Sheet1BlankTemplate0Month 1Month 2Month 3Month 4Month 5Month 6Mont.docx

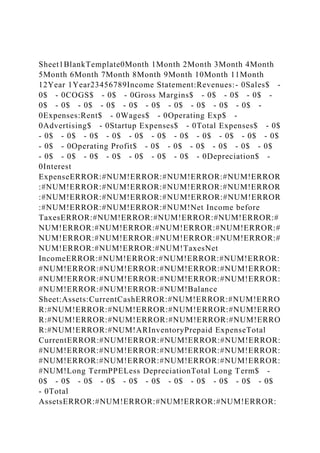

- 1. Sheet1BlankTemplate0Month 1Month 2Month 3Month 4Month 5Month 6Month 7Month 8Month 9Month 10Month 11Month 12Year 1Year23456789Income Statement:Revenues:- 0Sales$ - 0$ - 0COGS$ - 0$ - 0Gross Margins$ - 0$ - 0$ - 0$ - 0$ - 0$ - 0$ - 0$ - 0$ - 0$ - 0$ - 0$ - 0$ - 0$ - 0Expenses:Rent$ - 0Wages$ - 0Operating Exp$ - 0Advertising$ - 0Startup Expenses$ - 0Total Expenses$ - 0$ - 0$ - 0$ - 0$ - 0$ - 0$ - 0$ - 0$ - 0$ - 0$ - 0$ - 0$ - 0$ - 0Operating Profit$ - 0$ - 0$ - 0$ - 0$ - 0$ - 0$ - 0$ - 0$ - 0$ - 0$ - 0$ - 0$ - 0$ - 0Depreciation$ - 0Interest ExpenseERROR:#NUM!ERROR:#NUM!ERROR:#NUM!ERROR :#NUM!ERROR:#NUM!ERROR:#NUM!ERROR:#NUM!ERROR :#NUM!ERROR:#NUM!ERROR:#NUM!ERROR:#NUM!ERROR :#NUM!ERROR:#NUM!ERROR:#NUM!Net Income before TaxesERROR:#NUM!ERROR:#NUM!ERROR:#NUM!ERROR:# NUM!ERROR:#NUM!ERROR:#NUM!ERROR:#NUM!ERROR:# NUM!ERROR:#NUM!ERROR:#NUM!ERROR:#NUM!ERROR:# NUM!ERROR:#NUM!ERROR:#NUM!TaxesNet IncomeERROR:#NUM!ERROR:#NUM!ERROR:#NUM!ERROR: #NUM!ERROR:#NUM!ERROR:#NUM!ERROR:#NUM!ERROR: #NUM!ERROR:#NUM!ERROR:#NUM!ERROR:#NUM!ERROR: #NUM!ERROR:#NUM!ERROR:#NUM!Balance Sheet:Assets:CurrentCashERROR:#NUM!ERROR:#NUM!ERRO R:#NUM!ERROR:#NUM!ERROR:#NUM!ERROR:#NUM!ERRO R:#NUM!ERROR:#NUM!ERROR:#NUM!ERROR:#NUM!ERRO R:#NUM!ERROR:#NUM!ARInventoryPrepaid ExpenseTotal CurrentERROR:#NUM!ERROR:#NUM!ERROR:#NUM!ERROR: #NUM!ERROR:#NUM!ERROR:#NUM!ERROR:#NUM!ERROR: #NUM!ERROR:#NUM!ERROR:#NUM!ERROR:#NUM!ERROR: #NUM!Long TermPPELess DepreciationTotal Long Term$ - 0$ - 0$ - 0$ - 0$ - 0$ - 0$ - 0$ - 0$ - 0$ - 0$ - 0$ - 0Total AssetsERROR:#NUM!ERROR:#NUM!ERROR:#NUM!ERROR:

- 2. #NUM!ERROR:#NUM!ERROR:#NUM!ERROR:#NUM!ERROR: #NUM!ERROR:#NUM!ERROR:#NUM!ERROR:#NUM!ERROR: #NUM!Liabilities and Owners Equity:Liabilities:APLoan/Note$ - 0$ - 0ERROR:#NUM!ERROR:#NUM!ERROR:#NUM!ERROR:#NU M!ERROR:#NUM!ERROR:#NUM!ERROR:#NUM!ERROR:#NU M!ERROR:#NUM!ERROR:#NUM!ERROR:#NUM!Amortization - PrincERROR:#NUM!ERROR:#NUM!ERROR:#NUM!ERROR:# NUM!ERROR:#NUM!ERROR:#NUM!ERROR:#NUM!ERROR:# NUM!ERROR:#NUM!ERROR:#NUM!ERROR:#NUM!ERROR:# NUM!Net Loan$ - 0ERROR:#NUM!ERROR:#NUM!ERROR:#NUM!ERROR:#NU M!ERROR:#NUM!ERROR:#NUM!ERROR:#NUM!ERROR:#NU M!ERROR:#NUM!ERROR:#NUM!ERROR:#NUM!ERROR:#NU M!Total LiabilitiesERROR:#NUM!ERROR:#NUM!ERROR:#NUM!ERR OR:#NUM!ERROR:#NUM!ERROR:#NUM!ERROR:#NUM!ERR OR:#NUM!ERROR:#NUM!ERROR:#NUM!ERROR:#NUM!ERR OR:#NUM!Owners Equity:PIC$ - 0$ - 0$ - 0$ - 0$ - 0$ - 0$ - 0$ - 0$ - 0$ - 0$ - 0$ - 0$ - 0Retained EarningsERROR:#NUM!ERROR:#NUM!ERROR:#NUM!ERRO R:#NUM!ERROR:#NUM!ERROR:#NUM!ERROR:#NUM!ERRO R:#NUM!ERROR:#NUM!ERROR:#NUM!ERROR:#NUM!ERRO R:#NUM!Capital Stock$ - 0ERROR:#NUM!ERROR:#NUM!ERROR:#NUM!ERROR:#NU M!ERROR:#NUM!ERROR:#NUM!ERROR:#NUM!ERROR:#NU M!ERROR:#NUM!ERROR:#NUM!ERROR:#NUM!Total Owners Equity$ - 0ERROR:#NUM!ERROR:#NUM!ERROR:#NUM!ERROR:#NU M!ERROR:#NUM!ERROR:#NUM!ERROR:#NUM!ERROR:#NU M!ERROR:#NUM!ERROR:#NUM!ERROR:#NUM!ERROR:#NU M!Total Liabilities and Owners EquityERROR:#NUM!ERROR:#NUM!ERROR:#NUM!ERROR: #NUM!ERROR:#NUM!ERROR:#NUM!ERROR:#NUM!ERROR: #NUM!ERROR:#NUM!ERROR:#NUM!ERROR:#NUM!ERROR:

- 3. #NUM!Cash FlowBeginning Cash$ - 0ERROR:#NUM!ERROR:#NUM!ERROR:#NUM!ERROR:#NU M!ERROR:#NUM!ERROR:#NUM!ERROR:#NUM!ERROR:#NU M!ERROR:#NUM!ERROR:#NUM!ERROR:#NUM!$ - 0Net Income(Retained Earnings)ERROR:#NUM!ERROR:#NUM!ERROR:#NUM!ERRO R:#NUM!ERROR:#NUM!ERROR:#NUM!ERROR:#NUM!ERRO R:#NUM!ERROR:#NUM!ERROR:#NUM!ERROR:#NUM!ERRO R:#NUM!ERROR:#NUM!Change in Assets$ - 0AR$ - 0$ - 0$ - 0$ - 0$ - 0$ - 0$ - 0$ - 0$ - 0$ - 0$ - 0$ - 0$ - 0Inventory$ - 0$ - 0$ - 0$ - 0$ - 0$ - 0$ - 0$ - 0$ - 0$ - 0$ - 0$ - 0$ - 0Pre Paid Exp$ - 0$ - 0$ - 0$ - 0$ - 0$ - 0$ - 0$ - 0$ - 0$ - 0$ - 0$ - 0$ - 0PPE$ - 0$ - 0$ - 0$ - 0$ - 0$ - 0$ - 0$ - 0$ - 0$ - 0$ - 0$ - 0$ - 0$ - 0Change in Liabilities$ - 0AP$ - 0$ - 0$ - 0$ - 0$ - 0$ - 0$ - 0$ - 0$ - 0$ - 0$ - 0$ - 0$ - 0Loan/NoteERROR:#NUM!ERROR:#NUM!ERROR:#NUM!ER ROR:#NUM!ERROR:#NUM!ERROR:#NUM!ERROR:#NUM!ER ROR:#NUM!ERROR:#NUM!ERROR:#NUM!ERROR:#NUM!ER ROR:#NUM!ERROR:#NUM!Cash from Financing Equity$ - 0Cash from Financing Debt$ - 0Ending Cash$ - 0ERROR:#NUM!ERROR:#NUM!ERROR:#NUM!ERROR:#NU M!ERROR:#NUM!ERROR:#NUM!ERROR:#NUM!ERROR:#NU M!ERROR:#NUM!ERROR:#NUM!ERROR:#NUM!ERROR:#NU M!ERROR:#NUM! Sheet2DataMortgage0Interest/yr10%Term (yrs)5Compounding12Payment$0.00Starting Month1Month123456789101112131415161718192021222324Ex penses InterestERROR:#NUM!ERROR:#NUM!ERROR:#NUM!ERROR: #NUM!ERROR:#NUM!ERROR:#NUM!ERROR:#NUM!ERROR: #NUM!ERROR:#NUM!ERROR:#NUM!ERROR:#NUM!ERROR: #NUM!ERROR:#NUM!ERROR:#NUM!ERROR:#NUM!ERROR: #NUM!ERROR:#NUM!ERROR:#NUM!ERROR:#NUM!ERROR: #NUM!ERROR:#NUM!ERROR:#NUM!ERROR:#NUM!ERROR: #NUM!Ammort

- 4. PrincipalERROR:#NUM!ERROR:#NUM!ERROR:#NUM!ERRO R:#NUM!ERROR:#NUM!ERROR:#NUM!ERROR:#NUM!ERRO R:#NUM!ERROR:#NUM!ERROR:#NUM!ERROR:#NUM!ERRO R:#NUM!ERROR:#NUM!ERROR:#NUM!ERROR:#NUM!ERRO R:#NUM!ERROR:#NUM!ERROR:#NUM!ERROR:#NUM!ERRO R:#NUM!ERROR:#NUM!ERROR:#NUM!ERROR:#NUM!ERRO R:#NUM!CheckERROR:#NUM!ERROR:#NUM!ERROR:#NUM! ERROR:#NUM!ERROR:#NUM!ERROR:#NUM!ERROR:#NUM! ERROR:#NUM!ERROR:#NUM!ERROR:#NUM!ERROR:#NUM! ERROR:#NUM!ERROR:#NUM!ERROR:#NUM!ERROR:#NUM! ERROR:#NUM!ERROR:#NUM!ERROR:#NUM!ERROR:#NUM! ERROR:#NUM!ERROR:#NUM!ERROR:#NUM!ERROR:#NUM! ERROR:#NUM! Sheet3 7/30/2019 Print https://content.ashford.edu/print/Schneider.4937.17.1?sections= navpoint-1,navpoint-7,navpoint-8,navpoint-9,navpoint- 10,navpoint-11,navpoint-12,na… 1/93 7/30/2019 Print https://content.ashford.edu/print/Schneider.4937.17.1?sections= navpoint-1,navpoint-7,navpoint-8,navpoint-9,navpoint- 10,navpoint-11,navpoint-12,na… 2/93 LearningObjectives After studying Chapter 1, you will be able to: Distinguish between �inancial accounting and managerial

- 5. accounting. Recognize the primary roles and ethical responsibilities of the management accountant. De�ine, distinguish, and illustrate key cost concepts. Understand the differences in cost �lows among service, merchandising, and manufacturing enterprises. Distinguish between the behavior of variable and �ixed costs and formulate cost functions. Understand cost terms relating to planning and control. 1 Managerial Accounting and Cost Concepts DragonImages/iStock/Thinkstock 7/30/2019 Print https://content.ashford.edu/print/Schneider.4937.17.1?sections= navpoint-1,navpoint-7,navpoint-8,navpoint-9,navpoint- 10,navpoint-11,navpoint-12,na… 3/93 Introduce the concept of contribution margin and its variations. TheController’sWorkDay:WhereDidtheTimeGo? It’s early October. Mary Rosen, Controller of Herschel Software Products, has just arrived at her of�ice at about 7:30 a.m. She scans her email messages, checks

- 6. her electronic calendar, and looks through her in-basket. She says, “Wow, another ‘normal’ day!” She wonders if she’ll make her tennis date with her husband at 6 p.m. Her calendar shows: 9:00 Meet with division head of Customer Support to discuss next year’s budget numbers. Review preliminary budget numbers before meeting. 10:00 Meet with accounting systems analysts to discuss status of a project to improve the �irm’s monthly management “plan versus actual” reporting system. 11:30 Hold a quick session with Marketing Vice-President, Gary Martin, to discuss pricing negotiations with new customer. 12:15 Have working lunch with corporate attorney to discuss customer contract wording for a new product being introduced early next year. 2:00 With budget manager, review September’s actual results and budget comparisons and identify problem areas. Also, review third quarter results before her presentation to the President at Friday’s staff meeting. 4:00 Review a special cost-volume-pro�it study of Herschel Software Products, relative to the �irm’s strategic plan’s pro�itability goals. Mary also knows that she needs to: Respond to four email questions about product costs and operating expenses. Talk to Steve Simcha, New Product Development Vice-

- 7. President, about a serious cost- overrun problem with a new product project. Prepare a presentation on cash �lows for the �irm’s strategic planning meeting next month. Write a memo supporting the spending of $100,000 by the Marketing Vice-President on media contracts. Every meeting, discussion, and decision that Mary has today, and every day, uses accounting information. She must generate relevant data in the right form and at the right time. She and her fellow managers must understand cost behavior, cost/bene�it analyses, plan versus actual comparisons, and how to use information to achieve Herschel Software Products’ long-term and short-term goals. 7/30/2019 Print https://content.ashford.edu/print/Schneider.4937.17.1?sections= navpoint-1,navpoint-7,navpoint-8,navpoint-9,navpoint- 10,navpoint-11,navpoint-12,na… 4/93 Managers make decisions. Managers select one or more alternatives from a set of choices. Making the best choice depends on the manager’s goals, the expected results from each alternative, and the information available when the decision is made. Decision-making information is the focus of this text. Collecting, classifying, reporting, and analyzing relevant information are fundamental to every action that managers take. Management accountants prepare information for decision makers. In this chapter, the stage is set

- 8. for discussing how management accountants are involved in decision making. First, we discuss the distinction between �inancial and managerial accounting. 7/30/2019 Print https://content.ashford.edu/print/Schneider.4937.17.1?sections= navpoint-1,navpoint-7,navpoint-8,navpoint-9,navpoint- 10,navpoint-11,navpoint-12,na… 5/93 1.1TheDualRolesofAccountingInformation The accounting system generates the information that satis�ies two reporting needs that coexist within an organization: �inancial accounting and managerial accounting. Figure 1.1 shows the primary interested parties and the typical reports generated to serve these two user groups. Figure1.1:Scopeof�inancialandmanagerialaccounting FinancialAccounting Financialaccounting is the branch of accounting that organizes accounting information for presentation to interested parties both inside and outside of the organization. The primary �inancial accounting reports are the balance sheet (often called a statement of �inancial position), the income statement, and the statement of cash �lows. The balance sheet is a summary of assets, liabilities, and shareholders’ equity at a speci�ied point in time. The income statement reports revenues and expenses resulting from the company’s operations for a particular time period. The statement of cash �lows shows the sources and

- 9. uses of cash over a time period for operating, investing, and �inancing activities. Most businesses are complex, and guidelines (known as generally accepted accounting principles or GAAP) are provided for �inancial reporting. The Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB), the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), and the Public Company Accounting Oversight Board (PCAOB) oversee the development of these principles, corporate �inancial reporting responsibilities, and internal control standards. Internationally, while some countries have developed their own accounting principles, many countries have adopted standards set by the International Accounting Standards Board (IASB). Owners,Investors,andCreditors Shareholder-owned �irms rely heavily on owners, investors, and creditors (providers of short-term credit and long-term loans) for sources of capital. Shareholders and investors use accounting reports to decide 7/30/2019 Print https://content.ashford.edu/print/Schneider.4937.17.1?sections= navpoint-1,navpoint-7,navpoint-8,navpoint-9,navpoint- 10,navpoint-11,navpoint-12,na… 6/93 whether to buy, sell, or hold the �irm’s stock. Also, creditors assess whether the �irm is able to pay its debts on time. TaxingAuthorities

- 10. The assessment of many taxes is based on accounting information submitted by the taxpayer. Examples of such taxes include income taxes, sales taxes, use taxes, franchise taxes, excise taxes, property taxes, and gift and estate taxes. In most cases, the dominant taxing authority is the federal government and its tax collection agency, the Internal Revenue Service. RegulatoryAgencies Local, state, and federal agencies regulate a substantial portion of business activity in the United States. Much regulation is implemented through or involves accounting reports. IndustryAssociations Most industries have an association that gathers important statistics about the national and international industry. A large part of the information they provide comes from accounting reports provided by member �irms. Examples include corporate annual reports, call reports for banks, and auto dealership sales reports. ManagersandEmployees Managers typically have direct vested interests in their �irms’ results. Performance bonuses, stock options, and incentive compensation programs are common. Thus, managers are not passive observers as to how certain transactions are recorded. Firm policies, performance evaluation methods, and compensation systems should encourage managers to act in the best interests of themselves and the �irm as a whole. The �irm’s executives are responsible to the board of directors and shareholders for the �irm’s �inancial results. Numerous examples of changes in high-level executive

- 11. positions reaf�irm the importance of achieving strong pro�its to remain in power and employed. Based in part on �inancial statement information, employees make decisions about continued employment, union wage demands and contract negotiations, adequacy of pension plans, and employee stock purchase or savings plans. Pro�it sharing may encourage employees to want the company to be �inancially successful. ManagerialAccounting Managerialaccounting is the branch of accounting that meets managers’ information needs. Whereas �inancial accounting has a backwards focus, i.e., focusing on historical information, managerial accounting focuses more on the future. Because managerial accounting is designed to assist the �irm’s managers in making business decisions, relatively few restrictions are imposed by regulatory bodies and generally accepted accounting principles. Therefore, a manager must de�ine which data are relevant for a particular purpose and which are not. DifferencesBetweenManagerialandFinancialAccounting 7/30/2019 Print https://content.ashford.edu/print/Schneider.4937.17.1?sections= navpoint-1,navpoint-7,navpoint-8,navpoint-9,navpoint- 10,navpoint-11,navpoint-12,na… 7/93 Several important differences distinguish managerial accounting from �inancial accounting. First,

- 12. managerial accounting is not subject to the same rules and principles as is �inancial accounting. In many cases, “common sense” is the most important guide for decision makers. A second difference is that �inancial accounting relies on accounting principles structured around the accounting equation. Management reports, on the other hand, are designed to meet managers’ needs. These reports often use estimates and forecasts, use different values for the same events, do not balance in a debit/credit sense, and are designed for particular decisions or analyses. The expression “different costs for different purposes” has long been used to describe relevance. Relevant information has an impact on the decision analysis. Irrelevant data have no impact. Another difference is that managerial accounting focuses on segments of the organization as well as on the whole organization. The primary interest of �inancial accounting is the company as a whole. In managerial accounting, however, the segment is of major importance. Segments may be products, projects, divisions, plants, branches, regions, or any other subset of the business. Tracing or allocating costs, revenues, and assets to segments creates dif�icult issues for managerial accountants. Two important similarities do exist. The same transaction and accounting information systems are used to generate the data inputs for both �inancial statements and management reports. Therefore, when the system accumulates and classi�ies information, it should do so in formats that accommodate both types of accounting. The other similarity is the manner in which accountants measure costs, de�ine assets, and

- 13. specify accounting periods. Many concepts underlie accounting information, whether the data are later used for �inancial or managerial reporting. Recording the results of events is often based on rationales that are common to both �inancial and managerial accounting. We must understand what is a common thread and what must be independently collected. 7/30/2019 Print https://content.ashford.edu/print/Schneider.4937.17.1?sections= navpoint-1,navpoint-7,navpoint-8,navpoint-9,navpoint- 10,navpoint-11,navpoint-12,na… 8/93 1.2RoleoftheManagementAccountant Although the top accounting-oriented people in an organization are the chief �inancial of�icer and the controller, the accounting and �inancial management functions contain a range of jobs. A variety of careers is available as shown in Figure 1.2; these careers can frequently be paths to executive management. Figure1.2:Managementaccountingjobtitles A management accountant maintains accounting records, prepares �inancial statements, generates managerial reports and analyses, and coordinates budgeting efforts. The management accountant is an advisor, an internal consultant, and an integral part of management. The controller is responsible for managing the entire accounting function. The controller in�luences management by answering questions like: What information should be reported? What format best displays the information? How can data be

- 14. collected and processed? By the nature of the job, the management accountant applies management principles and often is a major player in decision making itself. Certi�iedManagementAccountant The Certi�ied Management Accounting program recognizes a person’s achievement of a speci�ic level of knowledge and professional skill. Becoming a Certi�iedManagementAccountant (CMA) is considered an important professional step for anyone desiring to become a management accounting or �inancial executive. The CMA program was founded on the principle that a management accountant is a contributor to and a participant in management. To qualify for the CMA designation, candidates must pass a comprehensive examination and meet speci�ic educational and professional standards and experience requirements. To remain a CMA, a person must meet continuing educational requirements and adhere to the program’s “Statement of Ethical Professional Practices.” The Institute of Management Accountants (IMA) is the professional organization of management accountants and sponsors the CMA designation. EthicalConductofManagementAccountants Earlier in the chapter, we discussed managers’ needs for accounting information. We assumed that whatever information the accounting system generates is presented and used in an ethical manner. Ethical 7/30/2019 Print

- 15. https://content.ashford.edu/print/Schneider.4937.17.1?sections= navpoint-1,navpoint-7,navpoint-8,navpoint-9,navpoint- 10,navpoint-11,navpoint-12,na… 9/93 conduct is a necessary asset of a managerial accountant. The credibility of the information provided, analyses done, and opinions offered depends heavily on the reputation of the responsible accountant. Independence, competence, lack of bias or favoritism, trust, and objectivity are key elements in establishing credibility. While true for all managers, management accountants in particular must maintain integrity and ethical behavior and must make top management aware of unethical behavior on the part of others within the organization. This does not mean the management accountant is a police of�icer. Rather, the management accountant promotes and encourages ethical behavior in all aspects of business life. Ethical standards of businesspersons have been given much more visibility and scrutiny in recent years. Issues that appear again and again in management careers test the ethical standards of everyone. Among common ethical issues are: Businesspracticesandpolicies. Practices that seem harmless on the surface may encourage or require employees or managers to be deceitful or dishonest. Objectivereporting. Because situations exist where prejudiced reporting of certain numbers may in�luence decisions, accountants are guided by goals of unbiased reporting and professional judgment.

- 16. Colleaguebehavior. Even if we have high ethical standards, people around us may not be so disposed. Many policies and internal controls are in place in organizations to prevent wrongdoing and to encourage proper behavior. In addition, you should not compromise your personal integrity by condoning unethical behavior in others. Competitors. Winning is part of the business “game.” But to do so in a fair environment is critical. Using true product and competitor data; following corporate policies; and abhorring bribes, kickbacks, and other similar payments are easy examples. Many �irms provide behavior guidelines and policies to purchasing and sales personnel who are at particular risk in giving and receiving favors and improper inducements. Taxavoidanceandevasion. Tax burdens can be signi�icant. Proper planning and careful use of tax laws to minimize the organization’s tax liability are acceptable. Tax avoidance is legitimate. Inappropriate use of the same laws or use of deceit to hide income or overstate deductions is tax evasion, which is unethical as well as illegal. Con�identiality. Internal data are developed for managers’ use. Disclosures outside the �irm often require review and approvals. Privacy of competitive, personnel, and negotiating data is critical. Negative examples of overheard conversations in elevators, on golf courses, and at lunches that lead to lost business, embarrassment, and lawsuits are unfortunately common. Con�identiality also demands that “insider” information should not be used for anyone’s personal advantage. Appearanceofindependence. The accountant should be independent in situations where the resulting information is used for analysis and decision making.

- 17. Independence applies to both actual independence and the appearance of independence. If it appears that the management accountant is biased because of that person’s conduct, associations, or vested interests (possible promotion, salary increases or bonuses, or investments), the information provided is tainted and open to doubt by other decision makers. Corporateloyaltyandpersonaladvancement. Many situations exist in which, because of an unethical act, the reputation of the �irm itself is in danger. Alternately, an unethical act may seem to ensure your personal enhancement in some manner. Sometimes reporting an unethical act will endanger the future of the person reporting the act. These are all dif�icult dilemmas, pitting right against wrong, and not always in an obvious way. 7/30/2019 Print https://content.ashford.edu/print/Schneider.4937.17.1?sections= navpoint-1,navpoint-7,navpoint-8,navpoint-9,navpoint- 10,navpoint-11,navpoint-12,n… 10/93 While space and time do not allow us to develop approaches for resolving these problems here, it is clear that ethical issues underlie management accountants’ professional and day-to-day activities. Each person must develop a method of handling ethical problems. Of primary importance is the ability to see an ethical dilemma when it faces us. Once identi�ied, the situation may cause us to request advice. Numerous sources are available for guidance, including:

- 18. Personalvalues. We would like to think that our own value system is “ethical” and provides enough guidance. Clearly, this is our main line of defense against “wrong.” Corporatepoliciesandethicsstatements. Many �irms have statements on expected employee behavior or written policies and procedures on how a range of situations should be handled. These statements do set limits or barriers and may describe expected levels of behavior. Some companies also offer ethics seminars and classes to their employees. Laws. “If it’s legal, it must be okay” is often used a basis for de�ining ethical behavior. This is absolutely not true. Laws are developed in a political process, often without much serious consideration for the ethical conduct of any parties involved. It’s highly probable that if the behavior is illegal, it is also unethical. Professionalstandards. Most professions have developed a statement of ethical standards for their members. Figure 1.3 presents a statement developed for management accountants. These statements are basic standards of behavior and give professional guidance in many areas. Supervisors,internalauditors,andothercompanyof�icials. These are often persons with more experience and broader understanding of con�licting issues and of corporate attitudes. An ethical situation, however, may involve a supervisor or other corporate of�icial, which may make the dilemma much more sensitive and severe. A few companies have created an ombudsperson position to assist employees in handling delicate situations. Counselorsfromoutsideoftheorganization. This is a last resort and generally violates

- 19. another ethical consideration—con�identiality. While close friends, a spouse, or a personal counselor may seem like logical sources of advice and support, the nature of the dilemma may require con�identiality until all other avenues of resolution are exhausted. Merely consulting outsiders presents serious risks of unauthorized disclosure that may only further complicate an issue. Even though all of these options may exist, we each need to develop a rational approach to identifying, analyzing, and deciding on ethical issues that confront us. Management accountants must be aware of ethical dilemmas, perhaps more than the typical manager, because of their responsibility for decision- making information and their involvement in many decision- making processes. The Institute of Management Accountants believes ethics is a cornerstone of its organization and recognizes the importance of providing ethical guidance. The IMA has developed Standards of Ethical Professional Practice. That statement is presented in Figure 1.3. The Standards are broken into four sections: competence, con�identiality, integrity, and credibility. Competence refers to the skills that the accountant brings to the job. Con�identiality is de�ined as protecting the access to and use of information. Integrity focuses primarily on the personal behavior and interactions of the management accountant. Credibility, as de�ined here, is primarily directed toward disclosure of unbiased information. Figure1.3:InstituteofManagementAccountants’Standardsof EthicalProfessionalPractice

- 20. 7/30/2019 Print https://content.ashford.edu/print/Schneider.4937.17.1?sections= navpoint-1,navpoint-7,navpoint-8,navpoint-9,navpoint- 10,navpoint-11,navpoint-12,n… 11/93 IMA(InstituteofManagementAccountants).Reprintedwithpermiss ion. UsingCostInformation Much of managerial accounting deals with cost information. Understanding cost behavior and knowing which costs to consider and which to ignore are critical to making decisions in business and in everyday life situations. Managers use cost information in many different ways. Cost data are especially important in these areas: Planning. Estimating future costs in preparing budgets and in projecting operating activities. Decisionmaking. Considering costs relevant to a wide variety of decision-making processes. Costcontrol. Measuring costs incurred; comparing these costs with budgets, goals, targets, or standards; and evaluating differences or variances. Incomemeasurement. Determining the costs of products and services sold to determine this time period’s pro�itability for the entire business or some segment of the business, such as a contract, a product, or a customer.

- 21. 7/30/2019 Print https://content.ashford.edu/print/Schneider.4937.17.1?sections= navpoint-1,navpoint-7,navpoint-8,navpoint-9,navpoint- 10,navpoint-11,navpoint-12,n… 12/93 1.3TheNatureofCost Cost, broadly de�ined, is the amount of resources given up to gain a speci�ic objective or object. Generally, cost refers to the monetary measurement (exchange price) attached to acquiring goods and services consumed by some activity. A cost need only be incurred and not necessarily be paid for it to be considered a cost. Cash outlays are monetary measurements; occasionally, goods and services are also obtained by exchanging other assets, such as receivables or property, or by taking on debt. A costobject is de�ined as anything for which one accumulates costs. A cost object is the reason for making decisions, costing products, planning spending levels, or evaluating actual performances. It is the “why” of cost analysis. Business people undertake activities to achieve some output or result. Often these activities incur costs— purchasing materials, hiring people, and renting space—and are known as costdrivers. Determining a product’s cost involves �inding the cause-and-effect connection between inputs and outputs. A cost driver links activities that create outputs with the inputs that are used. Figure 1.4 presents the fundamental relationship among resources, activities, and products. Activities are at the core of all we do in business. Activities drive the use of resources; from the activities, come

- 22. products. This is the traditional input-to-output cycle, understanding that work is done in the middle box of Figure 1.4—meaning tasks are performed with labor, machines, or hired resources. Costs are incurred by cost drivers and are assigned to the products. These linkages will be used over and over as we progress through our costing analyses to aid decision making, particularly in Chapter 9. Figure1.4:Activity-centeredcostingrelationships Cost, in many respects, is an elusive term. Cost has meaning only for a particular purpose and situation. Consequently, meaningful use of the term cost requires an adjective—such as incremental, average, or avoidable—to de�ine its use. Each adjective indicates certain attributes, and those attributes dictate the relevance of each cost. Since costs are resources given up to obtain a speci�ic good or service, that good or service may be consumed or it may still be an asset at the end of an accounting period. In many managerial analyses, the distinction among cost, expense, and asset is clouded. The words cost and expense are used interchangeably, as is done throughout this text. Yet for pro�it measurement, cost dollars imply assets, and expenses are subtracted from revenues. 7/30/2019 Print https://content.ashford.edu/print/Schneider.4937.17.1?sections= navpoint-1,navpoint-7,navpoint-8,navpoint-9,navpoint- 10,navpoint-11,navpoint-12,n… 13/93

- 23. 1.4ComparingService,Merchandising,andManufacturingOrganiz ations Many similarities exist when we compare service, merchandising, and manufacturing organizations. Providing a service to a client in a law �irm or repairing a washing machine in a �ix-it shop have strong similarities to manufacturing automobiles in spite of different physical and business settings. In service industries, resources are brought together to provide the service, just as they are brought together to create a product in a factory environment. Differences in measuring pro�its are largely a function of inventoried costs. Service �irms have only supplies inventories. Merchandising �irms buy and sell products and hold merchandise inventories. Manufacturing �irms buy materials and convert these inputs into saleable products. Inventories here include materials, work in process inventory (partially complete products), and �inished goods inventory (completed and ready-to-sell products). Figure 1.5 compares income statements and selected balance sheet accounts for the three business types. Figure1.5:Measuringincomeinservice,merchandising,and manufacturing�irms 7/30/2019 Print https://content.ashford.edu/print/Schneider.4937.17.1?sections= navpoint-1,navpoint-7,navpoint-8,navpoint-9,navpoint- 10,navpoint-11,navpoint-12,n… 14/93

- 24. ServiceOrganizations A service organization performs a business activity for a fee. Costs of performing the service may include salaries of professionals and support personnel, supplies, purchased services, and routine costs such as rent and utilities. In Figure 1.5, the expenses of Kalwerisky Consultants, a public relations �irm, are reported as either direct client expenses or operating expenses. Some service organizations report all expenses as operating expenses. Essentially, all operating costs incurred by the �irm are periodcosts; they become expenses of the time period in which the costs are incurred. Receivables, payables, supplies, depreciation, and perhaps costs not yet billed to clients would cause accrual net income to differ from operating cash �low. In a service organization, the problems of measuring performance, such as the pro�itability of speci�ic contracts, and matching direct costs with speci�ic revenues are surprisingly similar to manufacturing cost analyses. 7/30/2019 Print https://content.ashford.edu/print/Schneider.4937.17.1?sections= navpoint-1,navpoint-7,navpoint-8,navpoint-9,navpoint- 10,navpoint-11,navpoint-12,n… 15/93 Internally, �inancial reports for service �irms often separate revenues and expenses by type of service or customer. For example, hospitals track revenues by procedure type and attempt to measure costs of those procedures. Professional �irms, such as accountants, lawyers,

- 25. and architects, measure the direct costs of performing services by client. Lawyers record time spent on each case, both for billing purposes and for tracing salary costs. In Figure 1.5, Kalwerisky Consultants apparently serves multiple clients and can identify professional time, service costs, and other traceable costs with speci�ic client contracts. MerchandisingOrganizations A merchandising business purchases products for resale. Generally, a merchandising �irm is a link in the physical distribution chain, acting as a wholesaler or retailer. Figure 1.5 presents cost of goods sold on the income statement of Burch�ield Supermarket, a retail grocery store. Again, comprising the reported totals are detailed revenues and costs of sales for various segments, such as produce, hardware, meat, and grocery departments. Merchandise costs are inventoriable or product costs, meaning that they are an asset until sold, after which they become cost of goods sold. All other expenses in the supermarket operation are treated as period costs. ManufacturingOrganizations Manufacturing generally occurs in a factory, de�ined as a place where resources are brought together to produce a product. Examples include: Soft-drink bottling company—mixing batches and �illing bottles of root beer University cafeteria—preparing and serving food Print shop—printing a variety of items such as brochures, booklets, and business cards Breakfast cereal manufacturer—processing grains into cereal

- 26. Automotive assembly plant—joining parts and subassemblies to create a minivan But, you can see how many service �irms really do “produce” the service using our de�inition of a factory. Landscaping company—cutting lawns and planting Pharmacy—�illing prescriptions Tax return preparation �irm—preparing tax returns Hospital surgery department—performing heart bypass operations As Figure 1.5 illustrates, manufacturing �irms have more complexity in determining cost of goods sold. A new portion of the income statement, costofgoodsmanufactured, is introduced. It includes: The costs of inputs to the manufacturing process: direct materials, direct labor, and manufacturing overhead Direct materials inventory and work in process inventory needed for factory activities The sum of the product inputs, manufacturing costs for the period, is called totalmanufacturingcosts. Figure 1.6 illustrates a simpli�ied version of the Holbrook Products factory. Here resources are brought together for producing aircraft components. An assembly line in the factory is the focus of “manufacturing” activities. 7/30/2019 Print

- 27. https://content.ashford.edu/print/Schneider.4937.17.1?sections= navpoint-1,navpoint-7,navpoint-8,navpoint-9,navpoint- 10,navpoint-11,navpoint-12,n… 16/93 Materials (primarily parts and components) are purchased for production, and factory employees work to convert parts into �inished products. Many support services are used, and manufacturing overhead costs are incurred for materials handlers, equipment maintenance people, heat, power, employee bene�its, factory accountants, supervisors, and depreciation on equipment and the building. Figure1.6:TheHolbrookProductsfactory In Figure 1.6, the business is divided into of�ice and factory areas. Obviously, this example is simpli�ied and avoids many business complexities. But, it shows: Productandperiodcosts. Any cost incurred in the manufacturing process is a manufacturing cost, an inventoriable cost, and a product cost. Any cost not involved in the manufacturing process is a nonmanufacturing cost, a noninventoriable cost, and a period cost. Whereas the product costs are treated as inventory until sold, the period costs are treated as expenses immediately or as noninventory assets such as of�ice supplies. Locationofinventories. Manufacturing requires three production inventories: materials, work in process, and �inished products. Materials purchases are received and stored in the materials warehouse, and their costs recorded in MaterialsInventory. When materials are sent to the factory �loor, direct materials costs are transferred to WorkinProcessInventory, which is

- 28. production that is started but not completed. Completed products are physically sent to the �inished goods warehouse; their work in process costs are moved to FinishedGoodsInventory, which are products that are ready for sale to customers. When a sale occurs and is shipped, �inished goods product costs are moved to CostofGoodsSold, an expense account. Flowofcostsandproducts. Figure 1.6 assumes an assembly process, but many different production systems exist. Materials are added, workers process, and other activities support; a physical �low and a cost �low coexist. Figure 1.7 compares a factory to a large bucket. When the whistle blows to start the production period, the bucket already has resources in it—beginning work in process inventory. During the period, more resources are poured into the bucket—total manufacturing costs (direct materials used, direct labor, and 7/30/2019 Print https://content.ashford.edu/print/Schneider.4937.17.1?sections= navpoint-1,navpoint-7,navpoint-8,navpoint-9,navpoint- 10,navpoint-11,navpoint-12,n… 17/93 manufacturing overhead). Flowing out of the bucket are all products that are �inished during the period and added to �inished goods inventory. The cost transferred out is called cost of goods manufactured. When the whistle blows to end the period, ending work in process inventory remains in the bucket.

- 29. Figure1.7:Thefactoryasa“bucket”ofcosts To illustrate the determination of cost of goods manufactured, suppose work in process inventory of Metz Corporation changed from $21,000 to $23,500 during November. Costs incurred during November were $42,000 for direct materials used, $33,000 for direct labor, and $51,000 for manufacturing overhead. The cost of goods manufactured for November is determined as follows: Direct materials used $42,000 Direct labor 33,000 Factory overhead 51,000 Total manufacturing costs $126,000 + beginning work in process 21,000 – ending work in process (23,500) Cost of goods manufactured $123,500 Note that cost of goods manufactured represents the cost of those goods that were �inished during November. Since $21,000 of costs was incurred prior to November, it must be added to the $126,000 in costs that were incurred during November. Ending work in process of $23,500 must be deducted from the costs incurred during November because this amount represents costs for goods that have not yet been �inished, and the cost of goods manufactured includes only costs pertaining to �inished goods.

- 30. 7/30/2019 Print https://content.ashford.edu/print/Schneider.4937.17.1?sections= navpoint-1,navpoint-7,navpoint-8,navpoint-9,navpoint- 10,navpoint-11,navpoint-12,n… 18/93 TraditionalGroupingsofProductCosts Figure 1.5 illustrates the income measurement for Holbrook Products. Product cost accounting combines three groups of manufacturing costs: direct materials, direct labor, and manufacturing overhead. While automated manufacturing and cost systems can utilize many more or fewer cost groups, these three have historically been used in nearly all manufacturing costing. Directmaterialscosts are costs of physical components of the product. The range of materials includes natural resources, such as oil, grain, or lumber, and partially processed components (another company’s �inished product). Often, a complete list of all materials used in a product is prepared and is called a billof materials. A materials requisition form is used as authorization to transfer direct materials out of the materials storeroom and into the production area. Direct materials issued to production are direct materialsused. To determine materials used, begin with materials purchases, add beginning materials inventory, and subtract ending materials inventory. Supplies like nails, glue, lubricants, and paints are usually not worth the effort of tracking as direct materials, so most companies refer to these items as indirect materials, and these are included as part of factory overhead costs. At McDonald’s, potatoes used

- 31. to make French fries are direct materials, while the salt added to the fries is an indirect material. Directlaborcosts are wages paid to workers who directly process the product. In Figure 1.7, assembly line workers would be direct labor. At McDonald’s, the wages paid to the cooks are direct labor costs. Factory overhead costs include all manufacturing costs that are not materials or direct labor. Manufacturing overhead, factory burden, and indirect manufacturing costs are other names for these costs. Obviously, a wide variety of costs fall into this category, such as maintenance staff wages, factory managers’ salaries, factory utilities costs, and factory equipment depreciation and repair costs. Hundreds of different cost accounts could be grouped under manufacturing overhead. Certain workers’ tasks could be overhead in one company and direct labor in another. For example, materials handlers and quality control personnel costs could be accounted for as either direct or indirect labor. Generally, if the worker has direct contact with the product or the production process, the cost is direct labor. Generally, support tasks are indirect labor—part of overhead. At McDonald’s, a particular restaurant manager’s salary is an indirect labor cost. Historically, the three cost groups were assumed to be about equal portions of total product cost. Today, automation reduces direct labor and causes factory overhead to increase. As more production is generated from the same capacity, materials as a percentage of total cost may also increase. Thus, managers have paid more attention to direct materials and overhead costs because they have grown as a portion of total

- 32. manufacturing costs. TypesofProductCosts Direct materials and direct labor costs are often viewed as direct product costs since they are easily identi�ied with speci�ic products and units of product. Factory overhead is usually thought of as indirect productcosts. Factory overhead is not easily traced to speci�ic products or units. For example, the plant manager’s salary cannot be tied to speci�ic product units in a multiproduct factory, since the manager is responsible for all activities in the factory. An exception may exist for a few overhead costs that may be traced to speci�ic products and be considered direct costs. Figure 1.8 illustrates these concepts and shows a dotted line between factory overhead and direct costs to indicate this possibility. At McDonald’s, the cost of hamburger buns is a direct product cost, while the restaurant’s electricity costs are indirect product costs. 7/30/2019 Print https://content.ashford.edu/print/Schneider.4937.17.1?sections= navpoint-1,navpoint-7,navpoint-8,navpoint-9,navpoint- 10,navpoint-11,navpoint-12,n… 19/93 Figure1.8:Productcostsandproductcostgroups Direct materials and direct labor are also known as the primecosts of a product. These costs are easily traceable to a speci�ic product. Direct labor and factory overhead are called conversion costs. In the factory, materials are “converted” into �inished product using

- 33. labor and all of the factory’s supporting resources—overhead costs. ContemporaryPractice1.1:SurveyonIndirectCosts In a survey of 185 European companies in various industries, respondents ranked the importance of indirect cost categories (other than personnel costs) as follows: Ranking CostCategory 1 Information Technology 2 Energy 3 Maintenance 4 Fleet Management 5 Marketing 6 Facility Management 7 Freight 8 Logistics 9 Telecommunications 10 Insurance 11 Travel Expenses 12 Tools/Supplies

- 34. Source:Wald,A.,Schneider,C.,Schulze,M.&Mar�leet,F.(2013,No vember/December).Astudyonthestatusquo,currenttrends,and successfactorsincostmanagement.Cost Management,28–38. 7/30/2019 Print https://content.ashford.edu/print/Schneider.4937.17.1?sections= navpoint-1,navpoint-7,navpoint-8,navpoint-9,navpoint- 10,navpoint-11,navpoint-12,n… 20/93 CalculatingUnitCosts Productcosting assigns costs to units of product. The approach is to divide the number of units produced into total manufacturing costs to obtain a cost per unit of product. For example, a highly automated factory produces a variety of tablet computers. The same production processes are used for all models with minimal costs to change over the production line. Three million tablet computers are manufactured every month. Different circuit boards distinguish the models. March production data by product line are as follows: Deluxe SuperDeluxe Basic Total Direct materials costs $3,600,000 $4,200,000 $1,500,000 $9,300,000 Indirect other costs 6,000,000 Total costs $15,300,000 Units produced 120,000 120,000 60,000 300,000

- 35. Direct materials costs per unit $30.00 $35.00 $25.00 $31.00 Indirect other costs per unit 20.00 20.00 20.00 20.00 Product cost per unit $50.00 $55.00 $45.00 $51.00 Note: The “Indirect other costs per unit” of $20.00 is obtained from dividing $6,000,000 of “Indirect other costs” by the 300,000 units produced. The costing approach is to divide the total costs of $15,300,000 by 300,000 tablet computers. However, the $51.00 average cost hides the different direct costs of each model of circuit board. A second approach identi�ies materials costs as direct to each model and averages all other costs over all units. This produces a high cost of $55.00 for Super Deluxe models and a low cost of $45.00 for Basic models. More complex costing is needed if different models use different amounts of resources. The goal is to obtain the most accurate unit cost, given managers’ decision-making needs. 7/30/2019 Print https://content.ashford.edu/print/Schneider.4937.17.1?sections= navpoint-1,navpoint-7,navpoint-8,navpoint-9,navpoint- 10,navpoint-11,navpoint-12,n… 21/93 1.5CostBehavior To say that a cost “behaves” in a certain way is somewhat misleading. Costs result from taking actions or from the mere passage of time. Something drives a cost—some activity, decision, or event. Selling one

- 36. more hamburger involves a burger, a bun, a container, a napkin, and any condiments used. But selling one more hamburger has no impact on supervision, equipment rental, or advertising costs. Building lease expense will not change unless the lease includes a rental payment based on a percentage of sales. Cost behavior, then, is the impact that a cost driver has on a cost. Which costs can be expected to remain constant when the amount of work activity increases or decreases? Also, which costs increase as more work is performed? If costs are to be estimated and controlled, we need to know whether or not costs will change if conditions change, and, if so, by what amount. Cost behavior is often viewed as a dichotomous pattern—either variable or �ixed. But in the real world, many behavior patterns exist since most costs are not strictly variable or �ixed. Thus, the concepts of semivariable and semi�ixed costs add complexity to cost behavior studies. It may oversimplify the analysis, but a split between variable and �ixed is common and is used frequently. VariableCosts A variable cost changes in total in direct proportion to changes in business activity such as units produced or hours worked. A decrease in activity brings a proportional decrease in total variable cost, and vice versa. For example, direct materials costs are usually variable costs since each unit produced requires the same amount of materials. Thus, materials costs change in direct proportion to the number of units manufactured. At McDonald’s, the cost of raw hamburger meat is a variable cost.

- 37. A proportional relationship between activity and cost has these important characteristics: Variable cost is a rate per unit of activity or output. A variable cost per unit remains constant across a reasonable range of activity. The slope of the total variable cost curve is the variable cost per unit—the added cost divided by the added units. For example, if a product costs $4.00 per unit, the expression $4X yields the total variable cost at X level. Figure 1.9 shows the behavior of variable costs on a per unit basis and in total, and also highlights the variable cost line’s slope. Figure1.9:Behaviorofvariablecosts 7/30/2019 Print https://content.ashford.edu/print/Schneider.4937.17.1?sections= navpoint-1,navpoint-7,navpoint-8,navpoint-9,navpoint- 10,navpoint-11,navpoint-12,n… 22/93 FixedCosts A �ixedcost is constant in total amount regardless of changes in business activity level. Costs such as the plant manager’s salary, depreciation, insurance, and rent usually remain the same in total regardless of whether the plant is above or below its expected level of operations. At McDonald’s, the cost of heating the restaurant is a �ixed cost since the cost does not change with activity such as labor hours or amount of food prepared.

- 38. Important characteristics of a �ixed cost are: Fixed cost is a lump of costs that is not normally divisible and does not change as activity or volume changes. A �ixed cost remains constant across a reasonable range of activity. The �ixed cost per unit decreases as activity or volume increases and increases as activity or volume decreases. For example, March’s rent is stated as a dollar amount for that month, not as an amount per unit of output or even per hour of use. By de�inition, total �ixed costs are constant, causing the �ixed cost per unit to vary at different levels of activity. Figure 1.10 shows the behavior of �ixed costs on a per unit basis and in total. When a company produces a greater number of units, the �ixed cost per unit decreases. Conversely, when fewer units are produced, the �ixed cost per unit increases. This variability of �ixed costs per unit creates problems in product costing. The cost per unit depends on the number of units produced or on level of activity. Figure1.10:Behaviorof�ixedcosts 7/30/2019 Print https://content.ashford.edu/print/Schneider.4937.17.1?sections= navpoint-1,navpoint-7,navpoint-8,navpoint-9,navpoint- 10,navpoint-11,navpoint-12,n… 23/93

- 39. Certain �ixed costs can be changed by management action. These are discretionary �ixed costs. Discretionary �ixed costs are expenditures that managers can elect to spend or not to spend. For example, a company might budget the cost of consultants at $20,000 per month for the coming year. But the contract states that the company can cancel the contract at any time. Management maintains discretionary control over the spending. On the other hand, if the contract guarantees the consultant a 12- month relationship and the contract has been signed, a committed �ixed cost has been created. A committed�ixedcost is one over which a manager has no control and must incur. Advertising cost for McDonald’s is a discretionary �ixed cost. Depreciation on McDonald’s restaurant equipment is a committed �ixed cost. An interesting observation is necessary here. Managers can, with time and intent, change the cost behavior of certain activities. For example, variable direct labor costs can be replaced by a �ixed cost by guaranteeing full-time employment for some period, such as a three-year union contract. Or equipment could be leased on a short-term basis (day-to-day or even hourly) instead of purchased—replacing a �ixed cost with a variable cost. Also, automated equipment with a �ixed rent or depreciation could replace variable-cost manual labor. Thus, we recognize that managers can act to change certain cost behavior, particularly over time. ContemporaryPractice1.2:FixedVersusVariableExpenses “You can get quality people to invent, develop and design products for you on a percentage of the

- 40. products’ billing—in other words, on a variable expense basis. Many will want to work on upfront fees only, a �ixed expense. Salesmanship on your part can get them to charge your way. If they’re sold on your company, you personally, or the product, they’re more likely to comply with your wishes. Sometimes a compromise is required where you pay a modest upfront fee and a modest percentage on sales of the product.” Source:Reiss,B.(2010,November3).Outsourcingturns�ixedcostsi ntovariablecosts.Entrepreneur.Retrievedfrom http://www.entrepreneur.com/article/217487(http://www.entrepr eneur.com/article/217487) http://www.entrepreneur.com/article/217487 7/30/2019 Print https://content.ashford.edu/print/Schneider.4937.17.1?sections= navpoint-1,navpoint-7,navpoint-8,navpoint-9,navpoint- 10,navpoint-11,navpoint-12,n… 24/93 ExpressingVariableandFixedCosts—ACostFunction Since a variable cost is a rate, it is a function of an independent variable—an activity or output level. Unit variable costs can be converted into total variable costs only by knowing the activity or output level. Fixed costs are �irst expressed as a total, lump sum amount, a constant. Total �ixed costs can be converted into a rate per unit only if the activity or output level is known. In the following example, the cost per unit of $7 and total costs of $700,000 can be found only if the output of 100,000 units is known.

- 41. Costsof100,000Units Costsof120,000Units CostperUnit TotalCosts CostperUnit TotalCosts Variable costs $4.00 ⟶$400,000 $4.00 ⟶$480,000 Fixed costs 3.00 ⟵300,000 2.50 ⟵300,000 Total $7.00 $700,000 $6.50 $780,000 If the production level increases to 120,000, both the cost per unit and total costs change. A decrease in the cost per unit from $7 to $6.50 results from spreading �ixed costs of $300,000 over more units— 120,000 instead of 100,000. The increase in total cost equals the variable costs for the additional 20,000 units. A decrease in volume has similar reverse impacts—the cost per unit increases, but total costs decline. Three factors must generally be known to perform cost analyses: 1. The variable cost rate 2. The �ixed cost amount 3. The level of activity or output Notice that if we know the bold numbers in the example above and the activity level, we can calculate all other numbers. These factors can be brought together in a cost function—an expression that mathematically links costs, their behavior, and their cost driver. In the example, the expression is: Total costs = $300,000 + $4(X), where X is the number of units

- 42. produced. This cost function can be symbolically shown as: Total costs = a + b(X), where a is total �ixed costs and b is variable cost per unit. This is an important formula in managerial accounting. Understanding these relationships can give insight into cost behavior for planning, control, and decision making. By knowing the activity level and cost function, we can calculate either total costs or costs per unit. DeterminingtheCostFunctionUsingTotalCostsandActivityLevels In this example, let’s assume we know the total costs ($700,000 and $780,000) at both activity levels (100,000 and 120,000 units). How do we obtain the cost function? First, we calculate the variable cost per unit as follows: 7/30/2019 Print https://content.ashford.edu/print/Schneider.4937.17.1?sections= navpoint-1,navpoint-7,navpoint-8,navpoint-9,navpoint- 10,navpoint-11,navpoint-12,n… 25/93 The $4 per unit amount is the variable cost per unit in the cost function. The change in cost from a change in activity yields the slope of the total variable cost line. To obtain the �ixed cost, which is a in the cost function, we take the total costs at either activity level and subtract the total variable costs at that level, as follows:

- 43. $780,000 – ($4 × 120,000 units) = $300,000 or $700,000 – ($4 × 100,000 units) = $300,000 We now have both a and b. Total cost = $300,000 + $4 (X). ObtainingtheCostFunctionUsingPerUnitCostsandActivityLevels Using the same example, per unit costs were $7 at the 100,000 units activity level and $6.50 at 120,000 units. First, we calculate total costs at each level by multiplying the cost per unit by the activity level as follows: $7 per unit × 100,000 = $700,000 and $6.50 per unit × 120,000 = $780,000 Second, we follow the same procedure as shown previously in converting total costs into the cost function. The same calculations could be applied separately to total variable costs for b and to total �ixed costs for a. Calculations at both levels produce the same cost function. One danger in converting total �ixed costs into cost per unit is that the unit cost can be misinterpreted. It might be assumed that $7 is the variable cost—forgetting that the $300,000 is a �ixed cost. At different activity levels, the per unit cost will be different. Even in solving homework problems, students are in danger of missing the impact of volume changes on total costs and unit costs if only costs per unit or total costs are used. RelevantRange

- 44. In Figures 1.9 and 1.10, activity is assumed to start at zero and increase to very high levels. Realistically, the cost function holds only for a much narrower range of activity—a relevant range. A relevantrange is the normal range of expected activity. Management does not expect activity to exceed a certain upper bound nor to fall below a lower bound. Production activity is expected to be within this range, and costs are budgeted for these levels. In cost analysis, costs are expected to behave as de�ined within the relevant range. The cost function is assumed to be valid for this range of activity. Usually, past experience establishes the relevant range. Total �ixed costs are �ixed and total variable costs are variable within the relevant range. In the above example, the volume range was between 100,000 and 120,000 units. The cost function of $300,000 plus $4 per unit is valid between 100,000 and 120,000 units as shown in Figure 1.11. If planned production were 130,000 units, our cost function might not be valid or useful. Figure1.11:Costpatternsusingarelevantrange 7/30/2019 Print https://content.ashford.edu/print/Schneider.4937.17.1?sections= navpoint-1,navpoint-7,navpoint-8,navpoint-9,navpoint- 10,navpoint-11,navpoint-12,n… 26/93 SemivariableandSemi�ixedCosts Figure 1.12 illustrates cost functions that are neither strictly

- 45. variable nor �ixed. In the real world, very few costs are truly variable or �ixed. Semivariablecosts change but not in direct proportion to the changes in output. Some semivariable costs, called mixed costs, may be broken down into �ixed and variable components, thus making it easier to budget and control costs. Using the cost function techniques shown previously, �ixed and variable parts can be identi�ied. In Example A of Figure 1.12, telephone expenses may include a monthly basic connection fee (�ixed) plus a per- minute charge for each call (variable). Semi�ixedcosts or step-�ixedcosts are typi�ied by step increases in costs with changes in activity as shown in Example B. Activity can be increased somewhat without a cost increase. However, at some activity level, additional �ixed cost must be incurred to expand capacity. An example is adding an additional full-time worker when sales increase beyond a certain level. If many narrow steps exist, a step- cost pattern may approximate a variable cost. Or with wide steps, one step may encompass the entire relevant range and the step cost appears as a �ixed cost. Figure1.12:Examplesofsemivariableandsemi�ixedcost patterns Example C shows a cost that increases but at a lower cost per unit as activity increases. An example is increased worker ef�iciency as activity increases, resulting in a lower per unit cost. This is a nonlinear cost. Example D shows a piece-wiselinearcost. It is a constant variable rate until a certain activity level is reached, then the variable cost per unit increases. Perhaps an electric utility offers a low per kilowatt rate for the �irst 500 kilowatts and a higher rate beyond that

- 46. level. 7/30/2019 Print https://content.ashford.edu/print/Schneider.4937.17.1?sections= navpoint-1,navpoint-7,navpoint-8,navpoint-9,navpoint- 10,navpoint-11,navpoint-12,n… 27/93 1.6CostConceptsforPlanningandControlling This section introduces terminology relating to traceability and controllability of costs. These concepts are useful for planning and control purposes. DirectCostsVersusIndirectCosts Costs are often de�ined as being direct or indirect with respect to a cost object—an activity, a department, or a product. If a cost can be speci�ically identi�ied with a particular cost object, it is traced to the cost object and is considered to be a direct cost. A direct cost is also called a traceable cost. The cost of installing a sunroof on a particular car is a direct cost of that car because it is traceable to that particular car. If no clear link between a cost and the cost object is apparent, the cost is an indirectcost (also called a commoncost). For example, the heating cost for a physical therapy center is an indirect cost to each patient being served there. The same cost can be direct for one purpose and indirect for another. For example, the salary of the St. Louis of�ice manager is a direct cost of that branch. But within the branch of�ice where numerous products are sold, the manager’s salary is an indirect cost of speci�ic

- 47. products. At McDonald’s, cleaning supplies are a direct cost for a particular restaurant, but corporate legal expenses are an indirect cost for a particular restaurant. Indirect costs not traceable to particular products or departments may need to be allocated to those cost objects. A cost object may use a resource, but the amount used may not be easily measured. For example, a shoe department occupies 2,000 square feet of a 50,000 square foot store and accounts for 10% of sales and 6% of pro�its. If the rent for the entire store is $300,000 per year, how much should be allocated to the shoe department—$12,000 (space), $18,000 (pro�its), $30,000 (sales), or some other amount? No cost allocation is absolutely correct, and different viewpoints will argue for different allocations. The allocation process should attempt to link the cost, the use of the resource, and the activity or output. ControllableCostsVersusNoncontrollableCosts Another important aspect of cost is the distinction between costs that can and cannot be controlled by a given manager. This cost classi�ication, like the direct and indirect cost classi�ication, depends on a point of reference. If a manager is responsible for a cost, that cost is a controllable cost with respect to that manager. If that manager is not responsible for incurring a cost, it is a noncontrollablecost with respect to that manager. The entire cost control system rests on who can control each cost. All costs are controllable at some level of management. Every cost in an organization is controllable by some manager in that organization. Costs should be planned or

- 48. budgeted by the manager who has responsibility for that cost. For a McDonald’s restaurant manager, the cost of utilities usage is controllable, while property insurance costs are noncontrollable. 7/30/2019 Print https://content.ashford.edu/print/Schneider.4937.17.1?sections= navpoint-1,navpoint-7,navpoint-8,navpoint-9,navpoint- 10,navpoint-11,navpoint-12,n… 28/93 1.7ContributionMarginandItsManyVariations Thus far, we have de�ined cost terms. But managerial responsibility for pro�it measurement is even more important. Revenue is added to the analysis. While net pro�it evaluates the entire �irm, determining pro�itability of parts of a �irm requires more precise pro�it measures. The term we use is contribution margin, which is the revenue minus certain costs, a margin. This margin contributes to covering all remaining costs and to earning a net pro�it. Figure 1.13 shows �ive variations used in different situations. Figure1.13:Variationsofcontributionmargin VariableContributionMargin—PerUnit,Ratio,andTotalDollars The basic and most common de�inition of contribution margin is sales minus variable costs. Variable contributionmargin is a more explicit term because only variable items (revenue and costs) are included in the calculation. This contribution margin contributes towards covering �ixed costs and provides for a net pro�it.

- 49. As an example, a salesperson is selling a product for $20 per unit. The �irm buys the item for $12 per unit and pays the salesperson a 10% commission on sales. The �irm expects to sell 10,000 units. Variable contribution margin can be shown as follows: VariableContributionMargin PerUnit Ratio TotalDollars Sales (10,000 units) $20 100% $200,000 Variable costs: Costs of sales and commissions ($12 plus 10% of $20) 14 70 140,000 Variable contribution margin $6 30% $60,000 Thus, the contribution margin can be expressed as either $6 per unit, 30% of sales, or $60,000. Depending on the analysis needed, we may use one, two, or all three versions. From total variable contribution margin, we subtract �ixed expenses—the remaining expenses— to arrive at net pro�it. ControllableandDirectContributionMargins 7/30/2019 Print https://content.ashford.edu/print/Schneider.4937.17.1?sections= navpoint-1,navpoint-7,navpoint-8,navpoint-9,navpoint- 10,navpoint-11,navpoint-12,n… 29/93

- 50. The next contribution margin concept looks at managerial control and is used when a manager has revenue and cost responsibility. Costs controllable by the manager are typically variable costs and controllable �ixed costs. These costs are subtracted from sales to yield controllablecontributionmargin or controllable margin. This represents the amount available to cover any noncontrollable expenses and includes any company net pro�it. Note that the de�initions of controllable and noncontrollable developed previously are used for both revenue and costs. Controllable contribution margin is used to evaluate managerial performance. However, this is not the net pro�it that the manager generates for the company, since noncontrollable costs must be covered before any net pro�it is earned. Direct or segmentcontributionmargin or segment margin is a segment’s revenue minus its direct costs. A segment might be a product, a region, or a division. De�initions of direct and indirect were discussed earlier and focus on traceability. As an example, the direct contribution margin of a product line is sales less product-line cost of sales, product-line advertising costs, and any other costs traceable to that product line. The product line’s direct contribution margin is the amount remaining to cover company common costs and to earn company pro�its. IllustrationofAllContributionMarginConcepts Pearl Engel owns three Burgers Plus locations. Figure 1.14 presents a summary income statement, expanded for the Grand Avenue location. Variable contribution margin is shown in total dollars for each

- 51. store and also as a ratio for the Grand Avenue store. Directcontrollable�ixedexpenses include assistant managers’ salaries, maintenance services, and other �ixed costs that the store manager controls. The controllable contribution margin is the pro�it on which the Grand Avenue manager will be evaluated and rewarded (a bonus for meeting pro�it goals or pro�it improvement). Direct noncontrollable �ixed expenses include rent on the building and the outlet manager’s salary, which are probably controlled by Engel. Figure1.14:Contributionmarginanalysisbystore This direct or store contribution margin is used to measure the pro�it performance of each store. Measuring store pro�itability stops at the direct contribution margin. Direct contribution margin is the 7/30/2019 Print https://content.ashford.edu/print/Schneider.4937.17.1?sections= navpoint-1,navpoint-7,navpoint-8,navpoint-9,navpoint- 10,navpoint-11,navpoint-12,n… 30/93 �inest-tuned pro�it measure that is free of allocations. Common corporate expenses, which include Engel’s salary and other corporate expenses, cannot be traced to the three locations. Contribution margin per unit requires more detail. Engel has set target contribution margins for her three main burger products as follows:

- 52. Averagefor CheapBurger DoubleBurger TripleBurger Selling price per unit $1.00 $2.00 $3.00 Variable product costs per unit 0.65 1.20 1.50 Variable contribution margin per unit $0.35 $0.80 $1.50 Variable contribution margin ratio 35% 40% 50% Note that the other variable expenses (probably supplies and condiments) in Figure 1.14 cannot be traced accurately to each product. As shown in Figure 1.14, actual burger margins can be compared across all stores and to margin targets. Ms. Engel has numerous versions of pro�itability for each location. She will use each to answer speci�ic questions about her products, managers, and stores. Common use of the term contribution margin frequently means variable contribution margin. To avoid misunderstanding, de�ine which contribution margin you are using. 7/30/2019 Print https://content.ashford.edu/print/Schneider.4937.17.1?sections= navpoint-1,navpoint-7,navpoint-8,navpoint-9,navpoint- 10,navpoint-11,navpoint-12,n… 31/93 Summary & Resources

- 53. ChapterSummary Accounting information is provided from a system that handles the requirements of two branches of accounting: �inancial accounting and managerial accounting. Financial accounting presents accounting information to parties outside the organization. Managerial accounting organizes accounting information for internal management. Internal reporting is generally directed to the decision areas mentioned earlier. The ethical conduct and integrity of the management accountant are critical to the success of the accountant’s mission. Ethical situations are common and often complex. Management accountants have a special responsibility to their management colleagues and to themselves to uphold high ethical standards. Cost analysis and income measurement are equally important to service, merchandising, or manufacturing �irms. Tracing cost �lows is important to understanding the conversion of materials, direct labor, and overhead into a product or service. The cost driver is the link between resources used and outputs. Different decisions need different costs. A “cost” must have an adjective attached to give it meaning. In general, costs have many attributes, but the three most important ones for using cost concepts are cost behavior, traceability, and controllability. Variable and �ixed costs behave differently when activity levels change. Variable costs are naturally expressed as a rate; �ixed costs are naturally a lump of costs. Fixed and variable costs can be expressed as a cost function, such as a + b (X), where a is the �ixed cost, b is the variable rate, and X is the level of activity.

- 54. Direct costs are traceable; indirect costs are nontraceable. Controllability refers to a speci�ic manager’s authority to incur the cost and responsibility to use the resource generating the cost. Contribution margin is revenue minus a subset of costs. Variable contribution margin can be expressed as an amount per unit, a ratio, or total dollars. Controllable contribution margin is used to evaluate the manager, and direct or segment contribution margin is used to evaluate the segment. KeyTerms billofmaterials A complete list of all materials used in a product. Certi�iedManagementAccountant(CMA) A person who has passed a qualifying examination sponsored by the Institute of Management Accountants, has met an experience requirement, and participates in continuing education. committed�ixedcost A �ixed cost over which a manager has no control and must incur. commoncost A cost that has no clear link to a speci�ic cost object. contributionmargin Sales revenue less variable costs.

- 55. 7/30/2019 Print https://content.ashford.edu/print/Schneider.4937.17.1?sections= navpoint-1,navpoint-7,navpoint-8,navpoint-9,navpoint- 10,navpoint-11,navpoint-12,n… 32/93 controllablecontributionmargin Variable contribution margin less direct controllable �ixed expenses (represents the amount available to cover any noncontrollable expenses and includes any company net pro�it). controllablecost A cost that a manager has the ability to in�luence. controller The person responsible for managing the entire accounting function. conversioncosts Direct labor plus manufacturing overhead (costs incurred to convert raw materials into �inished products). cost The amount of resource given up to gain a speci�ic objective or object. costbehavior How a cost changes with changes in business activity. costdrivers Measures that link activities that create outputs to resources that are used. costfunction

- 56. An expression that mathematically links costs, their behavior, and their cost driver. costobject Any purpose for accumulating costs. costofgoodsmanufactured Total cost of goods completed during the period. costofgoodssold The total of direct materials, direct labor, and manufacturing overhead costs associated with the goods that have been sold during the period. directcontributionmargin Controllable contribution margin less direct noncontrollable �ixed expenses (re�lects the amount remaining to cover common costs and earn pro�its). directcontrollable�ixedexpenses Fixed expenses that are traceable and that a manager has the ability to in�luence. directcost A cost that is traceable to a cost object. directlaborcosts Wages paid to workers who work directly on the product. directmaterialscosts Costs of the physical components of the product. 7/30/2019 Print

- 57. https://content.ashford.edu/print/Schneider.4937.17.1?sections= navpoint-1,navpoint-7,navpoint-8,navpoint-9,navpoint- 10,navpoint-11,navpoint-12,n… 33/93 directmaterialsused Materials issued to production. directnoncontrollable�ixedexpenses Fixed expenses that are traceable, but that a manager is not able to in�luence. directproductcosts Costs that can be traced to speci�ic products. discretionary�ixedcosts Expenditures that managers can elect to spend or not to spend. factoryoverheadcosts All manufacturing costs that are not direct materials or direct labor. �inancialaccounting The branch of accounting that organizes accounting information for presentation to interested parties outside of the organization. �inishedgoodsinventory Products that have been completed and are ready for sale. �ixedcost A cost that remains constant, regardless of changes in a company’s activity. indirectcost A cost that has no clear link to a speci�ic cost object.

- 58. indirectproductcosts Manufacturing costs that cannot be traced to a speci�ic product. managementaccountant An accountant who prepares information for a company’s decision makers. managerialaccounting The branch of accounting that meets managers’ information needs. materialsinventory Materials that are stored by the company. mixedcost A cost that contains both variable and �ixed elements. noncontrollablecost A cost that a manager is not able to in�luence. nonlinearcosts A cost for which the cost function cannot be represented as a straight line. periodcosts Operating costs that are expensed in the period in which they are incurred. 7/30/2019 Print https://content.ashford.edu/print/Schneider.4937.17.1?sections= navpoint-1,navpoint-7,navpoint-8,navpoint-9,navpoint- 10,navpoint-11,navpoint-12,n… 34/93

- 59. piece-wiselinearcost A cost function consisting of connected straight lines with differing slopes. primecosts Direct materials cost plus direct labor cost. productcosting The process of attaching costs to units of product. productcosts Costs that are treated as assets until the products are sold. relevantrange Normal range of expected activity. segmentcontributionmargin A segment’s revenues minus its direct costs. semi�ixedcosts Costs that are typi�ied by step increases in costs with changes in activity. semivariablecost A cost composed of a mixture of �ixed and variable components. step-�ixedcosts Costs that are typi�ied by step increases in costs with changes in activity. totalmanufacturingcosts The sum of direct materials, direct labor, and factory overhead costs.

- 60. traceablecost A cost that can be directly linked to a cost object. variablecontributionmargin Sales revenues less all variable expenses. variablecost A cost that changes in proportion to a change in a company’s activity. workinprocessinventory The cost of products that have been started in the manufacturing process but have not yet been completed. ProblemforReview Rabin Corporation operates sales, administrative, and printing activities from a facility in Augusta. It prints, prepares, and mails a wide variety of promotional materials. The following selected costs relate to the �irm’s activities and particularly to the factory’s Mail Preparation Department. a. Production paper used in Mail Preparation Department b. Hourly wages of production personnel in Mail Preparation Department 7/30/2019 Print https://content.ashford.edu/print/Schneider.4937.17.1?sections= navpoint-1,navpoint-7,navpoint-8,navpoint-9,navpoint- 10,navpoint-11,navpoint-12,n… 35/93 c. Factory property taxes and insurance

- 61. d. Supplies used, which changes with printing volume in Mail Preparation Department e. Contract signed by Mail Preparation Department manager for an annual maintenance fee on postage application machinery f. Equipment depreciation in Mail Preparation Department g. Building depreciation h. Sales commissions i. Advertising agency contract costs for a special program j. Annual computer staff; uses the same number of staff all year—half for operations, which includes the Mail Preparation Department, and half for administrative work Questions: Based on reasonable assumptions about Rabin Corporation, classify each cost as: 1. Variable or �ixed cost 2. Controllable or noncontrollable by the supervisor of the Mail Preparation Department 3. Direct or indirect product costs or period costs Solution : CostBehavior

- 62. UnderControlof DepartmentManager ProductCost Cost Item Variable Cost Fixed Cost Yes No Direct Cost Indirect Cost Period Cost (a) X X X (b) X X X