Hiroshige's Mini-Fujis: Climbable Replicas of Mount Fuji in Edo Period Japan

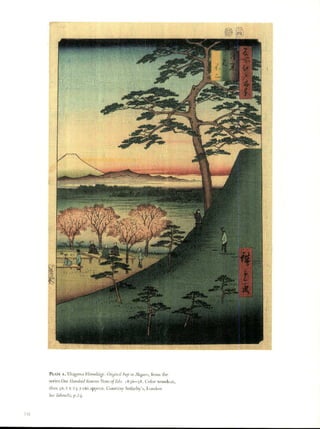

- 1. PLXfE i. LItagawa Hiroshige. Ori,inalFuji in Aleguro, from the series One Hundred FRnaous Viens oJ'Edo 856-58. Color woodcut, 18 6hban, 36.2 X 23.7 cm approx. Courtesy Sotheby's, London 2 See Takeuchi, p. 4.

- 2. PLATE 2. Utagawa Hiroshige. Neir Fnji infMegaro, from the series One Hundred Famons Vhuies oJ'Fdo. 1856,-58. Color woodcut, iban. 36.2 X 23.7 cm approx. CourtCsV Sotheby's, London See Takeuchi, p. 2 4. IM PR S S 0 N S i

- 3. PLATE 3. Katsushika Hokusai. Group Climbing] the .Mountain, from the series Thirty-Six Vie••s of Mount Fuji. Early 183 ON. Color woodcut, jSban. Courtesy Sothebv's, London See Takeuchi, p 36.

- 4. PLATE 4. Hashimoto Sadahide ( 1807- 1873). Pilqrimns in the I VOnib Caiv on Mount Fuji. 18 57. Color woodcut triptych, Oban- 3 5.4 x 24.4 Cut approx. each. D. Max Mocriman Collection. Photo: John Deane See Takeuchi, p 37 I M P R E S S 1 0IO S 2 1 N

- 5. 14

- 6. 1* < PLATE 5. Utagawa Hiroshige. "Mountain Opening" at PLATE 6. Utagawa Hiroshige. Manpachi Restaurant:Evening View of Fukagawa Hachiman Shrine, from the series One Hundred Yanagibashi (Ynagibashiyakei, Manpachi), fiom the series Collection of Famous liews o?fEdo. 1856-58. Color woodcut, 5ban. FTmors Edo Restaurants (Edo konei kaitei zukushi). 18 38-40. Color 36.2 X 23.7 cm approx. Courtesy Sotheby's, London woodcut, 6ban. 2 2.1 x 35-5 cm. Spencer Museum of Art, Lawrence, See Takeuchi, p. 44. Kans., Gift of H. Lee Turner. Photo: Robert Hickerson See Thonsen, p. 48. IM P R E S S I 0 N S 24 15

- 7. I i 1 y4 . 4'Th H

- 8. PLATE 9. Utagawa Hiroshige. Uekiya Restaurant:SnoW Viewing at J)okuboji Temple (Mokuboy Yukimi, Uekiva), firom the series Collection of Famous Edo Restaurants (Edo k6mei kaitei zukushi). 1838-40. Color woodcut, oban. 22.9 x 35.2 cm. Elvehjem Museum of Art, University of Wisconsin- Madison, Bequest of John H. Van Vleck, 198 0.1474 See Thomsen, p. 54. < PLATE 7- Utagawa Hiroshige. Tagaivaya Restaurant: In Front of Daionji Temple (Daionji mae, Tagavaqya), from the series Collection of Famous Edo Restaurants (Edo k5mei kaitei zukushi). 1838-40. Color woodcut, 5ban. 22.5 X 35 tM. Spencer Museum of Art, Laxrence, Kans., Gift of H. Lee TIurner. Photo: Rohert Hickerson See Thomsen, p. 52. < PLATE 8. Utagawa Fliroshige. lusashiva Restaurant: Ushijima (Ushijima, Musashiya), friom the series Collection of •amous Edo Restaurants (Edo kt7mei kaitei zukushi). 1838 -40. Color woodcut, 51'an. 26. 1 x 37.7 cm. Hiraki Ukiyo-e Museum, Tokyo See TAomsen, p. 53. I NI P R E S I (O N S 2 1

- 9. PLATE i i. Utagawa Hiroshige. Aoyagi Restaurant:Ry6goku Diistrict > (Ryoqoku, Aoyagi), from the series Collection of Famous Edo Restourants (Edo komei kaitei zukushi). 1838-40. Color wAoodcut, 5ban. 23 x 35. 5 cm. Spencer Museum of Art, Lawrence, Kans., Gilt of H. Lee Turner. Photo: Robert Hickerson See Thomsen, p. 55. PLATE io. Utagawa Hiroshige. Mokuboji Temple, from Picture PLATE 12. Utagawa Hiroshige. Shokintei Restaurant: )Jushima Tenjin > Book of Edo Souvenirs (Ehon Edo miyage), vol. 1 8 5o. Color Shrine (Yushona Tenjin, Shokintei), from the series Collection oJ famous woodblock-printed book. I8.r X 14.6 cm. Former collection Edo Restaurants (Edo k6mei kaitei zukushi). 1838 -40. Color woodcut, of Arthur Wesley Dow. C. V Starr East Asian Library, oban. 23 x 3 5.5 cm. Spencer Museum of Art, Lawrence, Kans., Columbia University; New York City Gift of H. Lee Turner. Photo: Robert Hickerson See Thomsen, p. 54. See Thomsen, p. 67. 18

- 10. IMPRESSIO NS 24 19

- 11. PLATE 13. Toyohara Kunichika. Eight Views of'Edo: Clear Breezes at Ry53goku Bridge (Edo hakkei no uchi: Ry5goku no seiran) c. 1867. Color woodcut, iiban triptych. 34.7 X 23.5 cm approx. each. Spencer Museum of Art, Lawrence, Kans., Gift of Dr. and Mrs. George Colom. Photo: Robert Hickerson See Thomsen, pp. 6o-6i. (30

- 12. IM 11 R E S S I1 N S 2 121

- 13. PLATE 14. Okumura Masanobu. Burning Maple Leaves to Heat Sake. c. 17 750. Color woodcut, large oban, benizuri-e. 41.6 X 29.9 cm. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Harris Brisbane Dick Fund and Rogers Fund, 1949 (JP 3079). Photo: © 1994 The Metropolitan Museum of Art See Thompson, P. 72.

- 14. PLATE 15. Suzuki Harunobu or pupil. Hakt Rakuten. c. i77o. Color woodcut, chuban. 27.8 X 20.9 cm. Honolulu Academy of Arts, Gift of James A. Michener, 1971 (21, 7344) See Thompson, p. 81. I M P R E S S I 0 N S 24 23

- 15. 4- Fig. i. Utagawa Hiroshige. Original liji in Megunro, from the series Fig. 2. Utagawa H iroshige. Nevv Fup in fepuro, One Hundred Fainous Qeivs ofEdo, 1856-58. Color woodcut, jb(n. from the series One Hundred Fainous Wews ot Edo. 36. 2 x 23.7 cm approx. Courte.s Sotheby's, London i856-58. Color woodcut, oban. 36.2 X 23.7 cmn This Mini-Fuji was constructed in 18 12, 17 years before the "New approx. Courtesy Socheby's, London Fuji" (pl. 2/fig. 2) located 5oo yards tarther north.

- 16. Making Mountains: Mini-Fujis, Edo Popular Religion and Hiroshige's One Hundred Famous Views of Edo ME/LINDA TAKEUCHI T IHREL 01 THL WOODCIITS from the series One Hundred Famous Q}eis Edo, produced by Utagawa Hiroshige ( 79 7- 18 58) from 18 56 to Of 58, show climbable replicas of Mount Fuji located in and S around the Eastern Capital of Edo (present-day Tokyo). Although it is dif- ficult to tell from Hiroshige's images, these simulacra were connected with a flourishing Edo-period ( 1615- 1867) cult centered on the ritual ascent of the sacred mountain. In two of the woodcuts the little fabricated Fujis mirror the "original" Mount Fuji in Suruga Province (hereafter called the Suruga Fuji), while wittily playing havoc with scale (pIS. 1, 2/figs. 1, 2). It may seem ironic to have to distinguish the "original" Fuji from the others, but in addition to the manmade replicas there are numbers of similar cone-shaped mountains scattered throughout Japan, formed by the same volcanic process that created the Suruga Fuji and nicknamed Fuji.' The Fuji mounds include the zigzag path to the "summit" in imitation of the switchback routes up the Suruga Fuji's slopes. The New Fuji in Meguro pictured in figure 2 displays one of the religious landmarks associated with the cult: the "Fiat Rock" (eboshi iwa) central to the hagiography of this new religious movement. Hiroshige's climbers appear to be in what might be called "recreation mode": tea stalls and benches refresh these urban pil- grims-men, women and children-who seem to have come more for an outing under the beautifil spring cherry trees than for the religious expe- rience of ascending the proxy of a sacred mountain. No one wears the white pilgrims' clothing normally donned by the supplicants who climbed Japan's holy mountains and besides, the season is wrong for the ritual as- cent. Furthermore, women and children were banned from the male- dominated space at the summit of the Suruga Fuji, whereas Hiroshige's images make clear that this proscription did not apply to the Mini-Fujis (to use Henry Smith's term). In all, over a hundred artificial Mount Fujis were built during the Edo pe- riod, mostly in Eastern Japan, beginning in the late eighteenth centuryv Fifty-six survive in one formn or another. Hiroshige's cool, distant vision affords little sense of the popular enthusiasm that these structures generated. How might we categorize these fabrications? Are they little artificial land- scapes? Do they belong to the realm of topographically mimetic gardens, like those at Suizenji in Kvushu or the Silver Pavilion in Kyoto, which in- clude conical forms intended to suggest Fuji? Are they visualizations of IM P R I S S I () N S 2

- 17. paradise, like the garden at the Phoenix Hall in Uji? Are they instruments of devotional praxis? Theme parks for an affluent leisure society.,? Cheap dilutions of a sacred site? Despite their elusive epistemological status, these heaps of dirt and stone projected a high profile-both cognitively and literally-in the Edo imaginary' To ignore them is to overlook one critical facet of the complex, discursive landscape of Japan. The Mini-Fujis illuminate aspects of the interaction of imagery; religion, nature and cul- ture. Politics, economics and gender are also part of this configuration. Perhaps the best way to understand the dynamics of these unusual struc- tures is to review some of the notions surrounding simulacra and minia- tures; to consider the Fuji cult itself and its reception in the Edo period; and then to speculate on why Hiroshioe coded his representations of this phenomenon as he did. SIMULACRA AND MINIATURES In the Western philosophical fabric, associating the simulacrum with cheap sentimentality, nostalgia and reductionism indicates a prominent strand of distrust of the replica. Plato's denunciation of the effigy as an instrument of deception (recall that he banished painters from his Republic) finds echoes in the charge of the French theorist Jean Baudrillard (b. 1929) that in simu- lation resides a false and infantile undermining of the real.' When in i9 19 Marcel Duchamp painted a mustache on a reproduction of the Mona Lisa, he offered glimmers of the problems that the technolo_ of replication was going to unleash upon world culture. As artists are often uncannily able to do, he raised the question of the collision between the aura attached to the "real" and the scent of legerdemain or chicanery that lingers about the "false." The need to differentiate between authentic and not authentic mav well be rooted in survival itself, biologically programmed into our species along with the fight-or- flight mechanism. It was once a life-or-death matter to be able to distinguish a real tiger from a shadow shaped like a tiger. Clones like Dolly the Sheep, quasi-humans like Darth Vader (part man, part ma- chine), technological marvels like Carol Doda (part flesh, part silicone), cyborgs, hydroponic vegetables and science fiction all work towards pushing the simul- acrum ever closer in our perception to some nightmarish twilight zone. In contrast, East Asian tradition, and Western too before (and after) the advent of scientific "logic," has employed the practices of symbolic substi- tution/replication to evoke and explicate the transcendent. Crystal and other precious objects substitute for physical relics of the Buddha in the way that wine and wafer are transubstantiated into the blood and body of Christ. The practice of equating real and fabricated mountains is verv ancient in Japan. The enormous man-made mounds (kqitin) in which rulers were entombed signiG' the magical potency associated with the replication of mountains. One finds sacred peaks duplicated in massive scale at the huge Buddhist stupas of Borobudur in Java and Bodhnath in Nepal, or reduced to the tabletop-sized forms of the magical Daoist hill-censer (poshaiihi), designed to emit the vapors of sacred mountains in the form of incense smoke. In the northeast of his capital the Song-dynasty emperor Huizong (i o8 2- 1 3 5) erected an artificial hill that replicated "the celebrated sites T A K E U C HI1 MA K I N G M O UN T A I N S

- 18. of the universe," including the canonized scenery of the region around Lake Dongting (one of China's hallowed views)., The motivation was not re-creation but sympathetic magic. Multiplication and reduction often accompany substitution and replication. The original Buddha Sakyamuni becomes the Thousand Buddhas, cursorily delineated on sanctuary walls from Ajanta in India to Dunhuang in China. Asian religious praxis, particularly Buddhist, is also filled with examples of shortcut/optimal-gain rituals: to give but one example, in many Buddhist countries worshipers can twirl a prayer wheel (called a chorten, a kind of virtual-reality circurnambulation technology) round and round in lieu of actually walking around the stupa. Each rotation, accomplished in seconds, is the equivalent of an often arduous physical circuit. Merit multiplies geo- metrically. Yet proliferating and abbrexiating something diffuses its original impact. This no-muss, no-fuss approach to salvation has a curiously postmodern feeling to it. Prior to the appearance of reduced-scale replicas of Mount Fuji, other kinds of symbolic equivalence played a role in its worship (as they do in religious practice in general). According to the preface of a printed version (dated i6o7) of the medieval Take of Fuji's People Catvrn (Fuji no hitoana zoshi), simply reading the tale, which describes religious experiences of transfor- mation in the Hitoana ("People Cavern"), one of Fuji's caves, counts as much towards salvation as the act of climbing the mountain itself.4 Even texts, then, can substitute for deeds. Assertions like this were often tinged with economic self-interest, but devotion and economics are sisters. The purpose of the preface was simultaneously to promote the tale and encour- age sales. Even bathing in an urban replica of one of the purification huts at the shrines at the foot of Fuji, a costly activity, was deemed to confer merit comparable to an actual ascent. Questions of simulacrum and substitution in Asian culture, then, invoke many dynamics, some otherworldly, others worldly, operating simultaneously. As contemporary Westerners, we need to set aside some deep-rooted as- sumptions about the value and propriety of replication and ruminate on more chthonic notions of the transmutability of physical stuff. FUJI CULTS AND THE LANDSCAPE OF FUJI The Suruga Fuji's sheer physicality pushes to the limit our ability to com- prehend the colossal. Its enormous yet readable scale, combined with the lack of vegetation and its stark geometry, elicits unsettling sensations of antlike vulnerability. The rocky austerity of the mountain affords few of the protective amenities of the prospect-refuge environment which the human species is said to be biologically programmed to prefer.' The soaring peak touches the skies: the mountain's head is often literally in the clouds. Fuji offers a space between heaven and earth, a liminal zone where divine and earthly beings commingle. Permanent yet ever-changing in different condi- tions of light, time of day and season, it seems alive. The plume of smoke it emitted during much of its geologic history led to the practice of offering incense to divinity in the hope of bridging the terrestrial and celestial zones., I5M P R E S S I 0 N S

- 19. Fig. 3. Katsushika Hokusai. The Over the long course of time Fuji accrued a massive dossier-a "mount- Formation offt4ount Hoei, from One ography" one might call it--of literary, political and religious history This Hundred Viens of Fuji (Fugaku h•akkei), comprises a voluminous literature, starting with poems from the eighth-century %ol. 1. 1834. Noodblock-printed book. 11anr'yoshu, themselves reflections of earlier thought. By the mid-nineteenth 22.5 x i 5.6 cm approx. each page, century, when Hiroshige depicted the Mini-Fujis under discussion, the Suruga Spencer Collection, New York Public Fuji was a heavily coded, one might even say overdetermined, piece of real estate. Library, Astor, Lenox and Tildcn Foundations Death and destruction figured among the various meanings linked to This last recorded eruption of Fuji took Mount Fuji. During Japan's long history its eruptions, which rained lava, place in 1707. ash and cinder over huge areas of the countryside, repeatedly brought di- saster to the farming communities in the enVirons. Placating it was a high priority in the religious and political sectors: Fuji's (leity was accorded court rank in the ninth century in an effort to cajole the volcano into qui- escence. The Formation of Mount Jioei by Katsushika Hokusai (176o-1849), from his One Hundred Vieus oj Fuji, shows Fuji's terrible destructive powers (fig. 3). This last recorded eruption of Mount Fuji took place in 1707, be- fore Hokusai was born but within living memory in his time. In keeping with the linkage of Fuji and death, one of the earliest extant images of the mountain shows it as a place of suicide. In an episode from the famous Lip of Priest Ippen scrolls of 1299, the lay monk Ajisaka drowns himself in the Abe River in the shadow of Mount Fuji.' Fig. 4. A collective giave at Motornura,iama in Fuji City Photograph. Death, however, as Ajisaka's final act implies, brings the hope of rebirth/ From Riji, special issue of Bessutsu nivo, salvation. Immortality looms large in the complex, sometimes contradictory no. 44 (winter 1983), 138 lore surrounding Fuji. Cultic beliefs incorporate Chinese Daoist legends TA K E U C H I MAKING N M O LI NTA I N S

- 20. Fig. 5. Katsushika Hokusai. Circling the concerning the elixir of immortality concealed within its summit. Prior to Craterof Fuji, frorn One Hundred tiei,n oJ the modern age, when there was no standardization in the characters used Fuji (Fugaku hyakkei), Vx)]. 3. 1834. for Japanese names, "Fuji" was sometimes written with two characters 'Aoodblock-printed book. 2 2.5 X i 5.6 cm meaning "Not" and "Death": deathless life, that is, immortalitx. The collec- approx. each page, Spencer Collection, tive designation for these cults that centered on mountain worship is New York Public Lihrari, Astor, Lenox Shugendo. Cultic practices included stringent rituals of fasting, meditating, and Tilden Foundations praying, chanting mantras, ringing bells and hanging over cliffs in order to achieve the supplicant's spiritual goals. Worshipers assumed white clothing for the climb (as they do today), white being the color for dressing a corpse, and they wore their hair unbound, in corpselike fashion. Pilgrims thus carried on their very bodies the mark of death necessary to achieve svmbolic rebirth. Those who ascended Fuji subjected themselves to potentially grueling physi- cal and mental ordeals. People climbed prepared to lose their lives. Figure 4 is a photograph showing a muenzuka (literally, a tomb for those with no con- nections), a collective grave for the numerous anonymous casualties of the mountain-a pilgrim's equivalent of the Tomb of the Unknow,,n Soldier. Aside from the danger of being bloNvT to bits in an eruption or being caught in an avalanche, unexpected storms could bring instant, or lingering, death. During circumambulation of the formidable summit, climbers who put a Fig. 6. Caldera on Mount Fuji, 1902. foot wrong on the rocks faced a drop of 8 2o feet into the caldera (figs. 5, 6). Photograph. From lFui, special issue of Certainly, the ascetic practices of fasting or poising motionless (sometimes Bessatsu Ta1ivc, no. 4-4 (winter 1983), 136 naked) in the elements contributed to many deaths. In addition there were I N1 1) R F S S I 0 N S

- 21. psychological perils. It was believed that climbers who ventured into this nether zone could be set upon by the innumerable malevolent spirits lurk- ing in the mountains; these would be all the more terriI,ing because they represented the terra incognita of the psyche. Fuji's religious history is long and complex. Vlhat follows is a brief synopsis, the purpose of which is to orient the reader rather than present new intbrmation.9 Shinto, Buddhist and a mishmash of popular faiths all claimed the mountain as their own. In Fuji the rich lore of many traditions coalesces. As was usual in mountain worship, Fuji's (e]ity was seen as female, an ironic inversion of the fact that women were forbidden to climb the sacred mountains. She was a syncretic deity, called by various names: Asama Daimy0jin, Asama Gongen, Sengen Daibosatsu or simply the generic Daigongen. After the separation of Buddhist and Shinto faiths during the Meiji period (i 868-i 912), the deity came primarily to be known as the goddess Konohanasakuva-hime, a properly Shinto-sounding name. As was the practice in portraying such goddesses, she was pictured as a resplendent court lady (fig. 7). When the Esoteric Buddhists appropriated Fuji's deity, they linked her with the Bud- dha of Essence, Dainichi, giving the mountain a male as well as a female aspect. This undoubtedly relates to the Chinese cosmological system, which genders mountains masculine 0yang) and valleys feminine (yin). Fuji's caldera was designated as having eight peaks (which in reality it does not), each corresponding to a petal of the Womb Mandala. The paradises of other deities, including Amida, Yakushi and Miroku, were mapped onto this mandala and joined the paradise of Dainichi on the summit. The mountain also played host to myriad other godlings, spirits, demons and souls of the dead. It teemed with unseen, unknowable presences. Just as the peak of Fuji was home to different paradises, its many caves were considered secret passageways to various hells. The People Cavern (men- tioned above) in particular possessed a rich mine of lore and legend. Tales were told of famous historical personages having transformative visionary experiences as they penetrated this symbolic entrance to the underworld. The caves, of course, were also explicitly associated with the womb. Pilgrims Fig. 7. KIatsushika Hoku.ai. The Goddeos entered them and conducted rituals in order to die and be reborn. These are refFuji, Konohanasaktu-himne (Princess of but some examples of the relentless application of shifting male and female the Flowering of TrIce Blossoms), from sexuality to natural phenomena. One Handred bew offhj (Ftiquku hyakkei), No]. 1.I 834. Woodblock-printed book. Although it is difficult to separate legend from history, documented cultic 2 2.5 X i 5.6 cm. Freis Collection ascent of Fuji had begun by the twelfth century, once a spate of disastrous eruptions in previous centuries had subsided. Votive sutras dating to the mid-twelfth century excavated on the summit represent the inscription onto (and into) the mountain of a record of people's religious aspirations in an age when it was feared that the Buddhist law would be lost.' During the subsequent medieval period a base for climbing Fuji was located at the Sengen Shrine in Muravama on the southwestern slope, which controlled access to the mountain. Because of fees and donations, the Murayama Sengen Shrine became a flourishing enterprise and its priests correspondingly powerful. After the seat of government moved eastward to Edo in the early seven- teenth century, a new kind of Fuji worship emerged: it consisted almost 30 TA K E U C H I MA KING MNIOU NTAI NS

- 22. exclusively of lay people-mostly merchants, artisans and farmers. The mountain provided a splendid new identity for the metropolis, whose lack of historic sites was sorely felt. Kyoto might have Mount Hiei and other natural and fabricated nostalgic places, but for sheer visual impact nothing could rival the Suruga Fuji, which could be seen from the city proper. It was quickly enfolded into the rhetoric of identity by different sectors of society. The founder of this new populist movement, Kaku• o Tobutsu (0 541- 1646), was a charismatic mountain ascetic from Nagasaki who proselytized in Eastern Japan.'2 As his dates suggest, Kakugy6 seems to have discovered the secret of longexity in his mystical union with the deity of Fuji: he died at the age of i o 5. Like many other supplicants, KakugyO performed the standard ascetic practices on Mount Fuji such as fasting, standing naked in the cold and bathing in icy water. He is said also to have meditated in the People Cavern for a stretch of one thousand uninterrupted days. He en- gaged in the yogic practice of poising motionless for long stretches of time and standing on tiptoe on a vertical beam (physically acting out the concept of replicating Fuji as the central pillar of the universe) in the attempt to entice the deity to enter his body: " Kaku-6 was believed to have the power to cure illness, and he was mobbed as a faith healer. His cult used the northern entrance to the mountain at the locality of Yoshida (revealed to him in a dream as the most efficacious route), and this brought him into conflict with the Murayama faction, which tried to monopolize access from the south; religious dreams have traditionally been a means for contesting authority The priests of the Murayama faction never entirely relinquished control, and as we shall see, they sometimes interfered with the new cult. The type of Fuji worship founded by Kakugyo consisted of Fuji-ko, or Fuji associations. At their peak it was said that there was one association in each block of Edo. These mutual assistance groups (ko), some religious, some fra- ternal, were (and still are) a prominent feature of Japanese society beginning in the middle ages. The Fuji-ko constituencies (or confraternities) even pooled funds so that all able-bodied (male) participants could make the climb. The Fuji associations proliferated during the tenure of the colorful sixth leader, the oil merchant and visionary' Jikigyo Miroku (1 671-1733), even- tually' garnering an estimated 70,00o members by the late Edo period.14 It was Jikigy who had the idea of constructing urban replications of Mount Fuji of the type seen in Hiroshige's Hundred i$ei's. JikigyO appears to have been something of a religious zealot, to the point of irritating even his own followers. In his fervent visions the deity of Mount Fuji revealed what became the core of the Fuji cult's "philosophy" It cen- tered on the connection between Mount Fuji's deity and rice, an idea that was in fact very ancient and based on the relationship between mountains and agriculture.' Mountains being the source of water, they provided the spiritual essence that made the growing of rice possible. By ingesting rice, human beings became absorbed into the deitx' Because the members of the four classes all eat rice--although the lower orders were supposed to be content with cheaper grains-Jikigy6 reasoned that there was no essential difference among human beings. (This was but one of many unorthodox I M 1 R F S S I 0 N S ) I

- 23. Fig. 8. Artist unknown. Airoku 2,1andala. Hanging scroll. 5o x 6o cm. From Tup, special issue of Bessatsu Tai,0, 110. 44 (winter 1983), 86 3 2 ~~~T EU C AK HI NI AK I NG N10U N T AIN S

- 24. Fuji-cult notions that the authorities of the Tokugawa regime, committed to keeping the classes separate, found uncongenial; soon after Jikigy6s death, government officials issued successive proclamations banning the Fuji-ko.) Jikigy6's name literally means "the practice, or religious protocol (gy6), of eating (jiki)." He also claimed that the deity of Mount Fuji directed him to adopt the name Miroku, pronounced with the same sounds as the name of the Buddha of the Future, although written with different charac- ters. There was another Miroku, a folk god who took care of humanity in times of famine, so Jikigyo picked a name with many potent associations." Jikigyo, who was only marginally literate, wrote the name Miroku with characters of his own deevising, claiming, again, to have had these revealed to him by the deity of Mount Fuji herself.' In 173 3, the year following the Kyoho Famine of 73 2, Jikigyo sacrificed himself in order to ensure an abundant harvest after the hardship of the preceding year, although he had been making plans for this deed for some years. In the sixth month he ordered a three-foot portable shrinelike hut to be carried to the Hat Rock above the seventh station of Mount Fuji. Al- though he would have preferred to die on the summit, the rival Murayama faction would not permit it. So he fasted at the Hat Rock for thirty-one days until he died. During this interval Jikigy6 dictated his final visions-no doubt made the more fervent by increasing lightheadedness-to a disciple. Upon Jikigyo's death, the disciple piled up stones to convert the shrine containing Jikigy6s body into a tomb. Jikigy-o thus achieved his aspiration to become physically united forever with the mountain. A mandala unique to the Fuji cult, desiglned to visualize Jikigy6's cosmology, shows Jikigy6 at prayer at bottom center, his head unshaven in the manner of a confraternity layperson (fig. 8). Balancing him at the top on the central axis is a triad of Buddhist deities (probably Amida w,ith Seishi and Kannon) hovering over the tripartite peak. The sun and the moon (symbols of the Diamond and Womb Worlds), which along with the stars play a prominent role in Jikigy0's eschatology (as they had in past mandalas), flank the Bud- dhist deities. In the middle of the composition, rising from cloud-swathed peaks, is the stone stele found near the fifth of the ten stations on the climb- ing route, marking the horizontal boundary between earth and heaven. The stele is inscribed in large characters "Daigongen," one of the names of the Fuji deity. Flanking the stone marker are the customary long-nosed, winged demons (the large tengu and small tengu), devious creatures thought to inhabit mountains and bedevil humans. An image like this would have hung on the altar (luring a Fuji cult service, although Jikigyo himself preached that images were not necessary in order to receive the bounty of Fuji.' Fortunately his instructions were not widely observed or we would not have the legacy of visual imagery that helps us better to understand this cult. Reconstructions of the altars used in the rituals also illustrate some of the cult's beliefs and practices (figs. 9, 1 o). The leader of each association kept a portable altar in his residence. Since the location of meetings rotated among the membership, the altar could be set up as needed. The associations gathered monthly to participate in ceremonies that included lectures or sermons, chants and prayers in front of the portable altar, burning torches I M I 1I. F S I 0 N S

- 25. Fig. 9. Altar of the fokwo Adachi Ward Avase Sanp&-maiiufuchi ratrnitN- 0iy.< 18277, mioder-n r-eco[nstruction. From fuji, special issue of Bessatsu Taiyo, no. 44 (villter 1983), 86 00< Fig. io. Altar of the Tokyo Itabashi Vard Nagata Fraternity. 18 5 5, modern recostr uction. From Fuji, special issue of Bessatsu Tai&5, no. 4-4 (-Minter 198 3), 86 and eating a meal cooked over an open fire (this element being associated Sfwwith volcanoes)." As is clear from a comparison of the two altars in figures 9 and i o, there was little standardization in the ritual paraphernalia necessary beyond candles, vases with floral offerings, a sculpture of Fuji and a hanging scroll inscribed Aith the spells chanted to invoke the deities. These scrolls display the special characters invented by the cult leader-a kind of "writing in 4! tongues." The lack of standardization underscores the loose organization of the confraternities. The independence of the various chapters is further suggested by the presence of each association's crest on its paraphernalia. The more elaborate altar of the Awase Sanpo-marufuchi association (fig. 9) is furnished with a triptych combining a scroll of the mantras with their special characters at left, an image of the Fuji goddess in the center and at right an abbreviated version of the Miroku Mandala seen in figure 8. It has a miniature Shinto shrine gateway equipped xwith the traditional folded paper and straw rope. In the center of the altar on a table stands an ex- traordinary mirror, a traditional Shinto symbol of divinity. This mirror is set into a naturalistically sculpted Fuji (complete with the bump that ap- peared after the eruption of I 707), on whose slopes waft clouds support- ing the traditional sun and moon at right and left respectively. Where the slopes become foothills are two monkeys, hands clasped in prayer. These whimsical creatures are there because, according to Fuji lore, the mountain appeared in the koshin ("Elder Brother Metal Monkey") year of the 34 TAKEUCHI MAKING MOUNTAINS

- 26. sexagenary cycle; a monkey god named Sarutahiko was included in Fuji wor- ship. The form of Fuji in the simpler altar of the Nagata confraternity follows the more archaic, stylized three-peak shape (fig. i o). These altars show how Fuji-ko worship combined aspects of Shinto, Esoteric Buddhism, mountain cults and popular folklore. From the prominence accorded the beautiful female defty, it is clear that the feminine as an object of desire played a significant role in Fuji's gendered landscape. The reverse, the feminine as an object of loathing, obtained equally strongly. The pervasive culturally sanctioned misogynism that kept women out of sacred space was officially written into the religious and political ideology of traditional Japan (and most of Asia, for that matter). A text dated 18 , for example, describes the raison d'&re of the popular Buddhist 82 Menstruation Sutra (Ketsubon-kyo), one of China's gifts to Japan: All women, even those who are the children of high families, have no faith and conduct no practices, but rather have strong feelings of avarice and jealousy, These sins are thus compounded and become menstrual blood, and every month this flows out, polluting the god of the earth in addition to the spirits of the mountains and rivers. In retribution for this women are condemned to the Blood Pool Hell." Whereas in Confucian tradition women were flawed because of their per- ceived weakness of character, in both Shinto and Buddhist belief their infe- riority stemmed from biological causes as well. Blood, undoubtedly owing to the stain it leaves, constitutes a very serious form of pollution. Women, because of their potential for defilement (even when not actually menstru- ating or giving birth), could unpredictably inject impurity into the natural world and thereby bring divine wrath on human affairs. When, for ex- ample, heavy rains threatened to spoil the crops in 18oo, a special "good karma" year when women were allowed farther up the mountain than usual, local farmers attributed the bad weather to the presence of the fe- male pilgrims and successfully petitioned for a stop to their dangerous pro- fanation of sacred space.2 ' On the face of it, women were unlikely devotees of mountain -climbing cults. But religious establishments made increased efforts to accommodate the biologically disadvantaged half of the popula- tion during the Edo period-a classic case of entrepreneurship in which a need is created and then addressed by the same party The primary boon that the deities of Fuji and other mountain cults offered women was a predictable one, namely, procreation. Fuji's Sengen Shrines did a brisk business in the sale of safe-childbirth talismans, to be carried in a woman's obi for the duration of her pregnancy Wealthier or more fer- vent devotees could bux sanctified sashes to wear during pregnancy"' It is likely that these lucky objects were bought at the shrines by Fuji-associa- tion husbands as souvenirs for their stay-at-home wives. If a woman were particularly energetic and devoted, she too could make a pilgrimage to Fuji. In a normal year women would be allowed, after seven- teen days of purification (more than the time required for men), all the way to the second, and sometimes to the third, of the ten stations. The optimum opportunity for women's salvation occurred once every sixty IMPRESSIO NS 24

- 27. Fig. ii. Katsushika Hokusai. Group years, during the koshin combination in the sexagenary cycle discussed Climbing the lountain, from the series above. According to Fuji lore, it was in the koshin year traceable to 2 8 6 B.C. Thirq-Six Viens of',Mount Fuji. Early that the mists parted and Fuji's form miraculously appeared. Climbs dur- 18 3os. Color woodcut, iban. Courtesy ing the koshin years (the so-called goen nen, "[good] karma years") were Sotheby's, London touted as being sublimely efficacious. A climb during a good karma year was worth thirty-three climbs in ordinary years. During these years (unless special circumstances, like the heavy rains of i8oo, interfered), women flocked to climb as far as the "rvonin kekkai" (women's off-limits), located between the fourth and fifth stations. There they were welcomed by the nyonin oitate kekkai, literally the "driving-women- away barrier."' At what point does ritualized gendering of landscape elide into questions of sexualization? Fuji's Womb Cave and the practices associated with it blur that boundary. Much has been wTitten about the telescoping of the notions of entering a cave and entering the womb, thus to be reborn, in Carmen Blacker's lovely phrase, "by the mimesis of symbolic action." This is certainly not unique to Fuji-cult thought. From Daoist to Shugendo writings one finds explicit linkage of caves and wombs.2 4 Hokusai's Group Climbing the M1ountain, from his series Thirty-Six Vicls of Mount Fuji, shows white-clad pilgrims curled in the fetal position literally enacting this pro- cess of rebirth (pl. 3/fig. ii). Not only would pilgrims enter the womb to be reborn, they would also nurse at the breast of the Great Mother. This too has counterparts in Daoist lore, which likens the cave's stalactites to the "bell teats" of Holy TAKEUCHI IMAKING MOLINTAINS

- 28. Fig. 12. Hashimoto Sadahide (1807- 80 1873). Pulgrims in the 0h6nib Cave on Mount Fuji (detail of Amida Cave) 1857. Color woodcut triptych, Oban. 3 5.4 x 24.4 cm each. D. Max Moerman Collection. Photo: John Deane See Pl. 4 for full triptych. SMother Earth, thought to secrete a nourishing essence (pl. 4/figs. L2, 13).2' h When a grown man suckles at the breast, that act takes on erotic overtones; womb elides with vagina. Since entering the womb and penetrating the va- 741, gina are operations wholly difterent in nature, the erotic implications of sucking the Womb Cave's stalactites cannot be denied. It is hard to imagine how this topographical feature could serve the spiritual needs of women or how women might feel participating in such a ritual. The enactment of re- entering the womb and nursing at the breast would have very different psy- Fig. 13. Stalactites in cave on Mount F'uji. chological nuances for the two sexes. Photograph. From luji, Special issue 01f Bessatsu TThyo, no. 44 (winter 1983), 1 33 MOUNT FUJI IN EDO If women, the weak-bodied, children and the aged were excluded from full participation in the rituals connected vith the Suruga Fuji, replication pro- vided a solution for their salvation. In the spirit of the inclusionist trend of Edo popular religion in general, the Mini-Fujis managed to accommodate those whom the sacred peak itself couhl not. 7 It is here that men's and women's devotional practices overlap to the greatest degree. Physically replicating NIount Fuji for ritualistic purposes was not a wholly new phenomenon. Starting in the fifteenth century, a few Sengen shrines (that is, shrines dedicated to Sengen, another name for the Fuji deity) had been built on eminences, mostly old burial mounds. The Sengen Shrine at Komagome in Edo, pictured in the Record of Edo's Famous Places (Edo I N1 P R I S 5 I 0 N s

- 29. Fig. 14. Artist unknown. Fuji Sengen Shrine at Komoaome in Edo, from Record - Edo's Famous Places (Edo oeishoki), vol. 2. r 66 2. Woodblock-printed book. s" 2 6 x 18.3 cm. Spencer Collection, New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations meishoki) of 1662, exemplifies this older configuration (fig. 14). It differs from the later Mini-Fujis in a number of respects. A straight stone stair- case leads directly to the shrine at the top. The designer makes no attempt to duplicate the process of climbing Fuji, to copy the switchback trails to the summit or to incorporate Fuji's famous landmarks. Sengen Shrines conducted festivals connected with the opening of the Suruga Fuji's climb- ing season, and it is possible that with time the general populace did not differentiate between the new cultic Mini-Fujis and the older forms such as that at Komagome. We will return to this point below By way of explaining the motivation for the creation of the Edo Mini-Fujis, the Jiiscell,neous Historv'oJippoan (Jippoan yureki zakki, i 8o4 8) states: Mount Fuji is so high that even in the case of men, those with a weak heart fall ill because it is difficult to climb a 0o-ri mountain. How much harder then is it for women with their defilements and many obstacles! And it is arduous also for the verv voung anti the old to climb Fuji. Feeling sorry for these people Ch6jiro [sic] had the sincere wish that exeryone would be able to climb the mountain, and he made a copy of it so that men, women, young antI old could set their hearts at peace.' The Chojiro men-tioned in the account was a follower of Miroku Jikig6 named Takata Toshiro (religious name Nichigy6 Seizan, 170 5-1 782). A gardener by trade, Toshiro is said to have climbed Fuji seventy-three times, although this may be part of the hagiography that quickly enveloped many T A K E U C 1I-: M A K I N (I M ( Ll N T A I N S

- 30. Fig. iS. Utagawa 1-firoshige 1I. Takata: cult leaders. To commemorate the thirty-third anniversary of Jikigyo's Takata Fuji, fi-om Picture Book of Edo death in 1765, T6shir6 decided to build a "Fuji utsushi," or, in Henry Soulvenirs (Ehon Edo nimage), vol. 8. 1861 Smith's phrase, a "transferred Mount Fuji," in keeping with Jikigyo's Color " oodb lock- printed book. Wishes.2' In 1779 Toshiro and some disciples began work on a mound six 14.6 x 18. 1 cm. C. V Starr East Asian meters high in the Mizu Inari Shrine in the precincts of the Tendai temple I ibrary; Columbia UniversitN, Nex Hosenji at Takatanobaba in Edo (fig. 15). Like the older Fuji Sengen "•ork Citv shrines, Toshiro's Fuji seems to have had an ancient burial mound as its base. Because T6shir6 lived in the Takata area of Edo, his "surname" (as was often the case with commoners) reflects his area of residence. His mound thus came to be called the Takata Fuji. To imbue his Mini-Fuji with authenticity, Toshiro used black volcanic rock transported from Mount Fuji for the upper part of the structure. He also furnished his miniature with Fuji's legendary sites: the Womb Cave, the switchback route consisting of nine "turns" with markers for each of the nine stations, the Sho Ontake Shrine at the fifth station along with the gir- dling road called the Ochudo (the midway circuit marking the boundary between heaven and earth), the Hat Rock near the seventh station and the Okunoin Shrine at the top. By including the Hat Rock, the site of Miroku's self- sacrifice, Toshiro fused religious lore and historical personality. In similar fashion a statue of Toshiro himself was used in the opening ceremo- nies (yanibiraki)of the Takata Fuji. It would seem that the charismatic per- sonalities of various association leaders were embedded into the fabric of cultic worship-they became folk deities themselves. Toshiro, who died a I M P R E S S 1 0 N S 39

- 31. Fig. 16. Hasegawa Settan. Pilgrimage at mere three years after the construction of the Takata Fuji, arranged to be 1hip Sengen Shrine at Komugome, fi-or buried at the foot of his creation. Guidebook to Edo's famous Places (Edo The Takata Fuji was supposedly open to the public for climbing only (lur- lislho zuc), Vol -. 185--34 36. 'oodblock-printed book. 26 x [ 8.3 cm. ing the time that the "mountain opening" ceremonies for the "real" Fuji Spencer Collection, New York Public took place. This varied friom the end of the fifth lunar month to some time Iibrars, Astor, Lenox and Tilden after the middle of the sixth. The inscription on the guidebook image in Foundations figure 15 reads: "Takata. Fujisan. This is located in the Takata H6senji Mizu Inari compound. It is unlike the other Fujis. Pilgrimage goes on till the eighteenth day of the sixth month. Snakes made of straw are sold. "Teashopsand other enterprises appear. This continues for several days." The observances held at the Mini-Fujis seem to have overlapped with an- nual festival customs already in place at the older Fuji Sengen shrines like the one at Komagome. An illustration by Hasegawa Settan (1778- 1843) from the 1834-36 Guidebook to Edo's Famous Places (Edo ineisho zue) shows the festive pilgrimage that took place annually at the Komagome Sengen Shrine around the first (lay of the sixth month (fig. i6). Throngs of fash- ionably dressed people of all ages, samurai and commoner alike, worship, sightsee, buy, sell and stroll. In addition to the straw snakes, fans and five- colored string bags noted in the caption (many of the same festival souve- nirs listed for the Takata Fuji), there are tea sellers, watermelon vendors and people selling dried fruit and grilled delicacies on skewers. ' I have not come across any illustrations of a Mini-Fuji showing anyone wearing the TAKEUCHI MAKINC( MOUL]NTAINS

- 32. white pilgrims' garments described in the texts. Those climbing wear the everyday clothing of sightseers. That large numbers of the Edo populace came to consider the Mini-Fujis as part of the enormous annual round of observances that guided them through the seasons is clear from the example of the scholar Saito Gesshin ( 804-1 878). Gesshin, the third generation of a family of writers who had compiled numerous monumental guidebooks such as the Record of Annual Events of the Eastern Metropolis (Toto saijiki) of 1838 and the Guidebook to Edo's Famous Places, seems to have made a business of attending as many seasonal events as was humanly possible-sometimes several in one (lay. Detailed knowledge of local customs was, of course, mandatory for the author of a thirty-eight-volume account of the annual events of Edo. Although Gesshin cannot be made to speak for all Edoites, his comprehensive polytheistic approach seems fairly typical of the dominant premodern (and even mod- ern) style of worshiping whatever deity claimed center stage on a given oc- casion, in a gregarious, communal celebration. The Mini-Fujis did double duty as festival and entertainment sites as well as serving as a focus for Fuji-ko devotionalism. Gesshin's Record of the Annual Events of'the Eastern Metropolis mentions at least fourteen other Edo Mini-Fujis that had come into existence (luring the half-century since the creation of the Takata Fuji. I He ends his list with the remark that these mounds had recently become quite popular. Gesshin himself attended the Fuji "mountain opening" festivities at Komagome, Kayacho and Yanagihara. At the end of the fifth month he also went on a pilgrimage to climb the "original" Fuji in Suruga."4 Given the documented popularity of Edo's Fuji cult and its mounds, the image of the 'akata Fuji in the 18 5o-67 ten-volume Picture Book of Edo Sou- venirs (Ehon Edo miyage) by Hiroshige and Hiroshige 11 (1826- 869) shows a curiously denatured scene (fig. i 5). Even though the seasonal teashops indicate that this is the Tlkata Fuji at peak tourist season, so to speak, the handful of tiny figures of men and women is at odds with the image of thronging celebrants so vividly described in other sources. It is possible that common models existed for the depiction of Edo's fa- mous sites and that artists freely borrowed and adapted them. Consider, for example, a comparison of two renditions of the Mini-Fuji located within the precincts of the Fukagawa Tomigaoka Hachiman Shrine. One is from the Record of Annual Events of the Eastern 41etropolis, compiled by Gesshin, illustrated by Hasegawa Settan and published in 18 3 8, the other from the Picture Book ofEdo Souvenirs (figs. 17,18). Each employs the same general composition: the mound, anchored at left, is viewed from such an elevated perspective that the viewer can see over its summit, over city roof- tops and a large body of water, to distant mountains behind. The illustra- tion by Settan teems with people of all ages jostling each other on the nar- row path (fig. 17). It accords with the written descriptions of the Mini- Fujis as popular pilgrimage sites. There is no Suruga Fuji on Settan's hori- zon. Although the caption from the Picture Book of Edo Souvenirs describes the "mountain opening" days and the sideshows that accompany them, I t, P R F 5, I 0 N S ?

- 33. Fig. 17. Hasegawa Settan. Hachinan there are only two couples participating in this lonely spectacle (fig. 18). The Shrine at Fukayawa Tomigaoka, from artist seems to have been more interested in illustrating the part of the inscrip- Record ofAnnUal Events in the Eastern tion that describes the distant views from the summit, which includes mention Metropolis (Tto saijiki), vol. 3. 18 38. of tie Suruga Fuji itself Possibly Hiroshige I and Hiroshige II both took the lib- Woodblock- printed book. 22.6 x i 5.9 erty of making a visual play between the real Fuji mound and the imitation Fuji, ckn. Hans Thomsen Collection as in figures i and 2. Were the Suruga Fuji actually visible from the Fukagawa Hachiman Mini-Fuji, it is inexplicable that Settan, under the direction of the ubiquitous, indefatigable and positivist Gesshin, neglected to include it. The third Mini-Fuji depicted by Hiroshige in his One Hundred Famous Views ofEdo is this same Fukagawa Tomigaoka Hachiman Shrine (pl. 5/fig. 19). Henry Smith draws attention to the ambiguity in the caption to this print- Fukayawa Hachiman vamabiraki-which he translates "Open Garden at Fukagawa Hachiman Shrine." It could also mean "Mountain Opening at Fukagawa Hachiman," although Smith believes that )yamabiraki (mountain opening) in this case refers to the annual opening to tourists of that shrine's famous old garden for a few (lays in the third or fourth month." Hiroshige thus played down the importance of this Fuji mound by depicting it out of season but with a few sightseers climbing it. As if to deemphasize further the garden's connection with Fuji worship, Hiroshige did not include the Suruga Fuji in the background. The Meiji Restoration did not put an end to the Fuji-k6. On the contrary, erection of the mounds seems to have reached a high point in the 189os.16 TA KE U CH I, MAKING MOUNTAINS

- 34. Fig. 18. Utagawa Ifiroshige II. But their popularity did not necessarily depend on their religious aspect. The Huchiman Shrine at tFukagjaia Tmiogaoka, thirty-three-meter Mini-Fuji in Asakusa (fig. 2o), built by an entrepreneur in from Picture Book o?fEdo Souvenirs (Ehon 18 8 7, stood in the newly created Asakusa Park in the company of music Edo miooage), vol. 9. j 864. Color halls, a movie theater and other up-to-date entertainments. Although an un- woodblock-printed book. 14.6 x 18.1 generous observer likened it to an apparition of a freshwater snail, fashion- cm. From Asakura I laruhiko, ed., able people flocked to it. It lasted only ten years before a typhoon damaged it "Nihonmeisho.fl-zoku zzzc (Pictorial beyond repair. compendium of the Japanese famous- places genre), vol. 3 (Tok-vo: Kadokawa A simulacrum of a natural landscape exposes underlying social formations. Shoten, 1979), 320 The various protocols assigned to the Mini-Fujis are a case in point. It is time now to put these into sharper focus. Bernard Faure has written that, "The world in miniature is said to call the powers of the macrocosm, which flow into it, fusing with it.",' While concentrating the manna of a large sacred form into a smaller one, the process of miniaturization also profoundly alters the nature of the copy: And once meanings are assigned, they slip. This process in turn opens up new areas of discursive meaning. Miniatures, for example, have been equated with the domain of the marginalized, and particularly with women, as Donna Haraway and Susan Stewart argue."s As simulacra the Mini-Fujis, unlike nature's more vulner- able original, become, ironically, undefilable sites. They are impervious to the blood pollution of the unclean. The presence of women, old people, the handicapped and the very young-society's more fragile members whose vulnerability may bring ritual pollution to everyone-cannot ad- versely effect the essence of these structures now under human control. IM PRESS IO NS 214 43

- 35. The process of substitution has conquered nature. Mini-Fujis are surrogates that receive and deflect defilement. The miniatures transform Fuji's "fearful syrtn- metrv" (to borrow Blake's phrase), revealed to the intrepid pilgrim episodicalN; segment by segment on the actual mountain, into something whose totality is immediately ap- A, i prehensible on a human scale. In a mini- pilgrimage to a Mini-Fuji, time and space, ritual and religious "reality" are collapsed. Miniaturization replaces narrative with tab- leau.s" The climber is able to participate and to bear witness at the same time. In hind- sight it seems almost inevitable that phe- nomena like the Asakusa Fuji would come to represent the ultimate conflation of the miniaturize(] pilgrimage with sheer enter- tainment. Hiroshige had a curiously, detached vision of Edo's Fuji mounds. Its marked difference from both the literary evidence and the bus- tling air given these sites by other artists suggests that a process of editing and omis- sion was operating. This decidedly reserved point of -iew invites us to contemplate the subjective nature of representation. Hiroshige, a man of minor samurai status, invests most of the panoramic scenes in One hludred Famous Views oJ Edo with an emotional distance and a Fig. 19. Utagawa Hiroshige. "Alountain sense of propriety. These qualities pervade his Picture Book ojEdo Souvenirs Opening" at Fukagawa t1achiman Shrinc, as well. It is as if Hiroshige set out to represent a xieNv of the city quietly fi-om the series One Hundred Tamous Views compatible with the Tokugawa notion of an ideal Confucian order. This ,J fEdo. 18 56-58. olor woodcut, oban. detachment distinguishes his later work from earlier scenes such as the 36.2 X 23.7 cm approx. Courtesy more lyrical series of 18 34 depicting the Tokaid6 Highway. Perhaps, as he Sotheby's, London aged, he became more conservative and decorous, as is often the case. Hiroshige was fifty-nine y,ears old (sixty by Japanese count) when he started the set, and he had just taken the tonsure. He may have had the sense that he was coming to the end of his life. He died just two years later, before the set had been completed. It is also possible that Hiroshige's "cool" representation of the Mini-Fujis had to do with the status of the Fuji cults in Edo society. Not everyone viewed this populist religious movement with enthusiasm. Perhaps Hiroshige's samurai sensibility put him in sympathy with the authorities, who saw the Fuji-ko as a social nuisance undesirable in an orderly society.4, It may not be a coincidence that the most severe edict against the cults was issued in 1849, the year before the first volumes of Hiroshige's Picture Book of Edo Souvenirs were published (and seven years before he began One T A K E U C H I MAKINCG MOLI NTAIN,S

- 36. Fig. 2o. Ikuei (Kobayashi Eijiro, active Hundred Famous Vieus of Edo). Hiroshige mayx well have considered the ac- i8 Sos). Asakusa Park: The Prosperit, o/ tivities of the Fuji fraternities with the distaste with which a High Episco- 4lount Fuji. 1 887. Color 0Woodcut, palian views a televangelist. ohan triptxch. From -U)ji,special isSLC o0 Bessatsu Tah,6, no. 44 (wxinter 1983), 90 Are the Mini-Fujis artificial landscapes, topographically mimetic gardens, instruments of devotional praxis, trivializing theme parks or dilutions of a sacred site? The answer is, they may be all of these. Whatever the explana- tion, Hiroshige's presentation of the Fuji mounds offers a nonstandard or alternate perspective on an important Edo-period phenomenon. An ex- amination of his Mini-Fujis demonstrates that while the One Hundred Famous Vieis"oj'Edo appears to be objective reportage, it still encodes the artist's own subjective vision of his times. E I NI P R E S S I () N 5 " I 4

- 37. Notes i. See, for example, the"MOUnit Akan Fuji" no ,anlaku shinko (Histors of the Fuji cult: Fdo and NIount YC(tei, known as the "Fuji of townspeople and mountain worship) (lbkvo: Hokkaido." There is also the "Satsuma Fuji" Mteiclxo, 1983). See also Royall Tvler, "A I would like to thank I lenry D. Smith 1I foir (Mount Kaimon) and the AizuAVakamatsu Glimpse of Mount Fuji in Legend and Cult," generously sharing his enormous stash of "Little Fuji" in Bandai-Asahi National Park. jonin-nal f the Associon of 7eather, ojuan,po,ise, material on Miii-Fujis gathered over mainy vol. 16, no. 2 (1981), l4o-65, and Henry 1). 2. For a synopsis of Western thinking on this years. A special debt of gratitude is expressed Smith 11, Hokusai: One 1-hindred Uems of'Aft.Filp issue, see Michael Camille, "Simulacrum," in also to Julia Meech, the most fiercely riigorous (New York: George Braziller, 1988). Robert S. Nelson and Richard Shift, eds., editor in history. Thanks are due in addition to Critical Terinsjfo Art Historv (Chicago and i o. For an example of this configuratio(n, see Christine Guth, Tom Iltare, Caroline Kakizaki, London: Unimersitv of Chicago Press, 1996), lecc, Reflections, fig. 93. SLIsan Matisoff, FLuMiko Miyazaki, David 3 -44. Moernian, Mikiko Nishimura and Suz,an1C i i. See, for example, a set of sutras executed Wright. 3. RolfA. SteCin, The IVrld in Aliniature: in ciinabar ink on paper in Nara National Container ("arens and Diiellings in Ihar Eastern Museum, ed., Saon aku shinko no iho (Relics of Rdigions Thlouqht (Stanford: Stanford University mountain cults ) (Nara: Nara National Press, 1990), 24. MuseuC11, 198 5), 110. 43. (Cinnabar is a 4. Mikiko Nishimura, "Circulation oflthe Fuji no substan e considered by Daoists to confMir immortality) It is said that the Buddhist monk hitoona zoshi and Its Influence on the Cult oi1Fuji Matsudai established a temple at the top of during the Medieval Period," seminar paperi Fuji and buried 5,196 sutras there in i, 149,; Stanford Univer-sits, 2 i. This tale, which is Nishimura, "Circulation of the Fuji no Hnoana thought to originate in the late Kaniakura or eailI 1ýshi"," [ 1. Muromachii period, was widely ciiculated during Japan's medieval period. Nishimura cites as hei f 2. For KakugyC, see Royall Tyler, "The source Koyama Kamunari, "Fuji I [itoana zoshi "li6kugawa Peace and Popular Religion: Suzuki kenkyuinooto" (Research notes on the luji Shosan, Kakugso Tobutsu, and Jikiý-vo Miroku,'" Hitoona zoshi), in Rissho daigakU kokugo in Peter Nosco, ed., Confiticianisn0 Tokngaioa and koknbunoakn (March i976 and March i978). The Cuhnmre (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton UniversitA notion that reading a holy text was equivalent to Press, 1984), 1011-9; Martin Collcutt, "Mouilt making an actual pilgiimage was not unique to Fuji as the Realm of IMiroku: The Transfor this work, but a fairly widespread helief. mation of Maitreva in the Cult of Mount Fuji 5. Mikiko Nishimura, "The Popularity of Fuji- in Iarlly Modern Japan," in Alan Sponbeqrg and ko and Its Influence on Image Production I lelen Hardacre, eds., Alonrew:a The Fbuinr during the Later Edo Period," serninar paper, Buddha (Cambridge and London: Cambridge Stanford University, i 3. These replicated huts Unliversity Press, 1988), 2 ý 3-59. were Popular in the Kyoto area but not in Fdo. 13. Carmen Blacker, The Catalpa Boi:A Stwudi ii" For the income generated by the sale of the Shanianistic Practices in Japan (London, Boston, white ritual clothing and xxalking sticks, and by and Sydney: George Allen and Un%xin, 1986), fees charged IOr climbing the mountain, 8 I o 3. Oin ascetic initiation and visionary purification services and lodgings, see and symbolic journeys, see chaps. 9-[ i. Nishimura, "Circulation of the 1-ilp no Hitoana zoshi," 1 3. 14. Martin Collcutt, "Mount Fuji as the Realn of Miroku," 256, citing Aizaxxa Seishisai's 6. Jay Appleton, The Svinbolisn of ila,itat:An Shinron of i 825. Interpretation of Landscape in the Arts (Seattle and London: UniversitY of VWashington Press, 1 5. One of the ancient etymologies of Fuji 1990), 15. suggested a mountain of piled-up rice. For infoirmation oni late-Fdo Fuji cults, see FLumiko 7. Although Fuji is dormant, it is not extinct. MiYazaki, "Emperor 0 or1iship and Fujido," 8. See Sherman F. Lee, Rflections of Realm JapaneseJournalof Reliqious SiudiCS, ol 1 7, u0s. (Cleveland: Cleveland Museum of Art in 2- 3 (June-Sept. 1990), 28 i-314, and cooperation with Indiana Univexisity Press, Mivazaki Fuiniko, "' Fuji no bi to shinko saiko' 1983), p1. Vi. iiinotoit in no shiten kara" (A reconsideration of 'Fuji aesthetics and worship' from the 9. Some of the key works on Fuji worship viewpoint of the locals), KAN, vol. 2 (surniner include Inobe Shigeo, E-uji no rekishi (Historv of 2000), i24 3i. Fuji), 5 vols. (-likvo: Kokon, 1928-29) and lwashina Koichiro, Eujiko no rekishi: Edo shoinin i t. For more about the conflation of the TAKEUCHI: MAKING MO4 t UNTAINS

- 38. deities, see Collcutt, "Mount Fuji as the Realm Stipas, Mandalas: Fetal Buddhahood in from Matsunosuke Nishivarna, Edo Culture: of Miroku," 259 6e, and Miyazaki, "Emperor Shingon," Japanese Journal of Reliqtous Studies, Daibs lije and Diversions at Urban Japan, i6oo- Worship," 287-88. Vol. 24, iios. 1-2 (spring i997), 1-38. s868 (Honolulu: University of Hawai'i Press, 17. The mi is written with the ideograph 1997), 80- 91. 25. Stein, The If arld in Miniature, i i o. meaning status, oneself, or one's person; the 33. The list given in Nishiyama, Edo Culture, 26. Helen Hardacre, "The CaVe and the Kenkyo-usha dictionarv gives the meaning ofroku 85-87, does not altogether match the one in Womb World," JapaneseJournalof Reliqipous as a fief stipend or ration [of rice]. Jikigyo is the transcription of Rewrd uf Annual Events oj the Studies, vol. io, nos. 2-3 (June-September indicating the link between the physical self Eastern Metropolis in Asakura, Nihon meishofazoiku 1983), 14 9-76, esp. 166-74. Hardacre's and the boUnty of rice. Mue,vol. 3, 148. The latter includes: Asakusa article centers on a contemporary Shugendc Jariba, Fukagawa Hachimango, Fukagawa iS. Iwashina Koichiro, "Edo shomin no Fuji ceremony of entering a cave at the Oku-no-in Morishitacho Shinmeigei, Teppozu Inari, shinko" (The Fuji worship of Edo commoners), Peak at Mount Omine, Nara Prefecture. Kayacho Tenmangu, Ikenohata Shichikench6, Fuji, special issue of Bessatsu Tag"a, no 44 27. The information in this section was taken Yanagihara 'Yanagimori Inari, Kanda Myojin (winter 1983), 96. from Henry D. Smith I1, "Fujizuka: The Mini- Yashiro, Kanda Matsushitacho uclo, 19. Cornelius Ouwehand, "Fujisan-the Mount Fujis of Tokkyo," Bulletin ofthe Asiatic Koarnichobori Inari, Shitaya Ono Terusaki Centre of a Nation-wide Mountain Cult," Socien, ofJapan, no. 3 (March i986), 2-5, and Myojin, Takanawa Sengakuji/Nyoraiji, Honjo SinssairGazette (October 1984), i 5. some unpublished materials provided by Mutsume and Meguro Gysninzaka. Oddl), Professor Smith; Iwashina Koichiro, "Takata Gesshin does not mention the laMkata Fuji. 20. Momoko Takemi, "'Menstruation Sutra' Fuji," Ashinaka, no. 38 (October 1953), 18-2 8; Belief in Japan," JapaneseJournal cflReligious 34. Nishiyama, Edo Culture, 87. and Iwashina Koichiro, "Tokyo no Fujizuka" Studies, vol. io, nos. 2 3 (983), 235. (The Fuji mounds of Tokyo), Ashinaka, no. i 48 35. See Henrv D. Smith 11's caption to no. 68 2 1. Iwashina, "Edo shomin no Fuji shinko," 95. (December 1975), i-26. in Hirishise: One Hundred Fanious ie is ofEdo (New York: Braziller, 1986). 22. For a reproduction of such a sash, see Fuji, 28. Iwashina, "Takata Fuji," 23. special issue of Bessatsu Toapa, no. +4 (winter 36. Henry D. Smith If, unpublished chart. 29. Smith, "Fujizuka," 3. 1983), 76. 37. Bernard Faure, "The Buddhist Icon and 30. f-ianscribed in Asakura Haruhiko, ed., Nihon 23. It was not until 1872 that the Meiji the Modern Gaze," Critical hIquir Vol. 24, tneissosuzoku zue (Pictorial conmpendium Of the government lifted this ban, and women were no. 3 (spring i998), 799- Japanese famous-places genre), vol. 3 (Tokyo: allowed all the way to the summit. Miyazaki, Kadoskaxa Shoten, 1979), 3 i o. Since Japanese 38. See Donna Haraway, "A Cvborg Mantifesto: "'Fuji no hi,'" i 26-29, gives an account of the does not diff erentiate between singular and Science, `echMology, and Socialist-Feminism in Various struggles by women to climb Fuji and plural, the statement "It is unlike the other Fujis" the Late Twentieth Century," in Donna the strategies employed by the local farmers could also read "It is unlike [the Suruga] Fuji." Harassay, (jvborys, Siunans and l'Faien: The and pilgrimage leaders to keep them out. In Reinvention of Nature (New '•oik: Routledge, 183 2 the first woman, accompanied b) five 3 1. These items became standard commodities 199 1), i 4 9-8 f. See also the chapter on the men, climbed secretly to the top after the for sale at Fuji shrines. Carried by women with miniature in Susan Stewart, On Longing: official season for climbing had closed. After a children, fans, bags of cancy and straw snakes Narratives ofthe Miniature, the Giqantic, the sufficient number of women had ventured attached to sprigs of bamboo appeai, foi Souvenir, the Collection (Durham, N.C., and beyond the permitted boundary, local officials example, in a triptych by Utagasa Kunisada London: Duke University Press, 1993), 37 69. erected a sentry station. Many mountain- (1 786--i864), ShoaVer on the lKy Honiefrom the crashers were apprehended in the years between SixthAfonth Fuji. See JeizO Suzuki and Isaburo 39. Stewart, On Longing, 56. 183o and f s50, but many more successfully Oka, ,1asstet,vorks sf Ukivoe: The Decadents 4o. See Smith, "Introduction," Hiroshige: One used side routes around the barrier. (Tokyo, Ness York and San Francisco: Kodan- Hundred Iaous n1oieivs, 10. sha International, 1982), figs. 1 3-I 5. I am 24. See, for example, the phraseology of the 41. Proscriptions against the cults started grateful to Ellis Tinios for this reference. appearing in public documents beginnino in Japanese Shugendo master S7th-century Gakuhis, who describes the experience at 32. For example, see nos. 2952, 2953, 2242, 1794. The most serious persecution took place Mount Ominc as "rainai shupao" (womb 2243, 2245-47 and 3330 in Oka Masahiko et in 1849, but it failed to eliminate the cult. See devotionalism). Quoted in Blacker, Catalpa Boa-, al., Edo Printed Books at Berkelev (TIokvo: ciYumani, fvashina, "Fdo shomin no Fuji shtnkc," 97, 2 12. See also James Sanfsird, "Win]d, NVaters, i99o). The information on Gesshin comes and Mivazaki, "Emperor Worship," 289. I Ni P R E S S 1I N S

- 39. COPYRIGHT INFORMATION TITLE: Making Mountains: Mini-Fujis, Edo Popular Religion and Hiroshige’s One SOURCE: Impressions no24 2002 PAGE(S): 25, 10-24, 26-47 WN: 0200109618008 The magazine publisher is the copyright holder of this articleand it is reproduced with permission. Further reproduction of this article in violation of the copyright is prohibited. Copyright 1982-2006 The H.W. Wilson Company. All rights reserved.