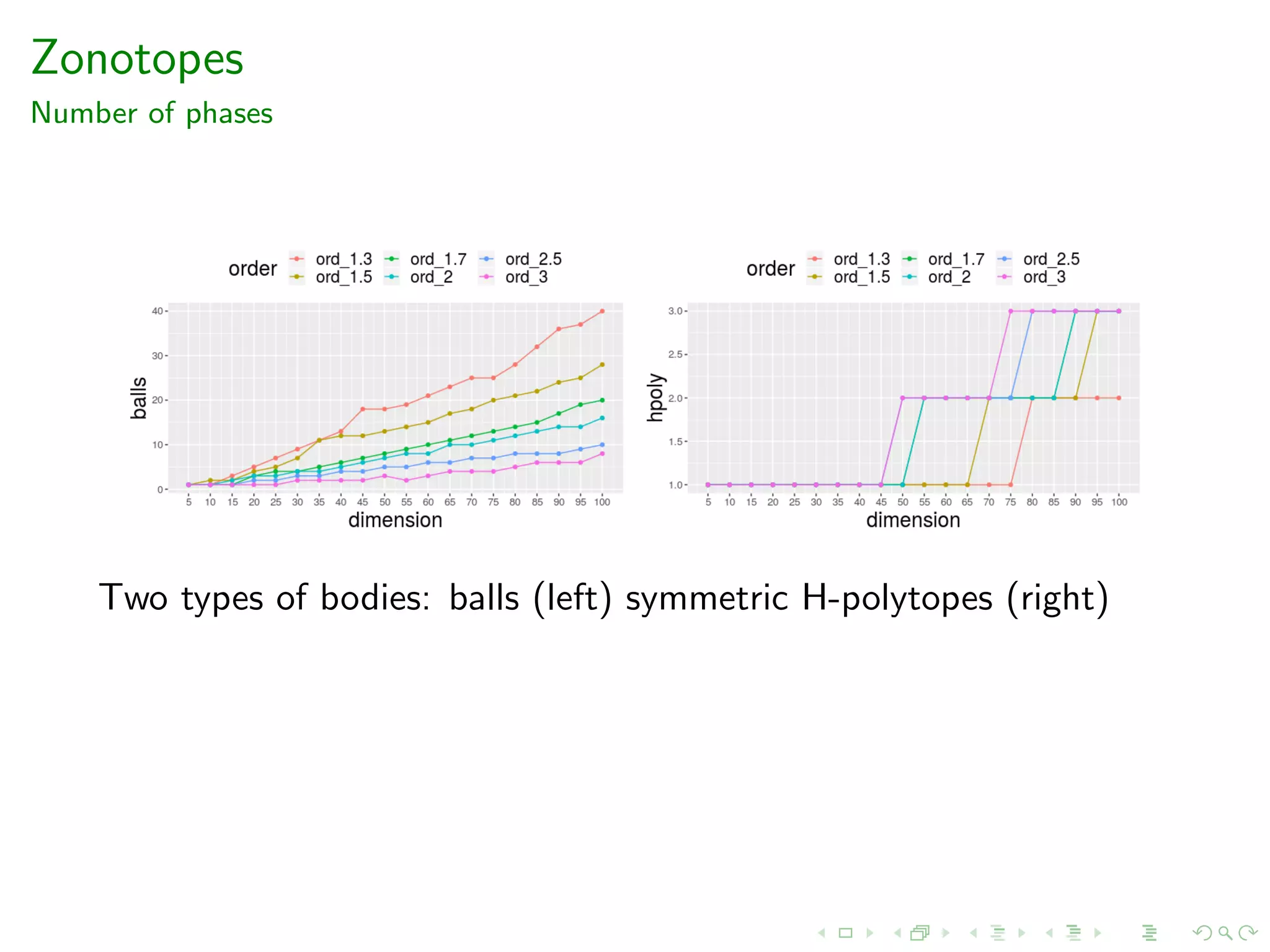

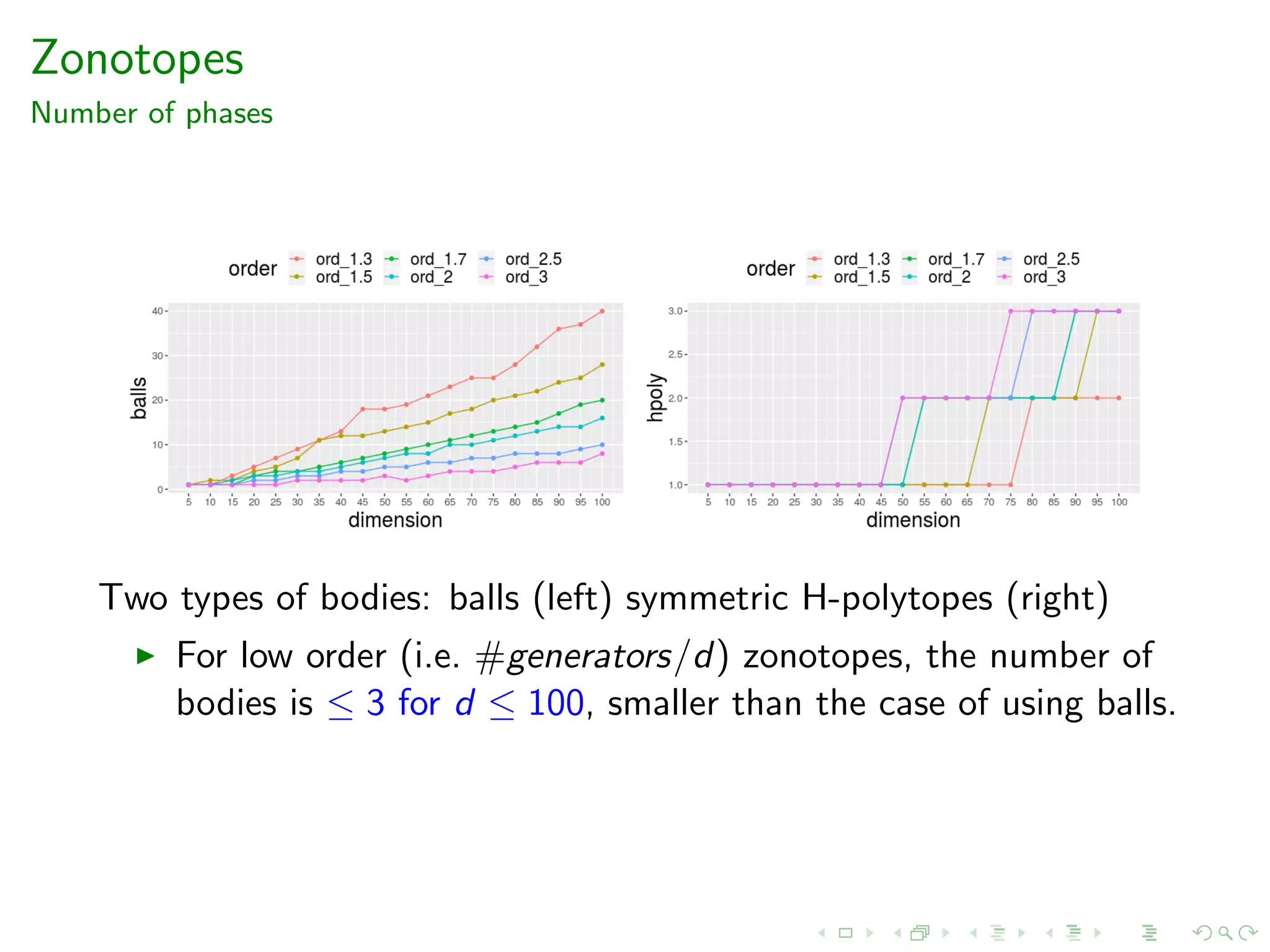

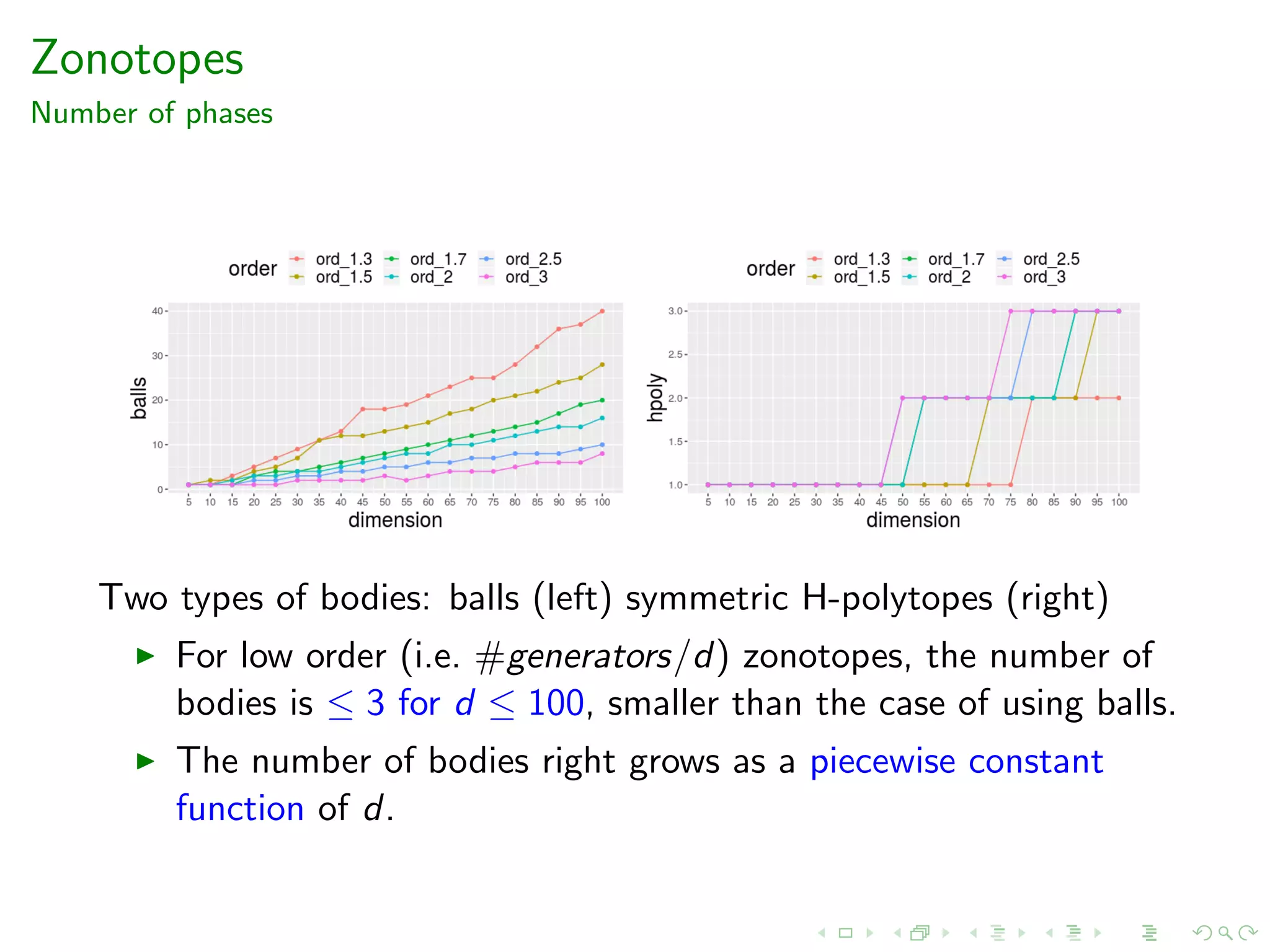

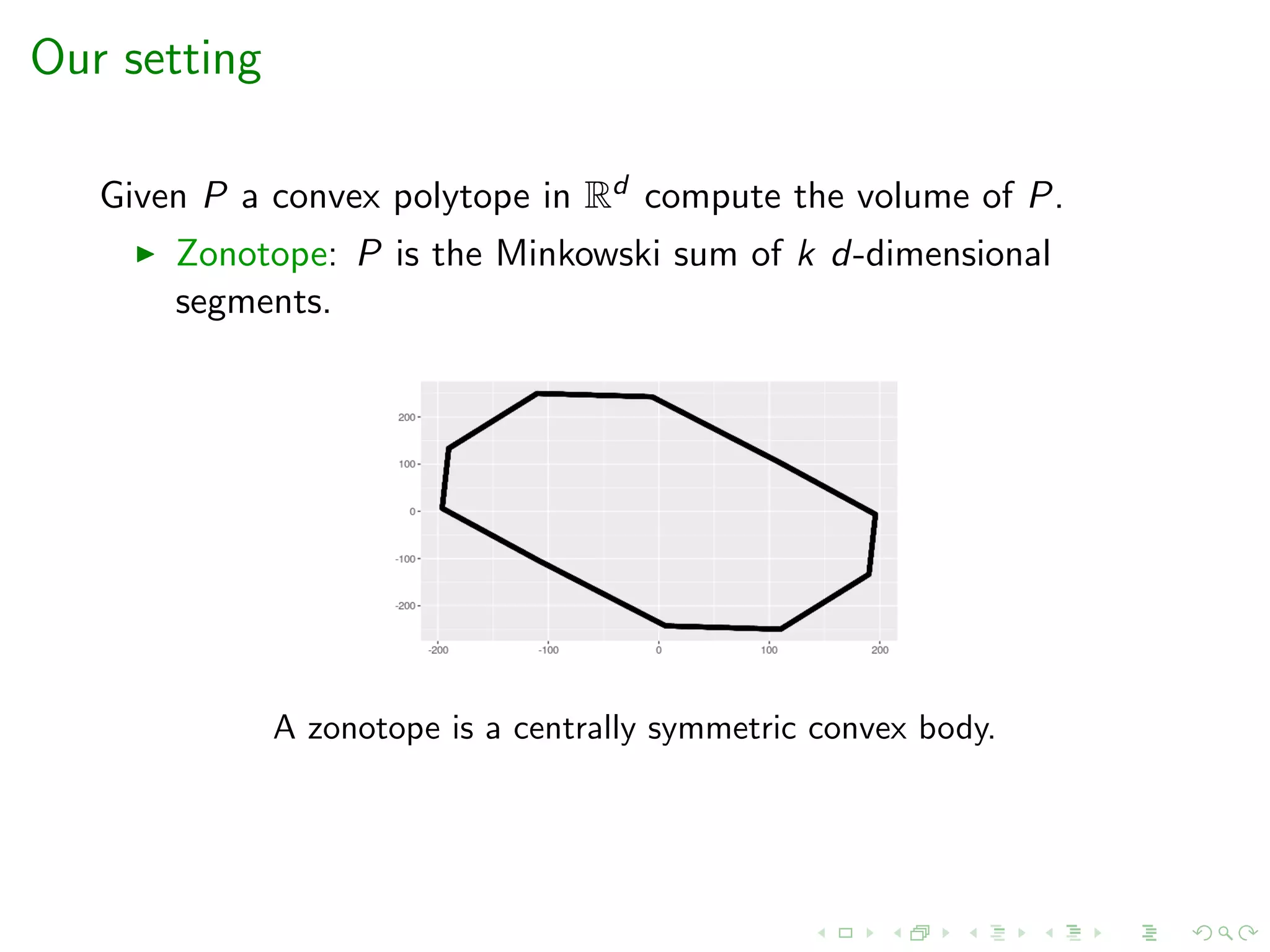

![Zonotopes

Number of phases

We use the generators of the zonotope P in order to define a

centrally symmetric H-polytope that is a ”good fit” to P.

In both figures vol(C ∩ P)/vol(C ) ∈ [0.8, 0.85].](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/acac19-200326204311/75/14th-Athens-Colloquium-on-Algorithms-and-Complexity-ACAC19-45-2048.jpg)